The bond would build two new schools, replace the high school vocational building, and upgrade several playgrounds

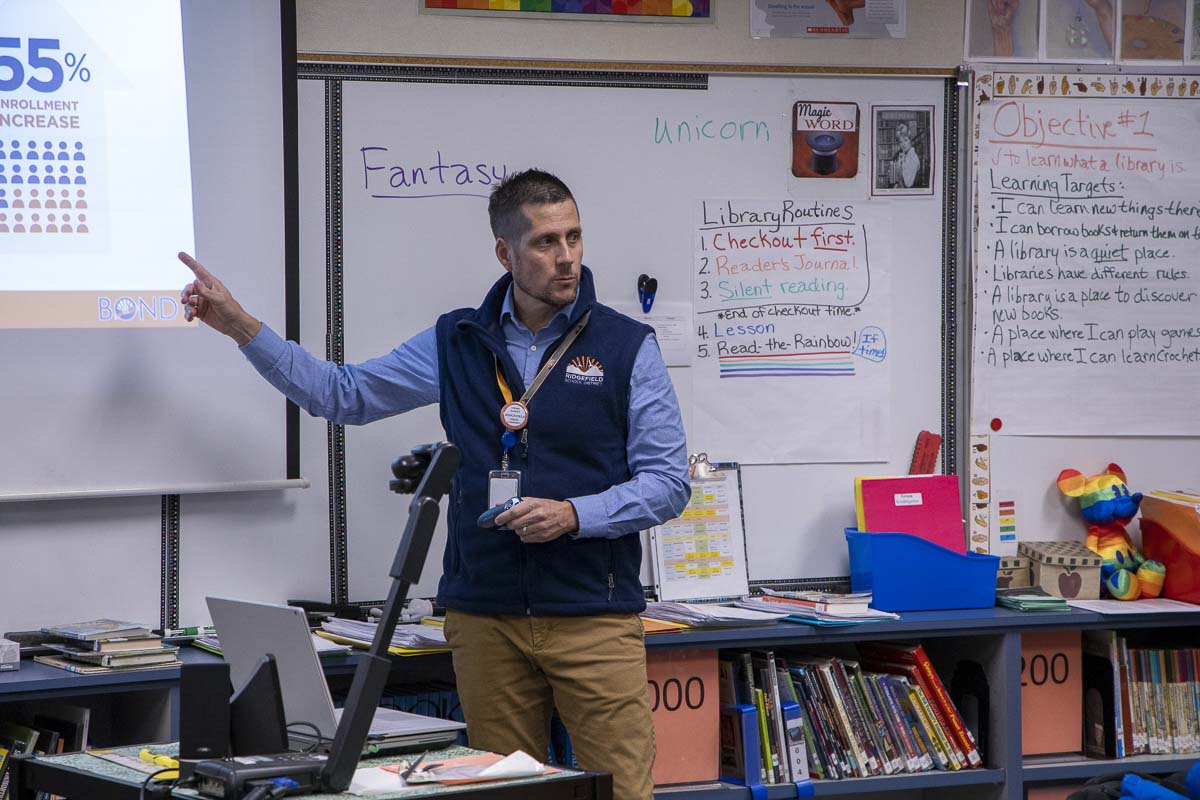

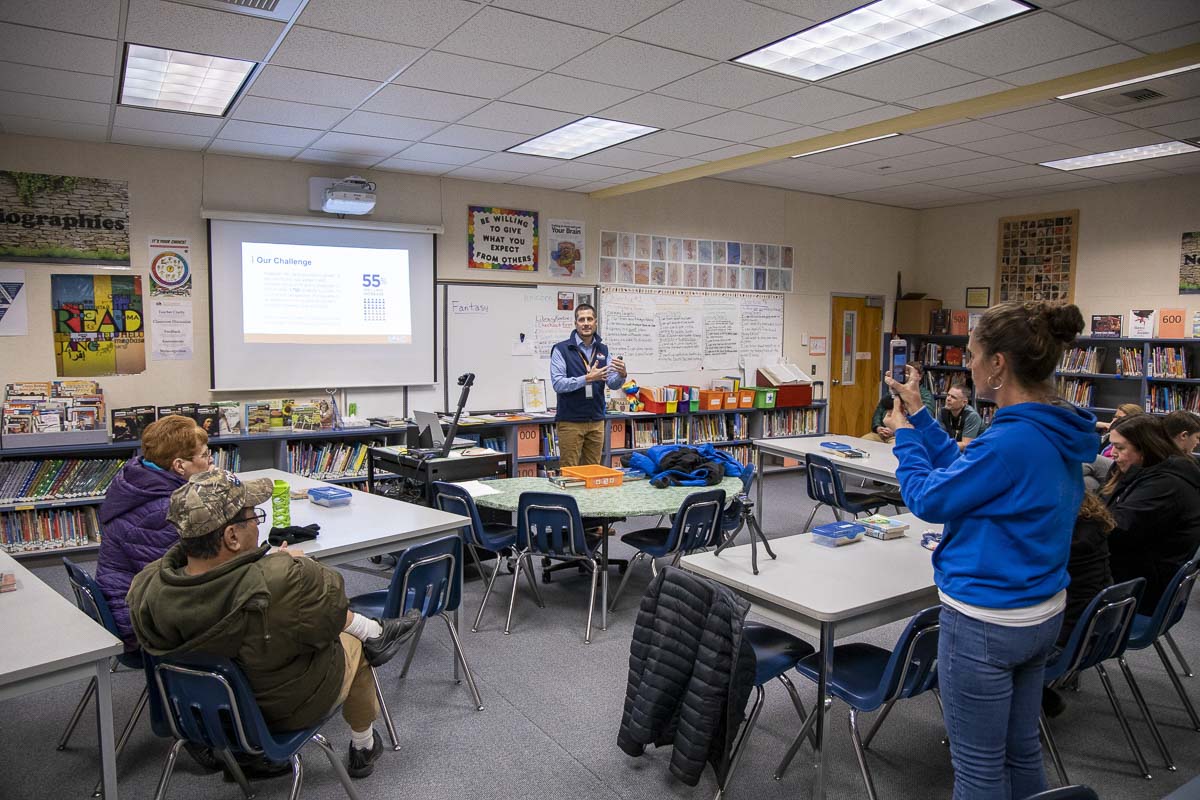

RIDGEFIELD — Wearing a dark blue Ridgefield School District vest over a light blue button-up shirt, Nathan McCann delivers his pitch to a small group gathered inside the library of South Ridge Elementary School on a Thursday evening.

It’s a speech McCann has given many times before as the superintendent of Southwest Washington’s fastest-growing school district tries to guide another building bond through following a rare setback last February.

“I’ve lost track of how many of these I’ve done. I’ve done these in churches. I’ve done these in schools. I’ve done these in restaurants,” McCann says. “We keep doing this because it’s important. Because we want to engage with as many folks as we can.”

While only a handful attended Thursday’s meeting — the third out of four open forums which conclude tonight at Ridgefield High School — McCann says more have watched and engaged through social media and their website.

Up until last year, Ridgefield had an almost unblemished record of supporting its school district. Two previous bonds passed with relative ease. But the third phase, a $77 million bond, fell about 1.1 percent short of the 60 percent-plus-one vote majority needed to pass.

Many voters, it appeared, had been left shell-shocked by property tax increases that hit in 2018 as part of the McCleary education funding package approved by the state legislature.

Taxes dipped again this year, but property owners remain wary, with a 30-cent per thousand one-time property tax relief expiring on Jan. 1.

And this time around Ridgefield is asking for more, $30 million more.

The $107 million bond would be supplemented by about $17.3 million in state matching funds, as well as $5.7 million in developer impact fees, to provide $130 million in improvements for the district.

