VANCOUVER — Inside a sunny weight room at the Washington State School for the Blind, a young woman named Klaira dips her torso over a 100-pound weight. Feeling for the rough part of the bar, she positions her left hand under, right hand over the weight.

“Push power through your legs, Klaira,” her coach, Judy Koch-Smith, advises. “That’s right. One hand over. One hand under. Hands close together. Butt down. Head up.”

The 17-year-old straightens her back, brings her head up to gaze forward and deadlifts the weight. Her classmates, all students at the Vancouver-based state school for blind youth — all members of the school’s award-winning powerlifting team — clap when they hear Klaira’s “umph” as she lifts the heavy weight off the floor, then raise their voices in a chorus of support.

“Yeah, Klaira.”

“You got it.”

“Good job.”

This type of supportive encouragement doesn’t stop inside the school’s weight room, says Steve Lowry. Along with Koch-Smith, Lowry coaches the team of young powerlifters.

“I’ve coached other sports before, but this is different,” Lowry says. “Everyone in the powerlifting community is incredibly supportive of each other. When we go to meets, they’re not competing against each other, they’re competing against themselves.”

Lowry says the sport brings people of all ages, sexes, shapes, sizes and abilities together.

“There are people as young as middle-schoolers competing with people in their 80s,” Lowry says. “And you may have someone lifting 100 pounds, and someone else lifting 400 pounds. It’s a huge range of abilities at the competitions.”

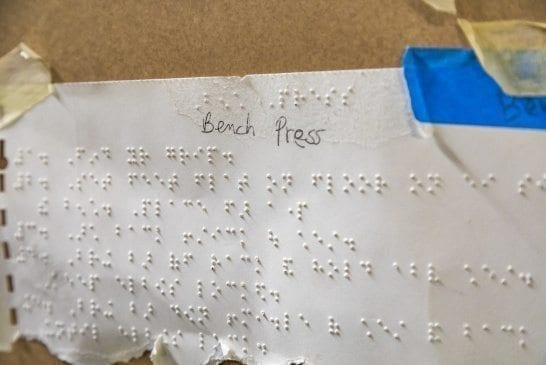

Having broken several state and regional records already this year, the group of seven high-school-aged powerlifters found themselves on the world stage in mid-November, competing at the World Association of Bench Pressers and Deadlifters’ World Championships in Las Vegas.

They returned to the Washington State School for the Blind with some pretty legitimate bragging rights — Alexis Payne, 18, set a world record for bench press in her weight class/age group; Justin Naramor, 19, and Alex Johnson, 16, set world records for deadlifts in their weight class/age group; 15-year-old Husai Sanchez set two world records, in deadlift and bench press, for his weight class/age group; and Klaira Perez, 17, Cheyann Purjeu, 15, and Damian Parra, 14, all set new personal bests in their deadlift events.

Three weeks after competing at the World Championships, the students were still feeling the thrill of bringing home first- and second-place medals, setting world records and, of course, experiencing Vegas firsthand.

“This was everyone’s first time at the World Championships,” Lowry said. “And they were competing in this big auditorium full of people … they really rose to the challenge.”

When you ask the teens about what powerlifting brings to their lives, they’ll tell you they feel stronger, more confident and encouraged to strive for their own definition of “best” when they’re powerlifting. Some students found the sport through friends, or because one of the coaches encouraged them to try it.

Klaira Perez says she found powerlifting after trying goalball, a sport designed for blind athletes in which players throw or roll balls with bells inside them toward their opponents’ end of the court and opposing players use their own bodies, often by lying on the floor and stretching their arms above their heads, to block the flying balls.

“Not being able to see the ball, listening for it … I would panic. It was terrifying,” Perez says with a dry sense of humor that makes her peers break into laughter. “So I wanted to try something different.”

For Husai Sanchez, the 15-year-old who broke two world records at the World Championship competition last month, the journey toward powerlifting wasn’t exactly a natural fit.

“When I came here, in 2012, I heard about powerlifting and I was confused,” Sanchez says. “I thought maybe you had to lift yourself with your own body!”

Once he realized what powerlifting really entailed, Sanchez joined the team in 2013 and hasn’t regretted his decision.

“The sport itself has had a huge influence on me and has brought me things I’d never imagined,” Sanchez says.

Koch-Smith has coached powerlifters at the School for the Blind for the past 10 years and says the sport has unique advantages for visually impaired or blind students: For starters, the athletes don’t have to rely on sight to learn the proper body postures and techniques for doing deadlifts and bench presses. Instead, they can count on auditory cues and their body’s own muscle memory during competitions. And, says Koch-Smith, the sport can help the students increase their own body awareness.

“Weightlifting can be very helpful for students … [to gain] a better understanding of concepts related to movement: up/down, left/right, forward/back, etc.,”

Koch-Smith says. “As you may guess, for students who have been blind since birth, they often have ‘gaps’ in learning about and understanding relative space unless they have ‘hands on’ instruction for some of these concepts.”

What’s more, adds Lowry, who has been coaching the powerlifters at the School for the Blind for the past seven years, the sport encourages each athlete to strive for their own personal best without having to tear other competitors down to “win.”

“The only sport I’ve seen that comes close is probably roller derby. That’s another sort of alternative sport where the competitors are competing, but are still very supportive of each other,” Lowry says. “In powerlifting, it’s so cool for these high-schoolers to be competing with their sighted peers and to know that everyone is encouraging each other. It’s almost like all of the lifters are on one giant team.”

Click photos below to view slideshow: