Absolute and irrevocable contract given to TriMet for eminent domain control over transit

During the community discussion about the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) with its proposed light rail coming into Vancouver, one popular concern was the potential for Clark County becoming financially tied to TriMet, the transit services provider for the Portland Metropolitan area. In addition to concerns about tolls and the “no light rail, no bridge” demands of politicians, some citizens voiced concerns about getting entangled financially with TriMet.

A separate battle emerged in 2013 as C-TRAN gave TriMet control over eminent domain authority, in an “absolute and irrevocable” contract that contained a $5 million penalty clause. That contract remains in force today, adding to citizen concerns.

With the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program underway and numerous legislators including Oregon’s Congressman Peter DeFazio demanding light rail be added to the project, citizens should ask about financial ties to TriMet. TriMet has roughly $2 billion in total debt and financial obligations, compared to C-TRAN essentially being debt free.

In 2012, a TriMet General Managers Budget Task Force stated the following: “TriMet must first demonstrate it is making progress controlling its labor costs before it can be seen as a wise investment worthy of additional revenue.”

The annual report concluded with the following: “TriMet 2025, a bleak picture.” They said: “On our current path by 2025, we would need to either cut bus service by 70% or raise the price of an adult two hour ticket to $8.50.”

Has TriMet significantly improved their financial position? Have they become “worthy of additional revenue?”

Should Clark County taxpayers welcome a partnership with TriMet? Or should they be concerned about creating a permanent financial tie to a transit system that is in financial trouble?

Today, TriMet appears to have nearly $2 billion in debt and unfunded pension and retiree benefit obligations according to their most recent financial statement.

In November 2020, voters in the three-county area rejected a $5 billion Metro transportation bond by a 58 percent to 42 percent margin. The single biggest project was the $2.9 billion Southwest light rail extension. The measure failed in all three counties, Multnomah County, Washington County, and Clackamas County.

That vote could be interpreted as voters signaling they don’t believe TriMet is worthy of additional taxpayer money. Earlier in the year, Portland voters approved a 10 cent gas tax extension by a 77 to 23 percent margin of victory.

C-TRAN serves as Clark County’s mass transit provider. It has no long-term debt; no unfunded pension obligations for retired employees. C-TRAN’s financial picture is very different from TriMet’s.

In 2013, citizens asked how much of TriMet’s debt and financial obligations would Southwest Washington taxpayers be on the hook for if light rail was included in the CRC. That question remains valid today as both Governors and many legislators are demanding light rail as part of the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) discussions.

Unfunded TriMet liabilities

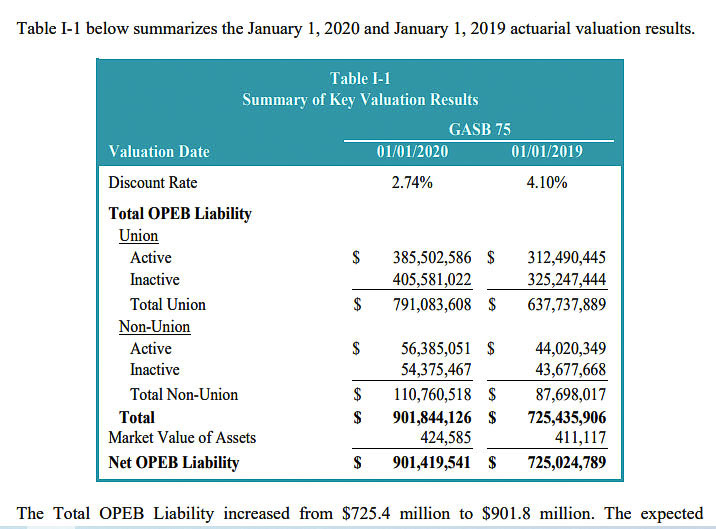

Presently, TriMet has an $901 million unfunded Other Post Employment Benefit (OPEB) obligation. That’s up from $725 million a year earlier. The current obligation equals 26.95 percent of payroll.

Added to that is $182 million unfunded pension liability for 2020, up from $139 million a year earlier. The pension funding ratio declined from 80.5 percent to 75.9 percent funded. The unfunded pension liability was $123 million in 2013.

TriMet pension liability has increased 39 percent from $542 million in FY2012 to $756 million in FY2020.

The total unfunded liabilities for TriMet retirees appear to be $1.083 billion when adding pension liabilities and the OPEB obligations.

Long-term debt on TriMet’s books in 2013 was $711 million. Seven years later their long-term debt was $853 million as of June 30, 2020; a 20-percent increase.

