Where are the missing 50,000 light rail passengers?

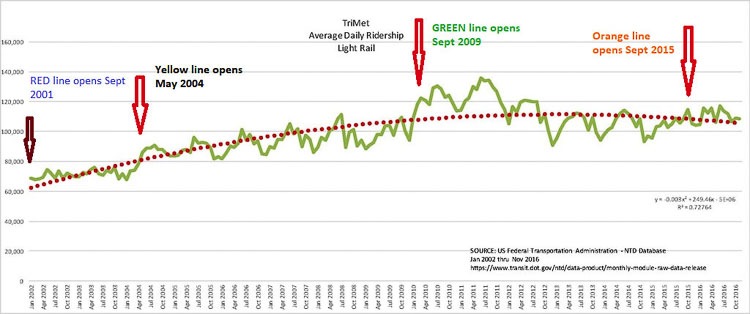

In the past two decades, TriMet has opened four new MAX light rail lines. The Red Line connecting the airport to downtown opened in 2001. The Yellow Line opened in 2004; the Green Line in 2009, and the Orange Line in 2015.

Total MAX ridership peaked a decade ago in 2012 at 35 million originating rides, declining 12 percent to just below 31 million in 2019 before the pandemic. The addition of two new light rail lines failed to stimulate ridership. TriMet officials appear to be on track to be short of their optimistic projections by over 50,000 passengers for just two of those lines.

Travel times are nearly 50 percent longer than TriMet promised citizens. The $350 million Yellow Line, with its multiple stops in north Portland, travels an average of 14 miles per hour (mph).

As the Portland metro area prepares to learn important details regarding the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) program, critical facts should be key to the choices offered to the decision makers on the Executive Steering Group (ESG) and the Bi-state Bridge Committee of 16 legislators. Those include the number of total lanes across the bridge; the Hayden Island interchanges, and the height of the bridge to accommodate marine traffic.

Due to the highly contested Columbia River Crossing (CRC) debate, the critical issues of tolling and the type of mass transit will be front and center for Clark County residents. Decision makers should be presented with all the details and options, and then be allowed to decide each of these components.

Clark County residents strongly opposed bringing TriMet’s MAX Yellow Line light rail into Vancouver not only a decade ago, but from the beginning. A 1988 plan was scrapped after Clark County voters defeated a proposal to raise $236.5 million in 1995 and Oregon voters turned down a $475 million regional ballot measure in 1998.

In fact a report to the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) highlights planning actually began 40 years ago for light rail to Vancouver. What has changed since then regarding mass transit and light rail?

Six of the IBR team’s “options” for high capacity transit on the proposed bridge include light rail; five of which run along I-5 real estate instead of connecting with the downtown Vancouver Turple Place transit hub. Why wouldn’t they connect two forms of transit service?

Broken light rail promises

The Yellow Line MAX light rail line opened to great fanfare in May 2004. The Yellow Line’s final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) made a myriad of predictions for the year 2020, including high ridership, frequent service, and quick travel times. None of these promises were ever delivered by TriMet.

The Cascade Policy Institute’s Rachel Dawson laid out the details in a September 2019 point paper. This highlights pre-pandemic levels of failed service. Additional details were provided in a “before and after” report to the Federal Transit Administration (FTA).

TriMet officials promised the FTA in their Full-Funding Grant Agreement (FFGA) that peak-hour trains would arrive every 10 minutes and off-peak trains every 15 minutes. The promised service according to the EIS was supposed to reach eight trains during peak hours in 2020, or one train every 7.5 minutes.

Instead of having 10-15-minute headways between trains, the Yellow Line currently runs every 15 minutes during peak-periods and every 30 minutes during other parts of the day.

TriMet predicted travel times to be 24 minutes from downtown Portland to the Expo Center and 19 minutes from downtown Portland to N Lombard. Light rail speeds were projected to reach 15.3 mph, and bus speeds were projected to be 13.2 mph in 2005, making light rail faster.

Actual light rail travel times are longer and speeds are slower than predicted.

It takes 35 minutes to take light rail from downtown Portland to the Expo Center and 28 minutes from downtown Portland to N. Lombard St., even though light rail has its own exclusive right of way. Actual travel times are 46 percent longer to the Expo Center and 47 percent longer to N. Lombard St. than promised. Actual light rail speeds in the corridor only hit 14 mph in 2005, whereas bus speeds averaged 16 mph — significantly faster than predicted.

Who wants to travel 14 mph going to and from work?

The EIS forecasted ridership in the corridor would dramatically increase with the building of the Yellow Line. By 2020, the line’s ridership was expected to have 18,100 average weekday riders. It was 5,290, with a shortfall of 12,810 riders.

At no point since the Yellow Line opened has ridership met projected levels. In April 2019 ridership only reached 13,270, over 26 percent less than projected. This number did not meet 2020 projected levels. From March 2016 to March 2019 ridership levels decreased by 3.6 percent. The pandemic lockdown caused transit ridership to decline roughly 70 percent.

