A lack of a skilled labor force puts new emphasis on the possible upside of a two-year community college degree

CLARK COUNTY — It’s a sunny afternoon, and inside the automotive tech building on the Clark College campus students are clustered around a Honda SUV. They’re trying to solve a problem with the power steering system. One thing you notice is a distinct lack of grease and grime. Instead most of the students are holding electronic devices or laptops as they diagnose the issue.

“This Accord, for instance, has probably 50 computers all in a network,” says Brian Tracy, the PACT Honda Automotive Program instructor. “They all have to talk to each other. Everything has to be perfect or it doesn’t work.”

Nearby a Lexus sits, with over 120 computers inside. Tracy says it drains the battery just sitting there. All of that means electrical education is not only the first, but the first and second thing automotive repair students at Clark learn.

“I’ve been in the industry 15 years,” says Tracy, “and I take offense to being called a mechanic. I’ve always been a technician, and that’s who I train — technicians.”

ClarkCountyToday.com recently visited Clark College to examine some of the many vocational and career programs offered by the college. The automotive technician course, for instance, takes two years and, through a partnership with Dick Hannah dealerships, its students are usually employed even before they finish the training. Some are getting paid before they even start school.

“Our goal is to teach the top 15 percent, and there’s where they’re going to enter the dealership at an entry level,” Tracy says. “They have a job day one. They have a job at the dealership before they ever come to our program, before I ever meet them they’ve already been at the dealership getting exposed to the industry.”

In the diesel shop next door big rigs sit, half dismantled, as students work together to understand what makes the massive machines tick. Their instructor, Chris Boucher, actually came to the school because he was having trouble finding qualified mechanics and technicians as a manager for Caterpillar.

“I was seeing about an 80 percent failure rate on hiring technicians,” he says, “not due to technical skills but due to soft skills — job 101 skills, tech 101… just being a good employee.”

He came to Clark College looking for recruits, and they sold him on coming there to fix the problem from the inside.

“25-30 years ago it was the grumpy, greasy mechanic in the corner of the shop. Everybody left ’em alone. Now you have to be very professional, really courteous,” says Boucher. “Companies are charging 130-140 dollars an hour for a technician, and that technician is the interface to the customer directly. They have to have customer service skills, sales skills, professional skills. And if we can’t build that, they’re not going to succeed in the job market.”

With Peterson-Caterpillar set to build a new repair yard along Lower River Road soon, Boucher says the demand for skilled diesel techs is likely to remain high. “If they become field mechanics, it’s not uncommon to be making six figures and have a furnished company vehicle, and tooling allowances, that kind of thing, not to mention benefits.”

That’s painting a pretty rosy picture for people willing to spend the two years it takes to get a degree in Clark’s automotive or diesel tech programs — and yet each instructor told us they always have plenty of space for more students.

“This is my second year. I’ve had 14 in both classes,” says Tracy, “We look for 20 for a full program in each side.”

National trend

It’s part of a national trend that’s been going on for decades now: Students go to high school, graduate, and head off to a four-year university. It’s become almost a coming-of-age ritual. Meanwhile vocational programs, like those at Clark College, have gained a reputation as being the place you go when you can’t hack it elsewhere.

“When I first thought of vocational schools it was more for like the people who get in trouble a lot, or can’t find regular jobs as they were,” says Kyle Cornelison, a student in the welding program at Clark. “You think of high school students who get in trouble a lot and can’t do anything else. But coming here I learned that the world wouldn’t run without people who do these trades.”

The end of the building boom, when the Great Recession hit a decade ago, further damaged the reputation of vocational schools, especially construction and manufacturing.

“We had this downturn where a lot of kid’s parents were laid off and as they’re kind of exploring what kind of career they want to go into they’re seeing bad things in the construction industry,” says Mike Bomar, former executive director at the Columbia River Economic Development Council, “long term (the construction industry) is a great, stable, long-time job with relatively consistent demand.”

As the economy recovered, and construction picked back up, the industry found that the workforce to support it has been slow to follow suit.

“I think a lot of kids growing up nowadays are more apt to do software development rather than pull apart a lawn mower or bicycle to give them that kind of mechanical aptitude,” says Caleb White, head of the welding program at Clark. “We’re still seeing them come in from a young age, but it’s at a slower rate and there’s a steeper learning curve.”

Training students for emerging sectors

While the construction and manufacturing industry still needs workers, many educational systems are now focused on training students for emerging sectors. In Vancouver, the STEM Network works with schools and the tech industry to ensure kids have access to emerging technologies in the fields of Science, Tech, Engineering and Math.

While those are the careers of the future, many good careers of the past aren’t going away. By some estimates, the United States will be short close to half a million welders by the end of the decade as a wave of retirements hit the industry. Things aren’t much better in the other trades offered on the Clark College campus.

Part of the problem is that, as school systems across the country tightened their budgets over recent years, CTE programs have been among the first to go. In many cases, students now have to go outside their high school campus to get hands on training for one of those careers.

Cascadia Tech Academy, formerly known as the Clark County Skill Center, allows students to engage in vocational training. But that means students from places like Battle Ground, Ridgefield, La Center and others have to travel well outside of their district to attend classes there. That often means sacrifices elsewhere, which means few kids will spend time dabbling in those things.

Even if districts do want to work with local employers to give students a chance to be exposed to construction or manufacturing jobs, through internships or apprentice programs, not all of them have the option.

“Let’s take just Hockinson for example, they don’t have a huge employer base in there,” says Bomar. “So if you’re trying to get an employer worksite experience, or a work-connected experience, they have to go outside of their district in many cases to build on that and do that effectively.”

That lack of exposure to those kinds of jobs at an earlier age is actually increasing costs for places like Clark College, according to Genevieve Howard, dean of workforce, Professional & Technical Education.

“A lot of students don’t know how to use a tape measure or hand tools,” she says. “They don’t understand how things work, they’ve never been given an opportunity to kind of take things apart.”

The bigger question then seems to be whether kids just don’t want to build things anymore, or whether they just haven’t had the chance to find that passion.

“What I like to see, and our focus is on, is how do employers and the education system, and parents and teachers, work together to really unlock those passions with kids?” says Bomar, who is now with the Port of Vancouver. “So they understand in a way that helps build their self-esteem, and aligns what they want to do, with what kind of opportunities are out there.”

Cornelison says his school didn’t have CTE classes, but he lucked into his love of building things.

“I took a drama class, but you had to build the sets,” he recalls. “So that was what really got me interested in doing stuff with my hands, like working on cars or building things.”

At the end of his two years at Clark, Cornelison expects to easily find long-term employment.

“There’s a ton of jobs out there for welders and fabricators, which they teach you both here,” says Cornelison, “One of the teachers told us here that you won’t find anything in the world that hasn’t been touched by a welder.”