A decade ago (October 2011), John Charles of the Cascade Policy Institute stated the following. “TriMet’s off book debt for unfunded retirement obligations has swelled to $1.1 billion. The pension plan for union members is only 56 percent funded, the plan for management 68 percent percent funded, and the liability for other post employment benefits, which is mostly healthcare, is completely unfunded.”

In 2013, the year the CRC was defeated, TriMet debt increased 55 percent. Noncurrent liabilities consist primarily of long-term debt, long-term lease liabilities and OPEB liabilities. Total long-term debt jumped from $319 million to $751 million in one year.

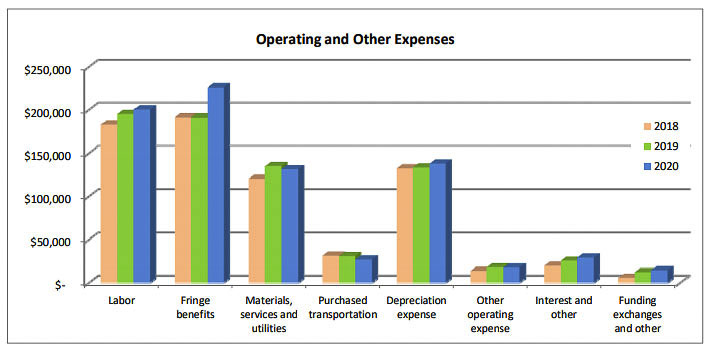

It would appear a decade later, very little has changed. In 2020, fringe benefit costs now exceed labor costs.

Debt service equals 20 percent of operating costs

TriMet’s financial report states “total day-to-day operating requirements of $732.8 million, which includes $610.2 million for all activities required to operate the system (including other postemployment benefits) and $122.6 million for debt service.” Debt service equals 20 percent of operating costs, as it has $853 million in long term debt.

In Dec. 2019, TriMet adopted an Amended Strategic Financial Plan that laid out the seriousness of TriMet’s financial position. In the words of TriMet’s own staffers: “Financial challenges threaten TriMet and the viability of transit.”

The plan stated: “TriMet plans to have all pension plans fully funded in 15 years or sooner. TriMet’s $950 million OPEB liability was reduced through eligibility and benefit reductions by 25%. TriMet has targeted a reduction in its OPEB liability by the time the pension plans are fully funded and then allocating the same stream of pension funding to funding an OPEB trust until the OPEB liability is fully funded as at least 93 percent.”

Will TriMet really have their huge OPEB funded by 2035, as their 2019 plan predicts?

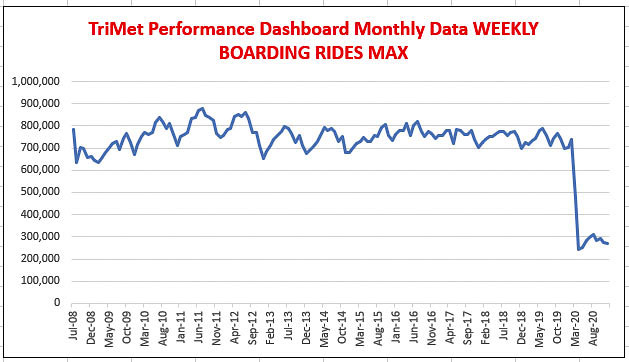

The FY 2021 annual report for the year ending June 30 won’t be published for several months. Yet we know due to the pandemic, transit ridership (and passenger fares) fell off a cliff. While ridership numbers have begun increasing, many experts predict it will be years before passengers return to riding mass transit at pre-pandemic levels. Earlier in the pandemic, TriMet reported MAX ridership had declined by 60 to 70 percent.

Therefore TriMet’s 15-year plan to get their unfunded OPEB to a mostly funded status is likely off to a rocky start. With long-term debt increasing, there doesn’t appear to be any projections that TriMet will ever match C-TRAN as a “debt free” transit agency.

TriMet’s light rail service decline

In June 2013, Charles wrote the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) discussing the failure of TriMet to live up to their FFGA (Full-Funding Grant Agreement) promises when obtaining funding for its green and yellow lines.

“TriMet is also in violation of its FFGA for the Yellow MAX line. That line opened in 2004 with 605.4 weekly revenue service hours. By the fall of 2012, service had dropped to 568.4 weekly revenue hours, a loss of 6 percent.

“Peak-hour service on the Yellow Line was supposed to operate at headways of 10 minutes in the opening year, improving to 7.5 minutes by 2020. Instead, peak-hour headways are currently 15 minutes.”