Lower than promised ridership isn’t unique to the Yellow Line. Every TriMet light rail forecast has been wrong, and always wrong on the high side, Dawson reported.

The Yellow Line was expected to provide superior service compared to the no-build bus alternative. This forecast hasn’t panned out. The $350 million Yellow Line replaced bus service (Line #5), which if it were still operating, would have seven-minute headways between Vancouver and downtown Portland. C-TRAN express service was forecasted to have three-minute headways according to Carson.

Light rail does not reach any more people or businesses than Line #5 did. In fact, Line #5 had more stops along Interstate Avenue, meaning some riders now have a longer walk to get to the MAX stations.

TriMet bus service from Vancouver to downtown Portland continues to be an option even after the Yellow Line’s construction. Line #6 was changed to pick up the link between Jantzen Beach and the Yellow Line’s Delta Park stop that Line #5 had previously served. It then continues down MLK Boulevard to the Portland city center.

In Spring 2019, Line #6 saw 665 average weekday on/offs at Jantzen Beach and only 190 total on/offs at Delta Park. The vast majority of Vancouver commuters on Line #6 opt to stay on the bus to Portland instead of transferring to the Yellow Line light rail, according to Dawson.

The 2019 data showed the Yellow Line had 120 rides per every hour the vehicle was in operation. The average trip length was 3.2 miles, clearly not taking many vehicles off the freeways for trips that short.

TriMet reports in 2021 the cost per boarding rider on their MAX light rail was $9.08. The cost per vehicle hour is $449, whereas the operating cost per hour of a TriMet bus is $116.

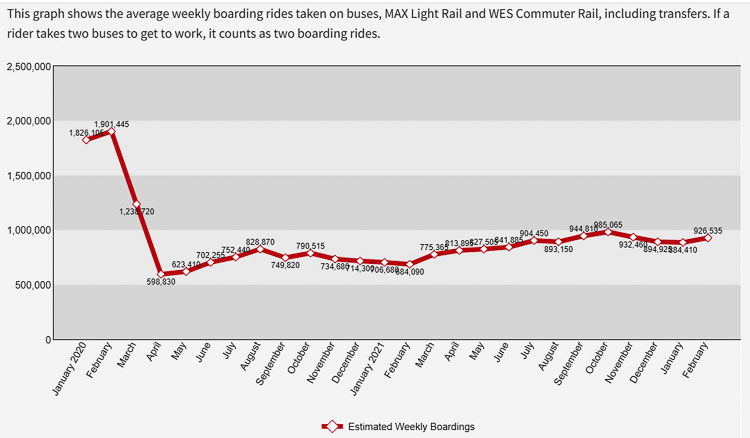

C-TRAN recently slashed their express bus service across the Columbia River as their ridership on seven separate express lines declined to less than 1,000 people daily due to the pandemic. TriMet has reported it will take six years for ridership to return to pre pandemic levels.

The Green line problems

The TriMet Green MAX Line under-performs as well. “Some trips that actually use the Green Line were shifted in the ridership predictions to the artificially fast bus services,” was the excuse TriMet officials used in their report to the FTA.

Green Line service was promised at 10 minutes between trains during weekday peak periods and 15 minutes during other times. The project opened with 15-minute intervals throughout the day and 35-minute intervals in the evenings. Service remains at 15-minute headways during much of the day.

When the FTA completed its 2015 “Before and After Study” on the line, there was an average 24,000 daily weekday boarding rides. This was 19 percent below the 30,400 riders that TriMet predicted in their preliminary engineering for the line’s opening year.

That number has continued to decrease to just over 16,000 average daily riders in August 2019, making up only 34 percent of the FEIS’s predicted ridership levels for 2025. With just over three years to go until 2025, it seems unlikely that the Green Line will attract the additional 30,500 riders needed to hit TriMet’s promised level of 46,500 boarding rides.

In 2020, it carried just 7,980. That’s a shortage of over 38,000 riders on the Green Line. When added to the 12,000 shortfall on the Yellow Line, TriMet is missing over 50,000 boarding riders.

Unsurprisingly, the line’s cost was higher than TriMet originally anticipated. The final price tag of $576 million was 14 percent greater than the anticipated cost in preliminary engineering, a difference of about $70 million.

A Feb. 2020 news report indicated TriMet downgraded its estimate of the number of daily passengers the newest Orange line would serve to 37,500, down from 43,000. The lowered number illustrates what a moving target ridership can be. TriMet has struggled to meet projections for the Orange Line, which since 2015 has run between downtown and Milwaukie. They did not meet TriMet’s first-year projections by nearly 6,000 riders a day.

The 2020 report shows Orange line ridership at 3,350 weekday riders. That is down over 70 percent from 2019 numbers of 12,160 riders. This would add nearly 40,000 missing riders from when the project was initially sold to the community.