Perception of blue collar workers changing

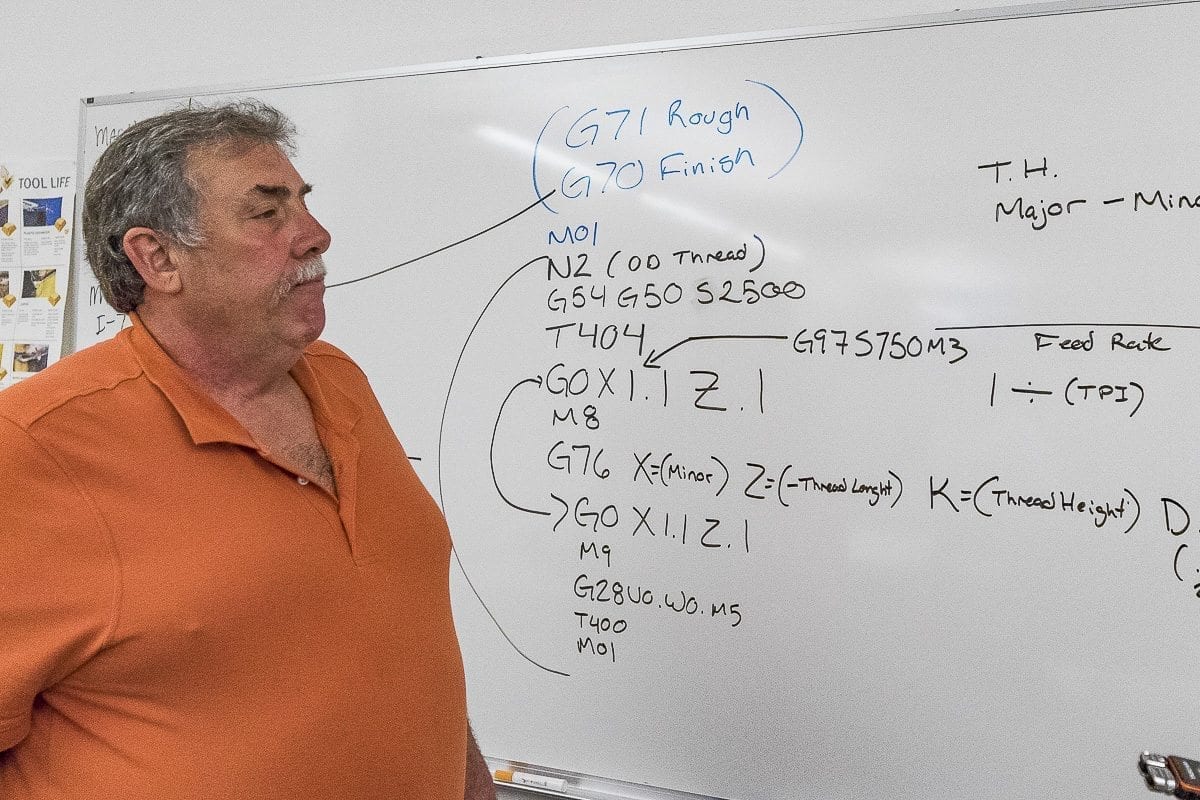

As for the perception that only slow learners end up in blue collar jobs, you should check out the mathematical formula on the whiteboard in Bruce Wells’ fabrication classroom.

“It is a place where a lot of guys come that aren’t good at academic stuff,” says Wells, head of the fabrication program. “They come in and use their hands, they’re hands-on people, craftsmen, I call them, that really take off in this kind of trade or situation. But we get a lot of engineer-type people who come in and really enjoy it.”

There are an estimated three million jobs in the U.S. that pay over $55,000, which don’t require a college diploma. Millions more living-wage jobs are accessible with a two-year degree from a program like the ones Clark College offers.

“The earnings potential for students is excellent,” says Boucher of his diesel technician students. “It’s also very mobile, so even in a depressed economy if you can work on a piece of heavy equipment in Vancouver, the construction business falls on its face here but it takes off in Iowa, you can probably move to Iowa and make about the same salary.”

The increasing lack of skilled craftsmen and a technical workforce has more employers working with schools. At Clark, Dick Hannah Honda provides vehicles and helps students with their tools, then hires many of them while they’re still finishing their education. Trucking companies have given the college a number of trucks and engines for their students to work on.

“Industry is what drives it,” says Boucher. “If they want to sculpt technicians for their product, then they have to get their product in here so we know how to work on it.”

It’s the kind of cooperation that Clark College hopes to foster more of. In the welding department, Caleb White says they’re hopeful employers will consider teaming up with the school.

“They are important, and we can get the students out to the workforce even quicker by doing that if they don’t want to do a traditional four year degree,” he says, “Because they can make a good living wage doing welding and fabrication.”

Program costs

On average, the cost of a two-year program at Clark College runs around $12,000. That’s a fraction of what you’ll spend at most four-year schools. Howard says that makes it a great choice for kids coming out of high school who aren’t sure what they want to do, or people considering a change of career.

“There are a lot of options. Specifically at Clark College we have around 100-plus degrees that are available for students to choose,” she says. “Going to a community college doesn’t doom you into never going to a four-year college, but it does provide exposure to many more options.”

Of course there’s far more than automotive or diesel technician, welding, or fabrication. You can study computer technology, programming, nursing, and much, much more.

But that still leaves the obstacle of changing perspectives, not only of students, but the adults around them.

“If parents and teachers and counselors aren’t showing them these as valid pathways and valid opportunities to explore, they never get the chance to make that decision until it’s too late,” says Bomar. “Until they’re already down a certain pathway that may not be consistent with what they want to do or what would be most rewarding for them, both financially and from a life experience standpoint.”

Bomar says that, while acknowledging that even he struggles with the idea of his own kids going to a two-year school.

“I have three young kids, and my initial thought is they’re going to college, right, and not thinking about trade school stuff,” he admits. “And I’m somebody who’s steeped in what those opportunities are and what the rewards are of technical education.”

One key to addressing that will be continued communication between the industries needing to fill jobs, and the educational system tasked with making sure they’re preparing students for their best possible future.

“Education partners think employers just simply want to crank out widget employees that they can put to work right away and make money off of,” says Bomar. “And, employers think education just simply wants to get their resources and have them spend a lot of time for kids that they aren’t necessarily going to be able to utilize later on.”

Perhaps the rising cost of tuition at many universities will end up being the ultimate factor in pushing young people to look elsewhere. And maybe those teens pushing back against their parents will force them to look into what other options might exist to be sure their offspring don’t end up back on the couch and unemployed after spending tens of thousands of dollars on higher education.

“I think Clark provides a great place for students, either right out of high school or returning students, to kind of come in and figure out what it is that interests them,” says Howard. “Specifically with career and technical education, it’s really demystifying what these programs are, and the careers that are attached to them. They’re much better careers than I think people assume.”

Also read:

New website helps connect employers and career seekers