Removing one “stop light” on the interstate while creating another on the Columbia River

“The proposed Columbia River Crossing has turned into a high-stakes limbo dance: How low can the bridge go? This was the opening to a local news story a decade ago. Is the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) program about to follow in those same footsteps?

John Rudi runs Thompson Metal Fab (TMF) in Vancouver and his company builds products from steel and metal which are shipped all over the world. The tallest TMF projects have exceeded 165 feet. TMF was one of three firms requiring millions of taxpayer dollars in “mitigation” in the failed Columbia River Crossing (CRC) effort.

In creating the current project, Governors Jay Insee and Kate Brown signed a memorandum, part of which directed a thorough review of the previous Columbia River Crossing (CRC) files and information. The bridge is “the only stop light between Mexico and Canada on the I-5 corridor,” said Washington Gov. Jay Inslee. Will the IBR create a different stop light, this one on the Columbia River?

The supposed intent of the memorandum was to learn from the past and use what they could in creating a new bridge. Did the IBR team members learn from the past, or are they going to repeat some of the same mistakes?

The US Coast Guard (USCG) is asking for public comment on an IBR proposal. It has received a Preliminary Navigation Clearance Determination from the IBR team on a bridge that will provide 116 feet of clearance for marine traffic. To many citizens, this is reminiscent of “the bridge too low” moniker that plagued the failed CRC effort a decade ago.

Last week, the Coast Guard indicated ODOT and WSDOT are leading the effort and submitted a request which begins a long process for approval. In the previous effort, there were several failed efforts to obtain a navigation permit from the Coast Guard at a 95- and 110-foot clearance. In November 2020 the IBR team was told it would need to obtain a new permit.

“This Public Notice (PN) is soliciting for comments exclusively related to navigation. Maritime transportation system stakeholders (vessels and facilities) are highly encouraged to carefully review this notice and provide comments with regard to the proposed bridge’s ability to meet the needs of navigation to include mariner requirements for horizontal navigation clearances and vertical navigation clearances,”

In the previous effort, the request was denied because the CRC project team failed to provide documentation showing the 95-foot clearance “will meet reasonable navigation requirements” according to a December 2011 letter. The CRC later tried with 110 foot clearance. The Coast Guard was not able to approve the bridge permit application. They said they may require the project to supplement the Federal Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) in order to accept an application. They ultimately got approval for a structure with 116 feet of clearance.