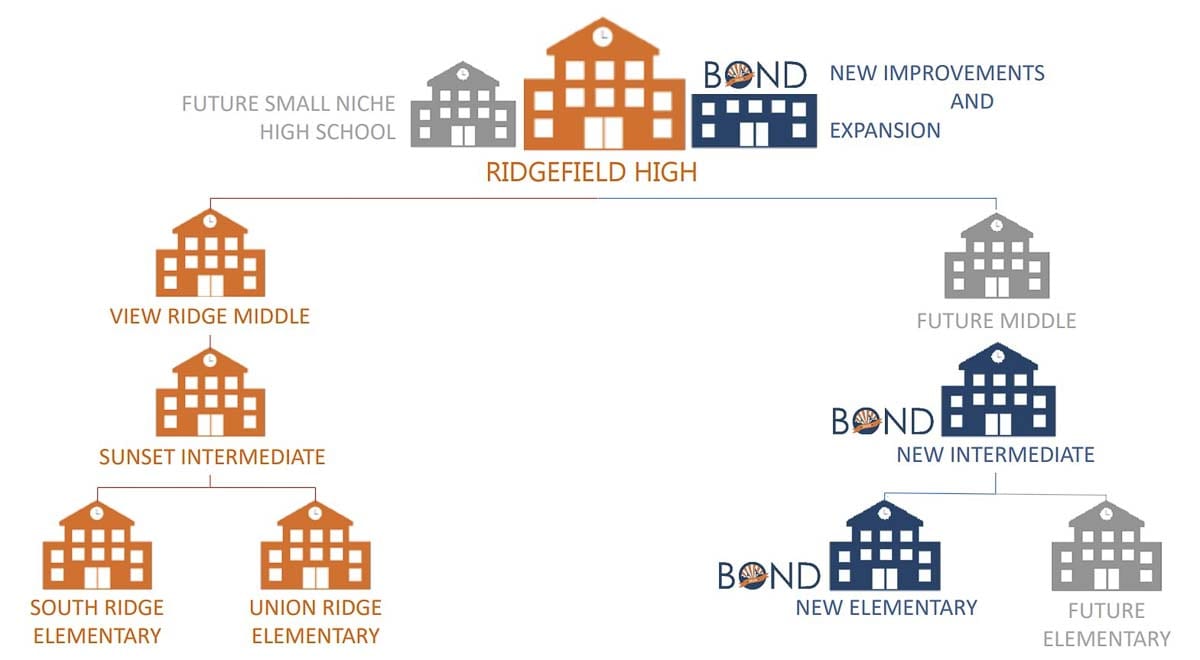

In addition to the previously planned K-4 elementary school and new vocational training for the high school, this year’s bond adds a grades 5-6 intermediate school, the first part of an eventual grades 5-8 campus, similar to the View Ridge/Sunset Ridge campus built with the 2017 bond. The money would also fund inclusive playgrounds at South Ridge and Union Ridge elementary schools, and other improvements.

As McCann puts it, the ask is bigger this time around because the needs continue to grow.

Ridgefield, which has been named Washington’s fastest growing city three times since 2015, is a rare school district that is continuing to see growth. District officials say they’ve welcomed almost 1,400 new students since 2014, and expect as many as 1,760 more by 2024.

“Joe Vance, one of our school board members, makes the point that if no other kid came into Ridgefield, from this point forward, we need a third elementary school already,” says McCann, pointing to data that shows the average size of an elementary school in Ridgefield is 690 students, by far the largest in Clark County.

“We’re not aspiring to have the smallest elementary schools,” McCann adds, “we value efficiency. We think there’s a sweet spot there. But it’s not at 700-plus.”

McCann also points out that, should the bond fail again, the needs will remain. The only thing that will change, he says, is that the price will go up.

“Same school, same design on the same site of land. The only difference between building it now in 2020, and building it last year in 2019, is that it’s going to cost about $4 million more,” says McCann, “because construction costs continue to escalate. That’s the inflationary factor that we’ve got to consider.”

Delaying the bond, McCann points out, also risks losing out on the chance to secure interest rates that are at 30-year lows right now for bonds. The district estimates securing the bond this year would save around half a percentage rate of interest, meaning millions of dollars in savings over the 21-year term of the bond.

If approved, the bond is expected to add approximately 97 cents per $1,000 to the property tax bill of a home in Ridgefield. For a $400,000 home that amounts to an increase of $388, or $32.33 per month.

“It’s not an insignificant number,” admits McCann before pointing out that the total property tax rate for 2019, in Ridgefield and within the school district, is currently lower than it was in 2013 by nearly $2.00 per thousand for most houses.

“Just in the six years that I’ve been superintendent, assessed valuation in the district has grown by about $1.5 billion,” says McCann. “There’s an increase in our property, but a lot of that’s coming from new property annually coming on.”

With the addition of the bond, and the 30 cents of state property tax increase coming back in, the district estimates the 2020 tax rate will remain below 2018 levels by around 36 cents (per thousand) in the county, and 31 cents in the city.

The increases would move school tax rates in Ridgefield from middle of the pack in Clark County, to third overall, behind Camas and La Center.

Assuming passage of the bond, the district would be unable to run another bond until sometime in 2024 or, most likely, 2025, says McCann. The state prohibits districts from carrying debt beyond 5 percent of their total assessed value. The district expects that number to be around $3.96 billion in 2021, which would put their debt ceiling around $200 million.

The 2012 bond, which was $47 million, should be paid off by 2032, McCann says, with the $78 million 2017 bond completed in 2037.

McCann also said there are no plans to ask voters to increase their local maintenance and operations levy, which sits around $1.50 per thousand of assessed property value. The state bumped the limit up to $2.50 per thousand last year, but Ridgefield had already passed a levy at the previous cap. That levy currently expires in 2022.

Worst case scenarios

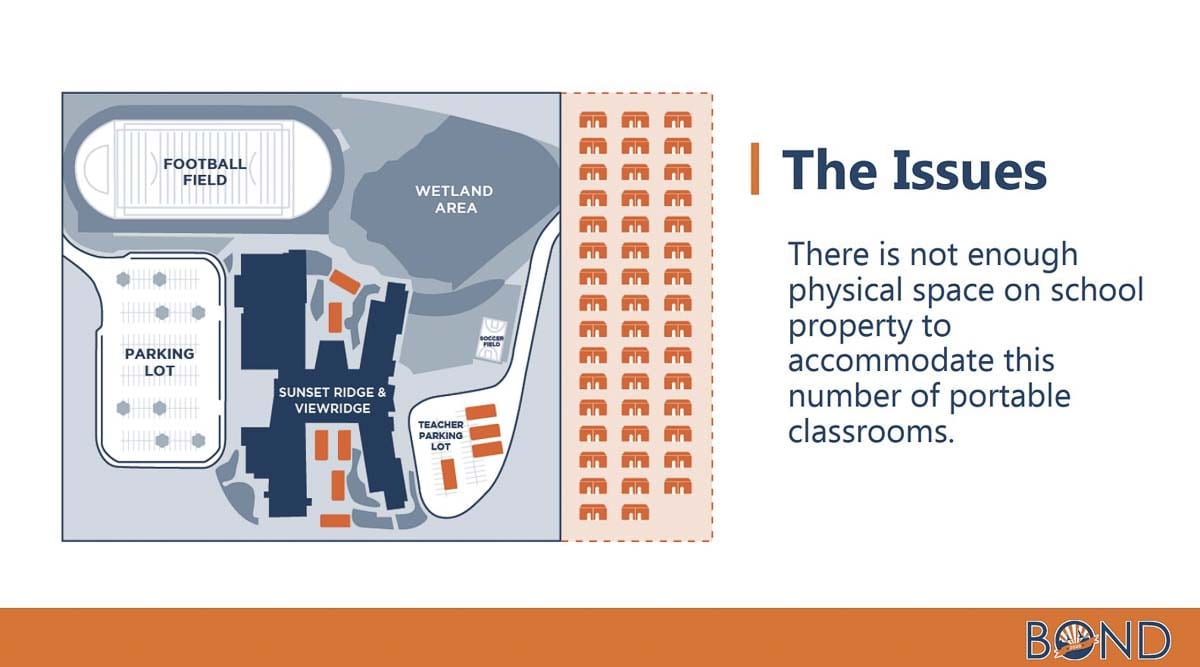

Should voters again decline to pass the bond, McCann says the district would be forced to turn to portables in order to find classroom space for incoming students. In less than two full years of the View Ridge/Sunset Ridge campus being opened, the district has already moved two portables in to handle the extra load.

If forecasts of 1,760 new students in the next five years come true, McCann says, that would amount to a total of 57 new portables. And those aren’t exactly cheap.

Each portable costs around $466,000 to have built and installed, with the cost currently rising by 5-8 percent each year with construction costs. That doesn’t account for the fact that the district currently doesn’t have the land to house all those portables, and would need to purchase more property, and build parking space and frontage for all of them.

Another option would be converting existing space, such as libraries, the black box theater, multi-purpose rooms, and common space into classrooms. McCann says that would create a whole slew of new problems, and run counter to the number one reason many people move to Ridgefield, which is for its highly rated school system.

An even more radical idea floated was to run a split-day school, with two shifts. While that would effectively double the district’s square footage, McCann says, it would create staffing problems, and leave many parents scrambling to figure out how to adjust schedules when school either starts at 6 a.m., or ends well into the evening.

McCann says his worst nightmare if the bond fails to pass is that they have to adopt some of these more draconian measures, and people who moved to Ridgefield for the great schools, and educators who declined other offers to come there, become disheartened and disenfranchised.

“This is the bargain on the west coast. This is the place to be,” he says. “Every place else is either too expensive or it’s already been formed. Ridgefield is still kind of charting its course. We’re finding out what we can be as a community, and the potential is unlimited.”