The district is touting past bond projects in urging support for a new $77 million bond this coming February

RIDGEFIELD — In February of 2017, 68 percent of Ridgefield voters approved a $78 million building bond for schools. Now the district is hoping for a repeat next February, introducing a new $77 million building bond to add a new K-4 school, expand the high school, and improve a number of elective programs.

Despite Ridgefield’s history of supporting schools, the district knows it may be more of an uphill battle this time around. Homeowners in 2018 saw property taxes jump as a result of the state legislature’s funding package for basic education. But one-time property tax relief in 2019, and the result of capped local enrichment levies, could favor Ridgefield schools this time around.

The 2017 bond totaled $94 million, including $16 million in state matching funds, and helped build the new 5-8 grade campus, provide security upgrades at Union Ridge and South Ridge elementary schools, and a new building on the high school campus.

“If you add everything we’ve done, and the city’s work on the Ridgefield Outdoor Recreation Complex, there’ll have been about $125 million of improvements,” says Ridgefield Superintendent Nathan McCann. “And that’s pretty substantial in just a two-year period.”

In addition to housing a slate of expanded community education programs, the former View Ridge Middle School building is being turned into a home for school administration, as well as a civic center housing a number of city departments. It will also be home to the Ridgefield Chamber of Commerce, Ridgefield Main Street, and a cafe run by Kilobytes, which works with transitional special needs students to give them job skills experience. It will also be home to a proper meeting place for Ridgefield City Council, which currently uses the community center for public meetings.

“By the time this two years has rolled by in February of ’19 we’ll have everything except for the high school, which be well moving towards completion at that point, completed on that bond program,” says McCann.

It’s that kind of quick-moving work that McCann hopes the community will look at when deciding whether or not to vote for the new bond next year.

“We want to be known as a town that is nimble and flexible, and able to move very quickly to get the important work done, and done first,” says McCann.

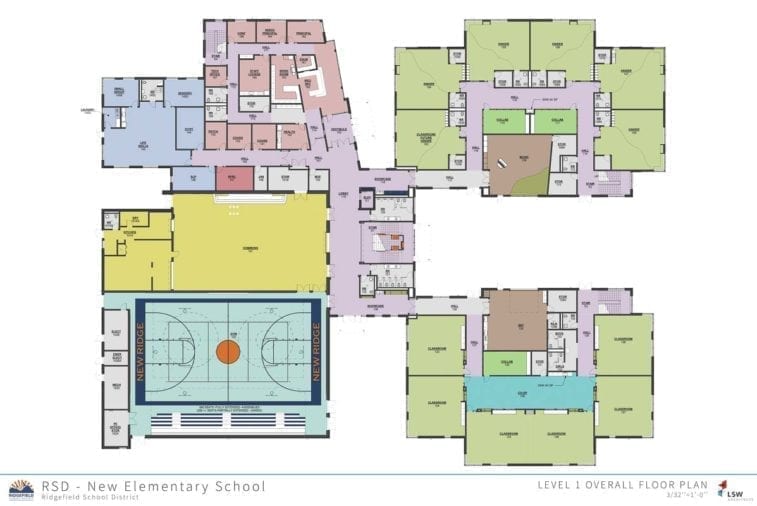

At $77 million, the bond is expected to add around $2.25 per month to the tax bill of a $300,000 home in Ridgefield. It would be matched by $15 million in state funding. That would be used to build a new K-4 elementary school, and further expand the high school campus.

“Certainly with the projected growth, 1,422 new students — new students — in the next four years, the schools and the additional expansions at the secondary level can’t come soon enough,” says McCann.

The Ridgefield school board, along with their six-member Capital Facilities Advisory Committee (CFAC), have chosen to take a bold approach, front-funding much of the design work ahead of putting building bonds in front of voters.

“That same focus on doing it right and doing it quickly will happen with the ’19 bond,” says McCann. “We’re already well through the design process on that elementary school, with the idea that we can go ahead and break ground in May of ’19 with a successful passage in February.”

McCann adds that they’ve spent around $1.5 million already to do design work on the new school, though more will need to be spent if the bond is approved.

“I think it’s also been the board’s way of reminding the community of the urgency and the importance of this work,” says McCann.

Improved vocations programs

The bond would also fund a long-overdue upgrade of Ridgefield High School’s shop classes, including metal and woodworking.

McCann says his push to upgrade the skilled trades programs comes partly from conversations with the many contractors he’s worked with over the past several years as the district has built its new schools.

“Everything I hear from our construction contractors is that they can’t get enough skilled labor,” says McCann. “There are great jobs waiting for kids, and you can see that there are kids who want to be doing this work and can make a good living doing this work.”

Past emphasis on four-year degrees, along with schools focusing more on Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) classes, meant that a lot of districts cut trade programs. The shortage in skilled tradespeople left after the economic recovery could now take generations to fill.

“This isn’t stuff that can be outsourced either,” says McCann. “This isn’t work that’s going to happen in India or China someday. I need it done in Ridgefield, it has to be done in Ridgefield.”

Chris Shipp, a 2002 Ridgefield graduate now leads the program. “Everything was old then. It’s 15 years later and literally nothing’s changed,” he says.

To be accurate, a few things have changed. But most of the newer equipment Shipp’s students work with actually came from him. Shipp says he has donated about $30,000 worth of his own equipment.

It’s not just an issue of getting equipment. In some cases the district has gotten updated equipment, but the building is too old to actually hook them up.

“We got a plasma cutter donated by AIG, who’s the steel company that did all the steel work on the middle school,” Shipp says. “They donated it last December. We were trying to have it hooked up by Christmas last year and we’re still waiting for electrical on that one.”

Dealing with growth

Perhaps nowhere else in Clark County feels that pinch as much as Ridgefield. Over the past decade they have ranked at or near the top of the fastest growing cities in the state. That growth is evidenced in new neighborhoods popping up, along with a number of massive construction projects slated for The Junction near I-5 over the next decade.

That growth has been the topic of much discussion within Ridgefield, which clings to its small town identity amidst a decade of explosive growth. While McCann says the district is neither pro nor anti-growth, it has allowed them to expand a number of programs that didn’t exist before.

“I can point across the board at programming and extracurricular opportunities that are available to our kids that flat out didn’t exist a few years ago,” McCann says, “and part of that is because of the growth.”

If voters approve the new building bond in February, it will represent the third phase of a four-pronged approach to dealing with the explosive student population growth the district has experienced in recent years. Phase Four would allow for the district to potentially address further overcrowding issues with a new K-4 school, 5-6 and 7-8 buildings and a small specialty or alternative high school.