Caleb Jones credits his parents and baseball for helping him thrive

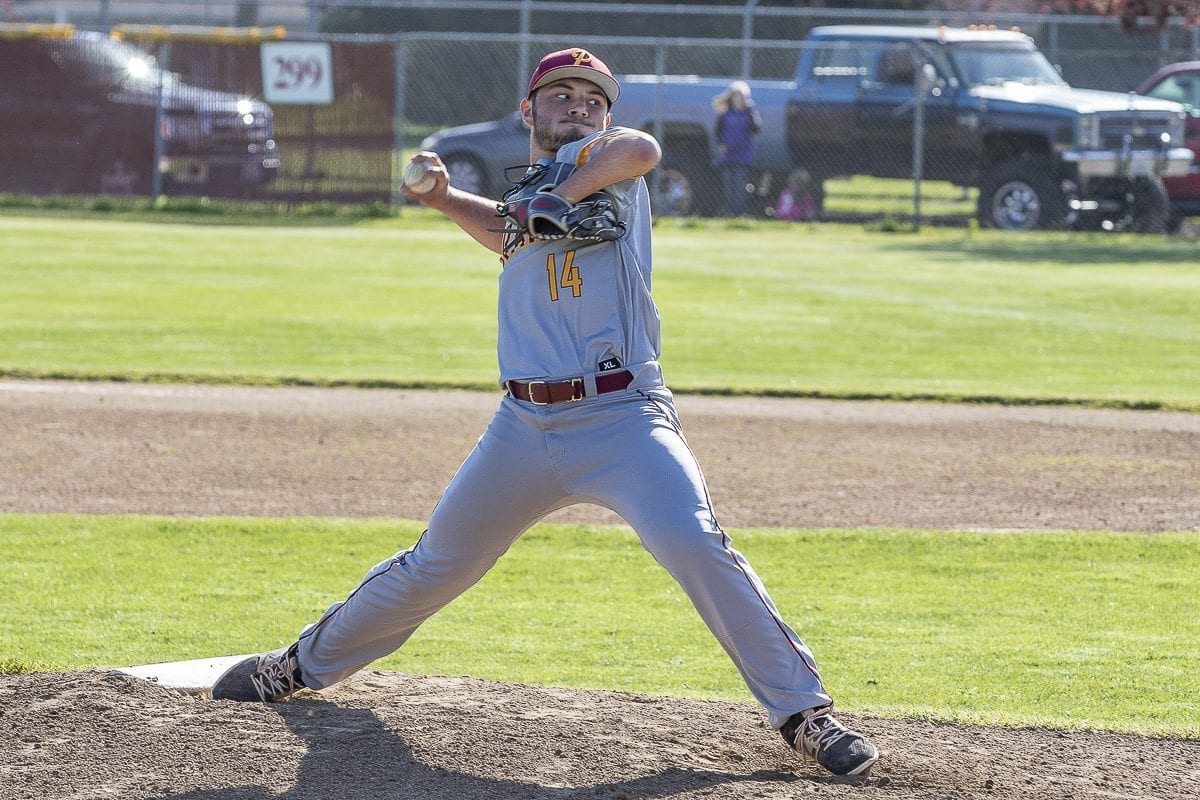

BRUSH PRAIRIE — Caleb Jones is so smooth going from pitcher to fielder that it does not appear at first glance there is anything different about him when he is on the mound.

He is simply a varsity pitcher for the Prairie Falcons.

That, he says, is one of the greatest accomplishments of his life. And there are times he wishes he could be just that, a high school pitcher.

He knows he is different, though. He knows his delivery to the plate is not the norm.

Take a closer look.