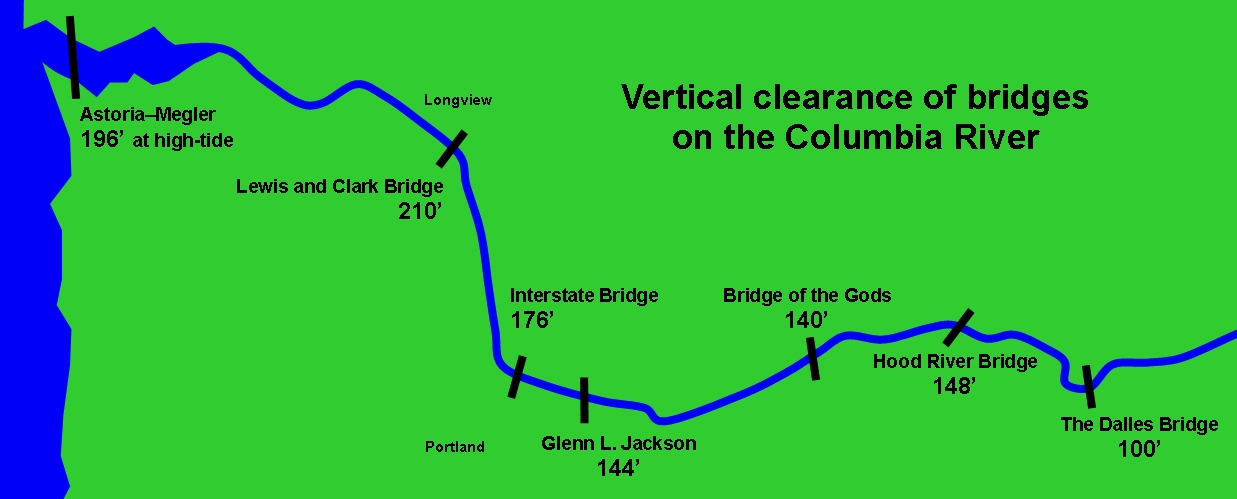

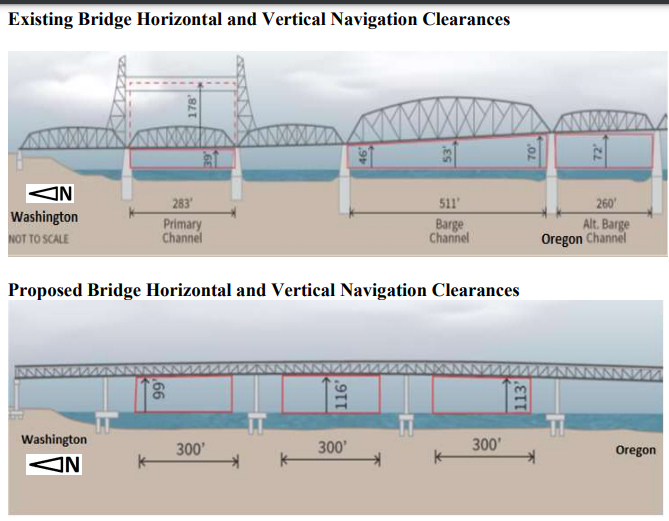

The existing I-5 bridge provides roughly 70 feet of clearance at the tallest section. But that depends on Columbia River water levels. When fully open, the lift span rises to about 178 feet. In comparison, the I-205 bridge is 144 feet tall over the wide center area of the bridge.

The bridge across the river at Longview has 210 feet of clearance. In Astoria, the bridge provides 196 feet of clearance. To the east, the Bridge of the Gods provides 140 feet of clearance. It would seem to raise the question, why would the IBR build a different kind of “stop light” for marine traffic on the Columbia River with a 116 foot bridge?

At the heart of the previous “bridge too low” dispute were three up-river manufacturers. A 2006 public hearing on the proposed CRC project included testimony from companies who utilize the current bridge lift, including Thompson Metal Fab.

“I know it was reported in the past that Thompson Metal Fab needed 125-foot clearance, but that is not accurate,” Rudi said. “Our tallest loads have been 165 feet with many over the 125-150 foot range.” He also noted that the USCG recommends a clearance buffer of no less than 10 feet.

In 2011, TMF built a structure for Parker Drilling. It required over 165 feet of clearance. Rudi noted that his firm sometimes will need a bridge lift three to four times a year, and other years none.

“The important point to understand is that the large projects that require high clearance take months or a couple of years to complete and there are hundreds of thousands of man hours that go into them,” Rudi said. “A big benefit to our local economy. It’s not really a frequency issue as much as it is a capability need.”

Every eight to 10 years, the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) dredge cleans out the Columbia River basin in the area according to one report. Last year, roughly 50 days were spent dredging over 2 million cubic yards of silt and dirt from the main shipping channel according to one report.

The same dredge equipment is still being used as during the CRC debate. The USAV Essayons is the dredging vessel with the highest air draft, according to Tom Conning, Public Affairs specialist for USACE, “measuring from the keel to top of mast is 126 feet; however, the maximum air draft is 104 feet. Our team didn’t know if there was a particular requirement from the USCG regarding buffer requirement.”

One of the other vessels, the Yaquina, does work from Vancouver to The Dalles on an annual basis. Its maximum air draft is 92 feet.

“Some of these waterway users are major businesses that provide a lot of jobs,” said Capt. Mark McCadden a decade ago. He was chief of external affairs for the Coast Guard in Seattle. “The corps has a dredge that won’t clear 95 feet. Think about if we had another Mount St. Helens, with silt dumping into the river, and the dredge couldn’t get under that bridge.”

A mid-level bridge (with 95-to-110-foot clearance) has “a low probability of meeting the reasonable needs of navigation or of obtaining a Coast Guard permit,” wrote D.A. Goward, the Coast Guard’s marine transportation director back then.

