Todd Myers of the Washington Policy Center takes a close look at the actual performance of state efforts during the pandemic

Todd Myers

Washington Policy Center

As Washington state removes masking mandates and moves closer to a post-pandemic situation, politicians are taking credit for saving lives, claiming their actions prevented more deaths.

Assessing those claims by taking a close look at the actual performance of state efforts during the pandemic is important for a few reasons. First, it provides basic accountability that is critical to good governance. Second, it provides guidance about what works and what doesn’t for future health emergencies. Finally, it provides a good general sense of whether government agencies are up to the task of providing health services when it is critical. A close look at one of the state’s COVID-19 programs tells a very different story. Indeed, Department of Health (DOH) officials now admit that the best approach is to empower individuals to care for themselves and others around them.

The almost total failure of the state’s COVID-19 “contact tracing” (a program to help COVID-19-positive patients contact those they might have infected), their subsequent inability to acknowledge the failure, and then inventing excuses for the failure, is a stern warning about the dangers of relying on government agencies to provide health care. This was on display at the DOH’s recent media briefing.

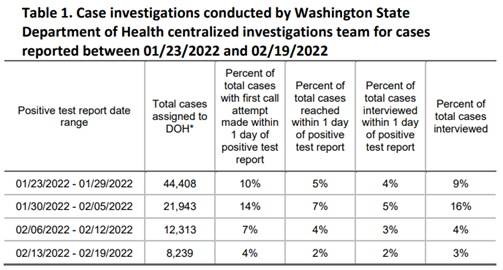

Since it was launched, the state’s contact tracing effort has failed badly to meet its own goals. It may be that the aggressive contact tracing goal set by DOH was never achievable, which itself says something about the politics of health goals. Either way, two reporters asked about the agency’s data showing they are falling far short of their target.

Claudia Yaw of the Everett Herald asked, “It is my understanding that the state had this initial goal to contact the vast majority of infections, and only a tiny fraction of that is being met. I’m just wondering if this is concerning to you all, and if it was a result of the state just being overwhelmed by cases.”

Dr. Tao Sheng Kwan-Gett, the Chief Science Officer at DOH, responded that “the omicron variant really made us realize the limits of contact tracing. The omicron variant was so transmissible, and so quickly transmissible that it really stretched the limits of our ability to respond with contact tracing.” This is not accurate.

DOH’s contact tracing program was failing long before omicron became prevalent. In the winter of 2020, when the delta variant was still predominant, DOH was only reaching 6 percent of people who tested positive for COVID-19 in 24 hours, as compared to the agency’s goal of reaching 90 percent. DOH never came close to reaching their target at any point in the program’s history – before or after the omicron variant.

Additionally, as the number of COVID-19 cases has declined in recent weeks, the percentage of people reached by contact tracing has fallen even more rapidly. The most recent report indicates they reached only 2 percent of people who tested positive. Two percent.

The program, which DOH indicated was an important part of its effort to contain the coronavirus, simply failed. Rather than trying to divert blame, DOH should acknowledge the failure so policymakers and the public can learn from it. Otherwise, we will continue to throw taxpayer money away on a program that doesn’t work.

That effort to avoid accountability also led to an interesting admission by DOH director Dr. Umair Shah.

Reporter Kate Walters of KUOW radio asked, “How do you think the state is doing on that front considering the really small percentage of people who are being contacted at this point.”

Dr. Shah provided a long answer that completely avoided the causes of DOH’s failure and didn’t acknowledge that the targets had been badly missed. I have transcribed his entire answer below so you can read it for yourself.

Later, Dr. Shah added this notable comment: “As we get more and more tools out to people that we will then have to be really relying on those individuals to take actions that are going to be protected for themselves and those around them.” While failing to admit DOH’s program was completely unsuccessful, he implies the responsibility for protecting others falls on individuals.

This is exactly the argument many who have been critical of the state’s extremely restrictive approach to vaccine mandates and masking have been making for some time. Give people the tools – vaccines, testing, masks, etc. – and let them find the best ways to protect themselves and their families.

Up to this point, the governor and DOH have argued that, literally, only the government can protect people from COVID-19. Faced with accountability for their own failure to protect people with the contact tracing program, they now admit that individuals are best able to make health decisions.

This is why accountability is important. When faced with the reality of the failure of the program, politicians are forced to admit – albeit circuitously – the truth of the situation and acknowledge that people should have the freedom and responsibility of making their health decisions. That may not have been the takeaway message Dr. Shah intended, but it is the truth and offers an important lesson for how the state should address future health care policy.

Kate Walters, KUOW: “How do you think the state is doing on that front considering the really small percentage of people who are being contacted at this point.”

Dr. Shah: “A couple of things, that, first of all, that, contact tracing has been an effective tool in a number of different disease activities globally and domestically. And in particular it has been used in other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and other areas where it really does look like you have an ability to know someone who has been infected, the people that they have been in contact with, and in a very quickened pace able to make contact with those individuals and essentially protect others, so that you interrupt transmission. So, that’s the concept Kate, as I am sure you’re aware. With that in mind though you have to remember that contact tracing is a part of an entire system and it starts with somebody who has a symptom or somebody‘s been exposed and they have a test that comes back positive. So, that implies awareness and implies testing. And as I’ve said before you can’t trace without a case so once you have a test that is positive now that individual becomes a case and that when that individual becomes a case then we do case investigation. So, we have to then interview and talk to that person to be able to really move forward with what we’re trying to do to protect that individual and because we’re taking a population health perspective it’s not just that individual but it’s the population as a whole. And then on top of that, that’s where contact tracing comes in. Any of the contacts with that individual has and how do we move forward with making contact with those individuals. Now, the one thing that I would say about the state of Washington, and we should all be proud of is our WA Notify, our real technology tool that we have used and utilized so it has lessened the human interaction need where we have somebody, and we’ve got a lot of people, especially during Omicron that were telling us that they had gotten an alert on their phone and it said that look you may have been exposed at that point that individual has some information that allows them to determine what that exposure is, what they’re concerned for risk is, and to get tested and further if they have symptoms to isolate away from others. So, there’s a lot that goes into this and we’re really hoping that for the future that we can continue to focus on not just the human aspect of it, which is always the critical piece, but the technology aspect which will also allow for that work to be done. So, I think in the future is really contact tracing is there, but I would say that one thing that’s really important as we move forward, both in case investigation and contact tracing, as we’re looking at focus populations where we are very concerned about maybe either vulnerability because of some other medical condition, or outbreaks, or age, or certain congregate settings. That’s really an area of focus, and then certainly doing everything we can from that to be able to make sure that we are helping interrupt that transmission or furthering a bad outbreak. So, that’s really where the focus is going to be more and more, where it’s more empowerment of people so they have information of what they can do individually while we’re also focusing more on those most vulnerable and/or those that are part of the outbreak. So, that’s really, I think, where we’re going in and using technologies along the way.”

Todd Myers is the director of the Center for the Environment at the Washington Policy Center.