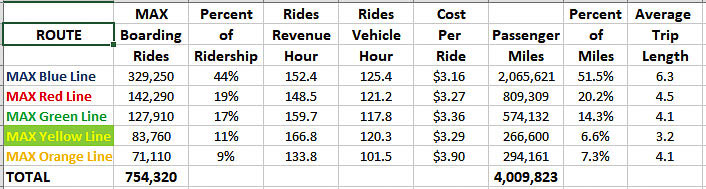

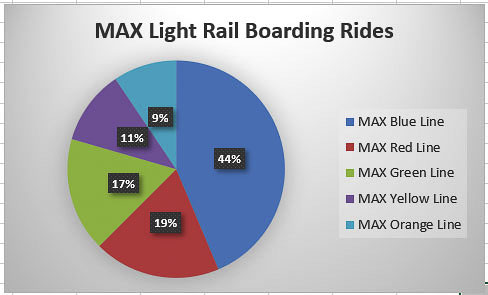

Present Yellow Line service eight years later continues at 15-minute headways during most of the day. The service carries just 11 percent of MAX ridership and is number four of five for total passengers carried. The Blue Line carries almost four times as many passengers.The Orange Line (TriMet’s newest) remains in last place.

But broken promises with the Yellow MAX line are not the first from TriMet. “Service hours for the Green Line were reduced by 33 percent before it ever opened in September 2009,” Charles said. “Service has continued to decline since then. Weekly revenue hours have dropped from 692.4 in the opening year to 686.3 in the fall of 2012, a loss of 1 percent”.

The MAX Yellow line departs most of the time every 15 minutes from the Expo Center beginning at 6:37 a.m. presently. Prior to that it offers service every 30 minutes starting shortly after 5 a.m.

TriMet data for 2019 shows the average trip length on the Yellow line is 3.2 miles. Trip time is 35 minutes from Expo to PSU south, and travel 5.8 miles with 17 stations. Trip speed is 10 mph. The average passenger travels just under half the distance of the Yellow line service.

Average trip lengths of about 4.4 miles for the entire MAX system suggest it does not carry long distance commuters. The Yellow Line carries its average passenger the shortest distance of all five MAX lines.

The Yellow Line is the fourth-busiest MAX service, of the five MAX lines. It averaged 12,960 riders on weekdays in September 2019, down from 13,170 for the same month in 2018. Ridership projections in 2003, several months before the line’s opening, expected 13,900 passengers per day during the line’s first few years, growing to 20,000 daily passengers by 2020.

For the 2015 fiscal year, the Yellow Line recorded 4.9 million total boardings, down from 5.4 million recorded in 2012. The drop in ridership, experienced system wide, was attributed to crime and to lower-income riders being forced out of the inner city by rising housing prices, according to one report.

The Portland Mercury reported three years ago about the declining TriMet ridership.

“TriMet data analysts have blamed the dip in TriMet ridership to the pattern of lower-income, bus-riding Portlanders being pushed out of inner city neighborhoods due to creeping housing prices. Many have fled to the city’s outskirts or surrounding towns, areas with less frequent TriMet services.

“This trend leaves us with big, probably uncomfortable question: What population is Portland’s public transit catering to?

“Tourists, businesses, and higher-income residents of downtown Portland dodging rush-hour traffic? Or the lower-income carless Portlanders who depend on reliable transit to run errands, get to work, or see family?”

The Portland Tribune reported TriMet has only tracked ridership by line in 2016 and 2017, so information before that is unavailable.

A TriMet document reports the history of the Yellow line.

“The project was originally part of a longer extension, the South-North light rail project, which would have stretched from the southern suburb of Milwaukie through Portland and across the Columbia River into Vancouver, Washington.

“Clark County, Washington, voters rejected financing their segment of that line in 1995. Three years later, the Portland region rejected a property tax increase for a revised Oregon-only project, although it was supported in Multnomah County and in the City of Portland.”

Questionable tactics regarding eminent domain

A separate battle unfolded in the fall of 2013. C-TRAN staff signed a contract with TriMet that no Southwest Washington citizen, nor the C-TRAN board, saw prior to its signing.

That contract ceded C-TRAN’s eminent domain authority to unelected staff at Portland’s TriMet. No Southwest Washington citizen wants an unelected, unaccountable person or group in Portland, to have the ability to take its personal, private property.

Furthermore, the contract included a $5 million penalty clause. This meant that if C-TRAN failed to live up to the terms of the deal, Southwest Washington taxpayers would be on the hook for $5 million. At the time, the $5 million represented almost 60 percent of annual farebox revenues for C-TRAN.

Finally, the staff included language that said the contract was “absolute and irrevocable.” Who signs an “absolute and irrevocable” contract?