“Our needs for navigation clearance have not changed since the original survey by CRC,” Rudi told Clark County Today. “Obviously, a static bridge that meets the needs of Thompson, as far as navigation clearance, is an unrealistic option. The additional costs of a larger structure and impacts of extended touchdowns on each side of the river, as well as Hayden Island and surrounding communities would be significant.”

Two other companies are next to Thompson, each doing similar large-scale fabrications. Greenberry Industrial, of Corvallis, leased space in 2010 and Oregon Iron Works bought 7.5 acres. The fabricators ship on the river only a handful of times a year. But their cargoes are often too large to clear the 95-foot span originally proposed over a decade ago. They required “mitigation” with the 116-foot former CRC proposal.

The existing bridge is in the same league with the Astoria-Megler Bridge (193 feet), the Longview span (187 feet) and Interstate 205 Glenn Jackson Bridge (144 feet). A 116-foot replacement bridge would require mitigation under government rules. What bridge height is possible, that wouldn’t require mitigation?

A bridges’ vertical clearance varies, of course, with the ebb and flow of water levels. The original proposed 95-foot height of the new I-5 bridge would offer clearance of between 78 and 95 feet, according to the CRC a decade ago. That seven foot variance in water level would seem to indicate the new proposal could actually offer clearance less than 110 feet during times with high water levels.

“The concept of taking a bridge and making it lower is so contrary to common sense,” said Tom Hickman, vice president of sales and marketing for Oregon Iron Works roughly a decade ago. “We’re kind of baffled how they got this far down the road without listening to the concerns. They seem to have just ignored us.”

A 2019 audit of the CRC by the Oregon Secretary of State (SOS) reported the following.

“The Independent Review Panel also recommended that the project team revisit the height of the proposed bridge based on feedback from local marine contractors. At the time of their review, the proposed bridge had a clearance height of 95 feet, approximately 80 feet lower than the current bridge with the lift span raised. However, several river users had loads of 110 feet with planned loads as tall as 140 feet. This concern led to further design revisions.”

In June of 2013, two of the firms reached an agreement to be paid “mitigation” in order to allow the project to move forward. A couple months later, the final agreement would have paid a reported $86.4 million to the three firms, with nearly $50 million going to Thompson.

Rudi said at the time, Thompson planned to build a second “satellite” facility downstream of the new bridge, from which it would ship its largest products. Thompson hoped to keep all of its operations in Clark County.

Pearson Airport

The Pearson Airport is situated less than a mile east of the current bridge. The end of the runway is just under 2,600 feet from the current bridge. Many pointed to the small airport as a restriction on constructing a structure with higher clearance.

But people in the community point out that Pearson has been coexisting just fine with the current I-5 bridge, whose lift towers are about 230 feet high. The lift span is capable of moving 136 feet vertically, and provides about 178 feet of clearance below when fully raised. The towers are 190 feet tall.

Willy Williamson, Pearson manager during the CRC, watched the unfolding controversy. A higher span is not a problem, as far as he’s concerned, though ultimately the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) will consider the CRC’s plan.

“Raising the bridge 30 feet is not going to hurt us,” Williamson said. “Fifty feet may be a different matter. But that’s the FAA’s call.”

This news report from November 2020 highlights when the US Coast Guard told the IBR team members they would need to get a new permit. Many river users have to call for a bridge lift due to the fast moving water current and the need to do the “S curve” to safely navigate the BNSF rail bridge one mile west.

Transportation architect Kevin Peterson is also a private pilot. He shared that the previous designers used an incorrect glide path calculation for Pearson airport in the CRC design. The current team should have more flexibility in offering a proposed bridge design.

A decade ago, Thompson officials went to the Coast Guard and found a sympathetic ear. “I find that the vertical clearance for the proposed I-5 bridge does not fully address the reasonable needs of navigation for vessels which ply this stretch of the Columbia,” said Randall Overton, Coast Guard bridge administrator, in an October 2011 letter. Overton reprimanded the CRC for not including mention of the fabricators’ needs for a higher bridge in its environmental impact statement when it knew of the conflict.

The Coast Guard is not just another federal bureaucracy. In keeping with its charge to protect navigable waters, it essentially has veto power over the bridge.

