Todd Myers of the Washington Policy Center offers examples of areas state officials have failed in their response to the pandemic

Todd Myers

Washington Policy Center

Two years into the COVID pandemic, the people of Washington are still seeing some of the same failures from government officials that occurred in the first year.

The recent shortages of test kits is one high-profile example. A starker, but less obvious, example is the failure of state officials to live up to their promises to contain COVID using contact tracing.

In the state’s contact tracing program, staff from the Washington State Department of Health (DOH) attempt to contact people who have tested positive for COVID. Staff provide patients with information and help determine who they have been near in the past few days. It is voluntary and people are not required to respond, but those I have spoken with who received a call say it was helpful.

But very few people are receiving the calls.

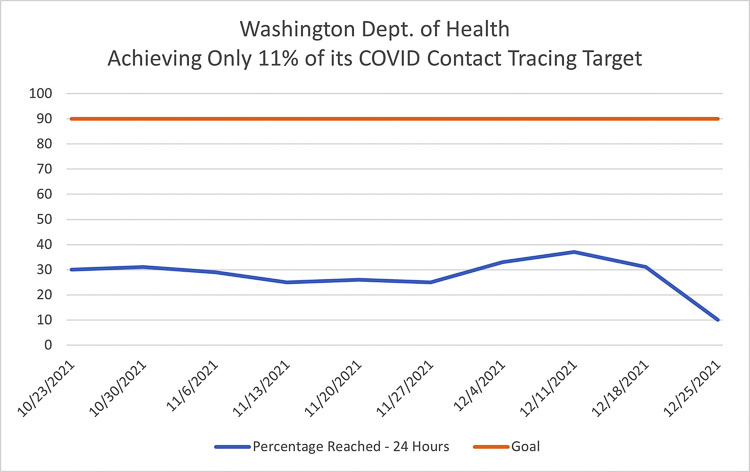

Since the contact tracing program began in 2020, DOH has a goal of reaching 90% of COVID-positive patients within 24 hours. DOH says, “These targets represent our long-term goals and we expect to see improvement over time as we refine our processes for successfully contacting people.”

More than a year later, there has been little, if any, improvement. Indeed, at the moments when effective contact tracing has been most important – in the middle of outbreaks – the program has essentially collapsed.

The most recent outbreak is a good example. As the number of COVID cases increased across the state, the percentage of people contacted by DOH in the first 24 hours fell from an already paltry level of about 35% to just 10%. This is just 11% of DOH’s self-imposed target of reaching 90% of COVID patients.

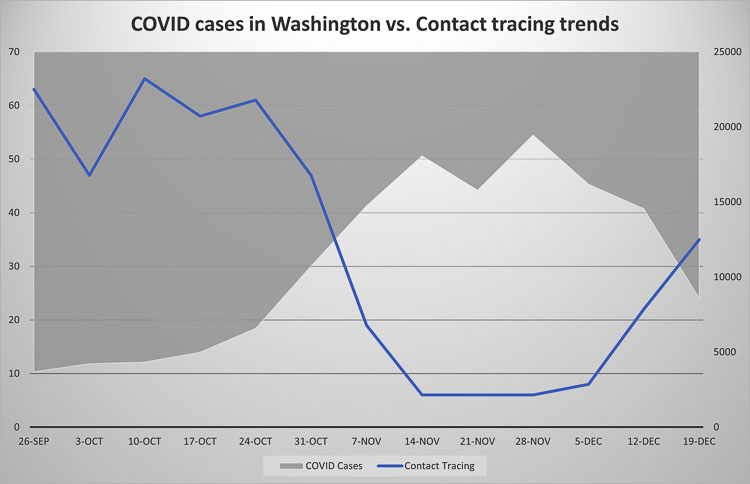

Part of the decline was due to a significant increase in the number of cases assigned to the DOH. It increased from 4,318 for the week ending December 18, to 12,574 for the week leading up to Christmas.

That doesn’t tell the whole story. Incredibly, DOH actually made about 100 fewer contact attempts in the week before Christmas, precisely at the time they should have been ramping up.

Additionally, the failure to reach the goal isn’t because people simply refused to respond. DOH only attempted to reach 18 percent of people who tested positive, ultimately contacting about half of them. Even if everyone had responded immediately, DOH would have still been far short of its goal.

This is the second year in a row DOH has failed badly to adjust to an increase in cases.

In 2020, when cases increased, DOH’s contact rate fell from about 60% all the way down to just 6 percent in less than a month.

As with 2021, the collapse came at precisely the moment when the state needed to improve its effort. As cases increased, the state’s contact tracing program fell apart. The contact rate increased only once the wave of cases had passed, when it was less important.

The fact that the same pattern has appeared two years in a row is evidence that the administration did not learn from its poor performance last winter. State leaders did not anticipate the wave of cases associated with the omicron variant, despite significant publicity that it was coming to the United States. Once the highly transmissible variant was here, the governor and agency leaders did not take the necessary steps to address the threat, reducing the number of contacts precisely when they should have been increasing.

This isn’t the only circumstance where state officials have failed to anticipate or adjust to the challenges of COVID. However, it is stark evidence that in the moments when government officials require us to rely on them most, they haven’t been up to the task.

Todd Myers is the director of the Center for the Environment at the Washington Policy Center.