When a person buys a car, there are “lemon laws” and “buyers remorse” laws giving people several days, and sometimes weeks to back out of the deal. When people buy a house and go to closing, they are given several days after the closing to change their minds, to re-read all the contractual paperwork and reconsider. In this case, it appears the C-TRAN CEO and attorney thought an “absolute and irrevocable” contract was appropriate.

Citizen outrage followed. In the summer of 2014, the C-TRAN Board directed staff to ask TriMet to rescind the contract. Not surprisingly, the answer was “no.”

That “absolute and irrevocable” contract with the $5 million penalty exists today. It gives TriMet the ability to take the private property of Clark County citizens. In the case of the replacement Interstate Bridge, if light rail is included in the project, TriMet will use C-TRAN’s eminent domain authority to take the property of downtown Vancouver businesses and citizens.

Given all these realities, can TriMet ever be a trusted partner to Clark County citizens, if light rail were made part of the IBRP? Is there any way Southwest Washington citizens can be immunized from any obligation to pay a portion of the $2 billion in TriMet debt? Should Clark County taxpayers “invest” any money in TriMet, given that a TriMet task force said they were unworthy of additional investment in 2012? When will transit ridership return to pre-pandemic levels?

There are more questions than answers at this point.

When I got back in office I met with the leadership of trimet. I asked twice if they would consider ripping it up so there would not be a roadblock in a new bridge attempt. The answer was no both times.

If only you had been a loud, vocal opponent to the entirety of this massive rip off, and not just this tiny portion of it.

You supported the CRC when it needed militant opposition. And now, look what’s facing us.

All of the same reasons to kill this deal remain in effect today as they did in 2013. Nothing has changed except now, Rivers is leading the parade of GOP turncoats who have flipped their positions.

“Reframed their thinking.” “Removed the congestion component,” What was a massive waste of billions has become even worse.

Bla bla bla. The article was about the contract. Can you read

Very informative. John Ley is the man. Watchdog for Clark County.

Maybe the best course of action would be to renounce the contract and let Trimet sue. Or pay the $5 million and send the bill to the GM who tricked the board, and the attorney who did not blow the whistle.

What did TriMet get out of the “absolute and irrevocable” contract – why did they sign it?

John —

TriMet is holding it in their files for when they build a MAX light rail extension into Vancouver. They will then use it to condemn any property they see fit as a “need” for their light rail extension.

It removes any “future impediment” so they no longer need the approval of the C-Tran Board of Directors, as they already have it.

I say, forced “light rail” — no bridge. As the facts and figures show, Tri-met has come nowhere close to the cost or usage estimates initially made to justify the substantial expense of building the system. To give such an agency the ability to tax Clark County citizens for a deficit engorged transit agency is the height of folly. It is a sad fact (one that rail promoters wish to ignore) is that “light rail” systems built in the past 40 years have generally cost double the initial estimates, and have carried half the passengers. Note that the statistics quoted are weekly (not daily) “boardings” (what does that mean, exactly?). Just as much weight is given to one who rides a trolly car for block as one who travels downtown from the end of the line. Furthermore, a well known “hike” is the “5 Ts” riding trains, trolleys, and walking a trail that results in 4 “boardings” — using one paid ticket in one day. (Indeed, I’m told that ticket scanning is a “sometime thing” and that people board (and leave) trains frequently without scanning tickets — or even if they have tickets at all. (Yes, there is supposed to be enforcers, but Portland is not even able to lock up rioters, so why should be expect that they’re “policing” the fare box of Tri-Met? The only possible reason Tri-Met (and the Oregon politicians) want to get a toe-hold in Clark County is to assert the “need” to tax Clark County citizens to support the failed Tri-Met system.

I note that progressive politicians “love” expensive “light rail” transit systems because they create considerable cash flow to pay off favored contractors and also create a “mandatory” unionized membership that pays dues that are used to keep progressive politicians in office. (Note — this process of creating large unionized groups of public workers is what has destroyed the once livable state of California.) Doubt? Just consider the “forensic accounting” made of the hundreds of $millions spent on the CRC “preliminary study” that resulted in a failed proposal.

Reading these letters are encouraging in that you all have a clear idea of what we will face again in dealing with Oregon. The Tri Met board will attempt to obligate SW Washington for every penny they can get out of us. They will force MAX on us with no real benefit to us and we will have no say.

It seems as if Oregon thinks of us as their colony and Olympia doesn’t object.

Those ticket enforcers you speak of will be in FORCE on this side of the river to be sure. Just watch they’ll be checking tickets multiple times for one rider.

No crime train for Vancouver!