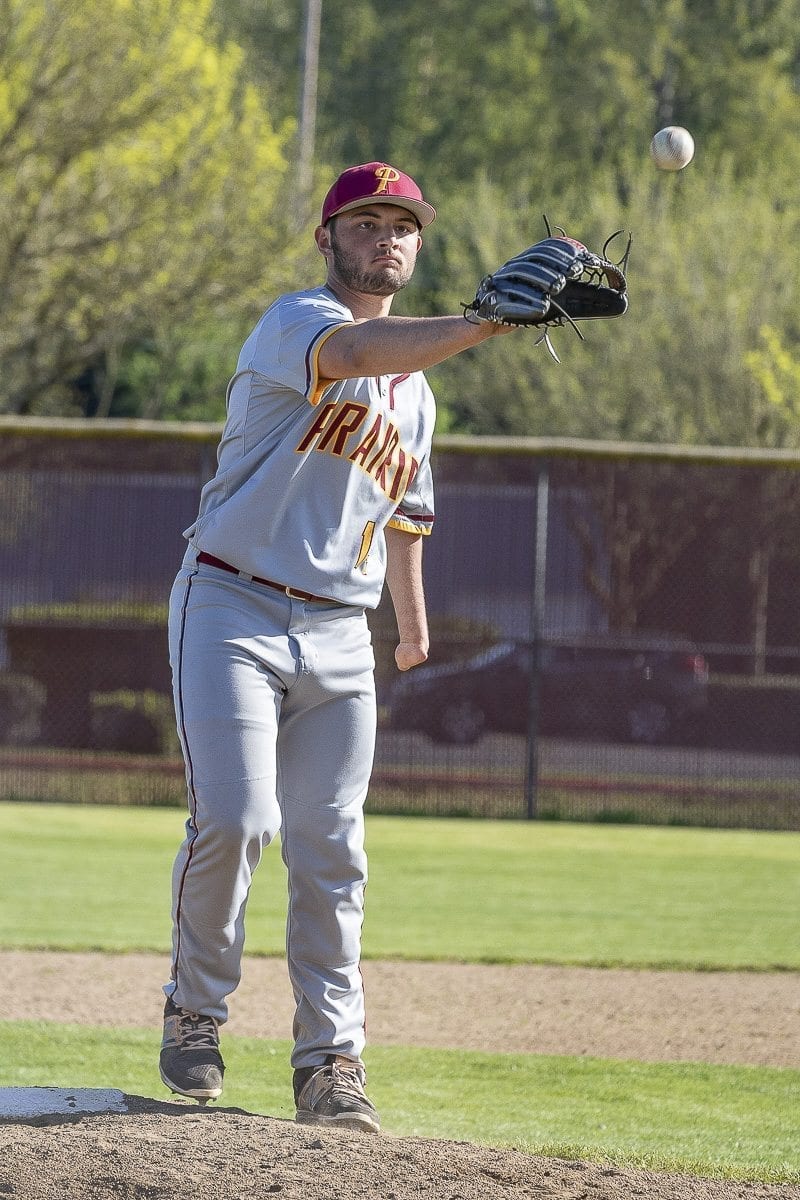

There is Caleb Jones, pinning his glove to his body using his left arm and wrist. He grips the baseball with his right hand and his accurate right arm delivers a strike. In the same motion, he slips his glove on his right hand.

Caleb Jones is not just a high school pitcher. He is a one-handed pitcher.

Years of training and his talent have led him to the varsity level. Now a junior at Prairie, he also has learned to accept his condition, to embrace it, and he wants to inspire other “limb-different” athletes.

The cruel taunts from some children and the ignorant statements from others used to take a toll on Jones. That is all in the past.

He was born with one hand. He cannot do anything about that. He can make the best of it and help others like him to do the same.

“Just don’t give up. It’s going to be hard, thinking you are out of place,” he said. “Keep pursuing your dream. It will get you to great places. When you get to your dream, it’s an amazing feeling.”

Jones likes to share the credit. His father Chad has been instrumental in helping him prepare for life on and off the baseball field, coming up with better ways to field a ball and better ways to cut a steak, for example. His mother Sarah has been the emotional support, especially during the bad times.

Of course, baseball was another big help in Caleb’s development.

“I first fell in love with baseball when I realized I could do it just like other people,” Jones said. “When I was little, I didn’t think I could. I looked at everybody, ‘Oh, I don’t think I can do that.’ But when I was right up to speed with everyone else, it made me feel like this is my sport.”

Jones made the most of his one hand by learning to throw at an early age. Not just a baseball. Anything. Sarah said she was hit in the head more than once from her young son in the backseat of the car as she was driving.

“Books, cups, anything he could get his hand on, he would throw it,” Chad recalled.

Chad’s son was accurate, too. By the time Caleb was in Little League, he was too strong. He was not allowed to pitch one season because he was so overpowering.

“Throwing just came naturally to me,” Caleb said. “Over time, I figured out how to do my own thing.”

When he was 6 years old, Caleb met Jim Abbott, the one-handed pitcher who threw a no-hitter in the major leagues. They played catch. Abbott praised Caleb’s transfer move then, the ability to catch a ball, transfer the glove to his body and get the ball in his hand to in a ready position to make a throw. Since then, it has improved.

Caleb again credits his dad for coming up with a training plan. Caleb would take tennis balls and throw them up against a wall and practice fielding the balls as they bounced back toward him.

“Sometimes two or three times a day, every week,” Caleb recalled. “My transfer just got faster and faster.”

On the baseball field, he felt pretty much an equal. But not always at school. There were mean children, those who used words to intentionally hurt. Plus there were several children who just did not know any better who would say things that cut deep.

Sarah Jones was always there with the right thing to say, Caleb said.

“If I started to get discouraged about things, she would have conversations with me,” Caleb said. “She would remind me I can be just like everyone else, I am like everyone else. She helped me through the rough times, keeping me going, I guess.”

Today, Sarah calls it “nerve-racking” to watch her son pitch but not because he has one hand, not because he is different. It just makes one nervous to watch a loved one in athletics.

“He has come a long ways. He grew into himself,” Sarah said. “He has figured out … you get the same opportunities. You have up to prove yourself, like anybody else.”

It was difficult on everybody at times. An ultrasound when Sarah was pregnant revealed a problem.

While they are not 100 percent certain, his parents believe that Caleb suffered from amniotic band syndrome, which occurs when an unborn baby gets entangled in the “fibrous, stringlike amniotic bands of the amniotic sac,” according to Shriners Hospital for Children. The restriction of blood flow can stop the normal growth of a limb.

Sarah and Chad had their moments of fear and anguish. Soon enough, they came up with a philosophy: “Let’s figure it out.”

Another rallying call: “He can still play baseball.”

Chad knew of Jim Abbott, who threw a no-hitter for the New York Yankees in 1993. Chad also grew up playing baseball against former Battle Ground standout DaWuan Miller, a one-handed athlete who played football at Boise State.

Sure enough, Caleb, even without a left hand, was “blessed with natural talent,” Chad said. (While Caleb is known more for pitching, he also is a switch hitter. He can wrap his “nub,” as he calls it, around the bat for a bit more control.)

Still, years later, it was a big deal for Caleb when he made varsity.

“Being able to fully realize you are good enough,” Jones said. “I look back on everything that I went through and all the work I put in, it was very satisfying.”

Even after making it to varsity, he still had deliver as a ball player. In seven appearances for the Falcons this season, he has 21 strikeouts in 19 innings pitched while giving up four earned runs.

“I’m very proud of where I am right now,” Jones said. “Everyone has to put work into baseball. I’ve had to put in a little bit more.”

He also is satisfied with where he is in life. Elementary school was tough. It got a bit easier in middle school, but he was still self-conscious.

As a high schooler, he knows exactly who he is — a teenager trying to excel in everyday life.

Today, he jokes about his nub, even tells people he lost his hand to a shark attack.

“Everybody has something in their life that is different than anyone else,” Jones said.

Embrace it.

As a youngster, he tried to ignore anyone who had questions about his limb. These days, he is enthusiastic about the conversations, almost like talking about it is therapeutic.

He still get flummoxed, though, when people ask him if he would prefer to have two hands.

“I don’t know how to answer that because I’m living my life with one one hand,” Caleb Jones said. “I don’t know what it would be like.”

In athletics, he just knows he is a baseball player, a baseball player who happens to have one hand.