Crime increased

Instead of the promised passengers, light rail brought increased crime to the Clackamas Town Center area. Clackamas County experienced heightened crime in the corridor from 2009-2012 after the Green Line opened and an increase in graffiti around MAX stops, according to a survey by the Oregon High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas Program sent to the Clackamas County Sheriff.

Last month a man was shot on the green line. Last November a Green Line MAX driver prevented an attempted stabbing at the Clackamas Town Center stop. The MAX system still saw more violent acts and other major security incidents in 2017 than any year since TriMet began reporting to the FTA in 2008.

TriMet’s own crime statistics for 2017, showed 63 reports of aggravated assault against customers, an increase of 43 percent. Reports of simple assault, resulting in minor or no injuries, climbed 81 percent, to 168. Half of those crimes occurred on the MAX system, while about a quarter occurred on buses.

Things have gotten so bad that in January TriMet confirmed that police won’t be checking passengers for fares, but instead will be seeking to protect drivers and passengers.

Citizens on both sides of the Columbia River have concerns about MAX light rail. In 2020, metro area residents in Oregon rejected a $5.2 billion bond measure that would have allocated roughly $2.9 billion on a new light rail line to Tigard/Tualatin. The measure was defeated in all three counties, 58 percent voting no.

Eight months prior to the vote, TriMet lowered passenger estimates. The planned $2.9 billion light rail line between downtown Portland and Bridgeport Village in Tigard would serve 12 percent fewer passengers than previously forecasted.

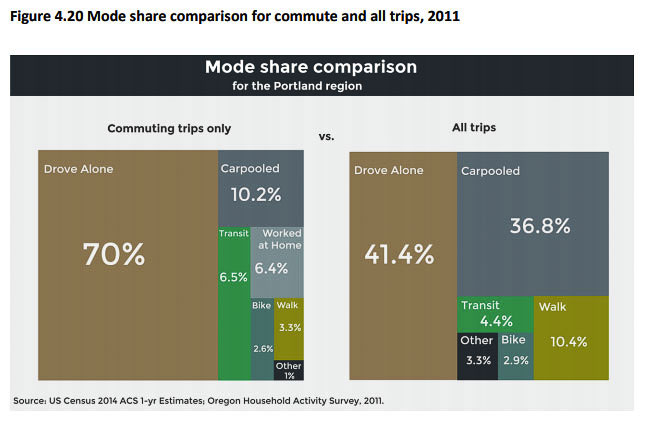

The 2018 PEMCO survey reported 94 percent of people in the Portland area prefer to use their cars. Their private vehicles were faster and more convenient than riding transit. Over half respondents said they wouldn’t make any changes and another 15 percent they would drive more often if they could. That was before the pandemic where mass transit experienced 70-80 percent declines in ridership nationally.

Oregon Transportation Commissioner (OTC) Robert Van Brocklin recently said only 4 percent of people in Portland use transit. Other data indicates while some Portland neighborhoods use transit at a much higher rate, the broader metro area transit ridership remains low. Since the IBR is a regional issue, how likely is it that the region will embrace greater transit ridership across the Columbia River?

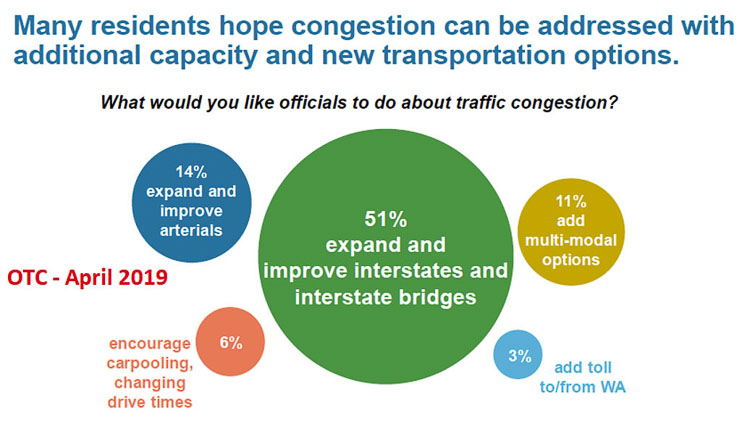

An April 2019 OTC survey asked “what would you like transportation officials to do about traffic congestion?” The responses indicated 51 percent want to “expand and improve interstates and interstate bridges.” Another 14 percent want to “expand and improve arterials.” That makes 65 percent of Oregon respondents want to expand vehicle capacity and improve roads to reduce traffic congestion.

The IBR team members appear to be favoring extending the Yellow Line into Vancouver, in spite of data showing few people will ride it. They have said there is “substantial demand” for high capacity transit, but haven’t provided that data.

In 2013, John Charles of the Cascade Policy Institute called for local jurisdictions to leave TriMet. “After 44 years, it’s time to admit that TriMet has failed,” he said at the time. “Its cost structure is too high and cannot be reformed. The policy objective from now on should be to serve transit riders, not the TriMet bureaucracy.” Charles feels even stronger about that advice today.