In response, the CRC proponents essentially said that they knew best. “We have confidence that the technical work that has been in process for the past several years is a sound body of work,” said Paula Hammond and Matt Garrett, the heads of the Washington and Oregon departments of transportation in a November 2011 letter to the Coast Guard. “A project of this magnitude must address the total array of users in the decision making process and the 95-foot clearance meets those needs.”

That was a nonstarter as far as the fabricators were concerned. “You might as well bankrupt us,” said Jason Pond, CEO of Greenberry at the time. “I just don’t get it. This is a project that’s all about jobs. I just assumed that they wouldn’t kneecap these companies that are offering great jobs.”

The failed CRC was deemed “a light rail project in search of a bridge” by an Oregon Supreme Court Justice. It was often discussed that the “bridge too low” was caused because TriMet’s light rail was unable to safely climb a steeper bridge design. The current effort can recommend bus rapid transit for its high capacity transit solution and not have to deal with the light rail problem.

The Columbia River is its own transportation corridor for marine traffic. Some recreational sailboats have very tall masts that have required current bridge lifts. The three mentioned manufacturers create significant numbers of jobs and economic prosperity within Clark County.

In the urban environment of the Portland metro area, there are airspace needs for two airports. There are freight, private, and transit vehicle transportation needs for crossing the river. But marine traffic is generally recognized as needing the most protection, and federal laws give special consideration to marine traffic.

Mariners and maritime stakeholders are requested to express their views, in writing, on the proposed bridge and its possible impact on navigation. The Coast Guard specifically requests “requirements for horizontal navigation clearances and vertical navigation clearances to include air draft and air gap requirements. The Coast Guard is particularly interested in receiving comments from maritime stakeholders with vertical navigation clearance requirements of greater than 116 feet.”

Comments should be sent to: Commander (dpw), Thirteenth Coast Guard District, 915 2nd Ave, Rm 3510, Seattle, WA or via email at mailto:D13-SMBD13-BRIDGES@USCG.MIL. Comments should be sent to arrive on or before April 25, 2022.

The IBR team will reveal specific details of its proposed replacement bridge on April 21. There will be a great deal of interest on all aspects of the proposal, including Hayden Island impacts, the final number of lanes on the bridge, and the form of transit being proposed.

Thompson Metal Fab, Oregon Iron Works, and Greenberry Industrial officials will be watching closely to see if the IBR team is creating a new stop light on the Columbia River for marine traffic. They know the top of the current two structures is about 230 feet high. They know the current bridge lift clearance of about 178 feet serves them well.

It looks like once again the design is simply to exchange a vehicle stop light for a commercial dam – without navigation locks – blocking full function of the otherwise very usable Columbia river.

Clearly buses are a better option for bridge height, saving $ on the building of a replacement bridge, flexibility in vehicle size, and sharing a lane with other vehicles.

Light rail serves only 1-2% of commuters, yet accounts for as much as 1/3 of the projected bridge replacement costs. This is irresponsible.

If buses are used for the transit service across the river, as is the case now, there is no need for costly tolls. ( How much of the toll goes to the toll collector?).

All of these articles should be summarized and presented to the IBR group so that a bridge replacement can be built to serve ALL users. Roads for all vs. gold plated light rail for a very few, and zero freight. The Light Rail Cartel continuously underestimates true costs of light rail, and greatly exaggerates the number of residents who will use light rail. None of the CRC inflated predictions of bus ridership have come true yet.

Bridge lifts for recreational vessels for the wealthy during peak traffic times should be halted. Bridge lifts have been allowed for a single recreational vessel as early as 6 pm, which is still a peak traffic time. If recreational vessels are going to be allowed to request bridge lifts, it should be limited in number and at set times, so everybody can plan on it. Large boat owners can line up, and all utilize the lifts at the same time, instead of individual lifts for every large boat owner who requests them, one by one while all the traffic, buses, and freight wait.

Last time, the CRC was not thorough in their outreach to those using the bridge lift. Hopefully the IBR will contact these businesses ASAP about their navigational needs. Have those who haul freight across the bridge day and night and their associations been contacted? What about individual truckers? Do they know the cost of tolls by the axle for their vehicles? These toll rates for the 520 bridge in Seattle are scheduled to increase.

https://wsdot.wa.gov/travel/roads-bridges/toll-roads-bridges-tunnels/sr-520-bridge-tolling