Jason Mercier of the Washington Policy Center states, ‘state and local government employment contracts should not be negotiated in secret’

Jason Mercier

Washington Policy Center

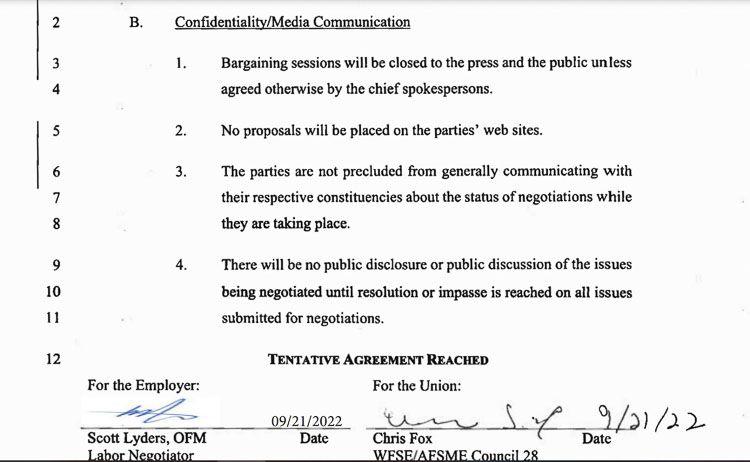

Unless the legislature decides to step in and require transparency for state government employee compensation talks, they will continue to be conducted in secret based on an agreement the Governor’s office recently reached with union officials. Section 39.13 of the tentative 2023-25 contract for state government employees maintains secrecy for future compensation negotiations. Under the heading “Confidentiality/Media Communication” the new contract says (page 176 of pdf):

- “Bargaining sessions will be closed to the press and the public unless agreed otherwise by the chief spokespersons.

- No proposals will be placed on the parties’ web sites.

- The parties are not precluded from generally communicating with their respective constituencies about the status of negotiations while they are taking place.

- There will be no public disclosure or public discussion of the issues being negotiated until resolution or impasse is reached on all issues submitted for negotiations.”

In response to public concerns about this type of secrecy the Governor’s office says that “the bargaining process has been consistent across administrations.”

Missing in this statement is the context that the changes made in 2002 by the legislature to allow the Governor to make these decision does not require secrecy. That is a choice evident by agreeing to terms like those in Section 39.13.

Before 2002, collective bargaining for state government employees was limited to non-economic issues such as work conditions, while salary and benefit levels were determined through the normal budget process in the legislature.

Since the collective bargaining law went into full effect in 2004, union executives no longer have their priorities weighed equally with every other special interest during the legislative budget debate. Instead, they now negotiate directly with the Governor in secret, while lawmakers only have the opportunity to say “yes” or “no” to the entire contract agreed to with the Governor. Not only are there serious transparency concerns with this arrangement, but there are also potential constitutional flaws by unduly restricting the legislature’s constitutional authority to write the state budget.

The decision made in 2002 that limited the authority of lawmakers to set priorities within the budget on state employee compensation should be reversed. This is especially important considering the compelling arguments made in the University of Washington Law Review, noting the 2002 law is an unconstitutional infringement on the legislature’s authority to make budget decisions.

Ultimately, state employee union contracts negotiated solely with the Governor should be limited to non-economic issues, like working conditions. Anything requiring an appropriation (especially new spending that may rely on a tax increase) should be part of the normal open and public budget process in the legislature. This safeguard is especially important when public sector unions are also political allies of the sitting Governor.

If the legislature is going to continue to allow the Governor to set the terms for these budget decisions totaling hundreds of millions of dollars, these contract negotiations should be subject to the state’s Open Public Meetings Act (OPMA) or at a minimum, utilize a process like the one used by the City of Costa Mesa in California to keep the public informed.

That process is called COIN (Civic Openness in Negotiations). Under this system, all of the proposals and documents that are to be discussed in secret negotiations are made publicly available before and after meetings between the negotiating parties, with fiscal analysis provided showing the costs.

While not full-fledged open meetings, providing access to all of the documents before meetings would inform the public about the promises and trade-offs being proposed with their tax dollars before an agreement is reached. This would also help make it clear whether one side or the other is being unreasonable, and would quickly reveal whether anyone, whether union executive or state official, is acting in bad faith.

For example, a week before union officials announced a deal had been struck with the Governor’s office they used these terms to describe the status of the secret talks to their members: “Dangerous.” “Hazardous.” “Lowball compensation.” “Disrespectful.” “Unsafe.” “Public services are at risk.”

A few days later the union’s tone changed instead to bragging about the secret talks yielding the “largest compensation package” in history.

State and local government employment contracts should not be negotiated in secret. The public provides money for these agreements. Taxpayers should be allowed to follow the process and hold government officials accountable for the spending decisions that public officials make on their behalf.

As for the taxpayer costs for the 2023-25 secretly negotiated contract, OFM estimates that information will be posted on its website on Oct. 3.

Jason Mercier is the director of the Center for Government Reform at the Washington Policy Center.

Also read:

- POLL: Why did voters reject all three tax proposals in the April 22 special election?Clark County voters rejected all three tax measures on the April 22 special election ballot, prompting questions about trust, affordability, and communication.

- Opinion: The war on parental rightsNancy Churchill argues that Olympia lawmakers are undermining voter-approved parental rights by rewriting key legislation and silencing dissent.

- Opinion: An Earth Day Lesson – Last year’s biggest environmental victories came from free marketsTodd Myers argues that Earth Day should highlight free-market solutions and grassroots innovation as more effective tools for environmental stewardship than top-down mandates.

- Opinion: Time to limit emergency clauses and give voters a choiceTodd Myers urges the governor to remove emergency clauses from bills that appear intended to block voter input rather than address real emergencies.

- Letter: C-TRAN Board improper meeting conductCamas resident Rick Vermeers criticizes the C-TRAN Board for misusing parliamentary procedure during a controversial vote on light rail.