‘Too early’ to know if $1.25 billion proposal will meet congestion relief goals

The Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) last week questioned the viability of a $1.25 billion I-5 Rose Quarter project to move forward with the wider freeway covers negotiated by Gov. Kate Brown last month. The “Hybrid 3” covers will add to the cost of the project, plus will require a delay in the project of perhaps a year.Those highway covers are part of a “restorative justice” effort, but might not be funded by constitutionally protected transportation funds.

Commissioner Sharon Smith asked if the Hybrid 3 design will achieve the congestion relief goals. Project Director Megan Channell responded: “It is too early to have all of the kind of final and detailed technical analysis answers for what the impacts of that are.”

Commissioners expressed serious concerns about the increase in costs — an $800 million shortfall from the $450 million the Oregon legislature allocated in 2017. “Where will the money come from,” asked Smith.

Commissioner Julie Brown asked if spending $400 to $500 million for 1.73 acres of a highway cap is really getting the value the Albina community wants? She questioned the viability of the project.

Many Southwest Washington citizens are concerned about tolling. During the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) battle it was estimated Washington residents would pay up to 60 percent of the bridge tolls. The $8 tolls were necessary because the project was going to borrow roughly $1.5 billion of the $3.5 billion project’s estimated cost.

That $800 million Rose Quarter funding shortfall only allows for highway covers that would support buildings two-to-three stories tall. Members of the Historic Albina Advisory Board (HAAB) have pushed for covers that would support buildings up to six stories, which could possibly raise the price tag to $1.75 billion according to ODOT’s Megan Channell.

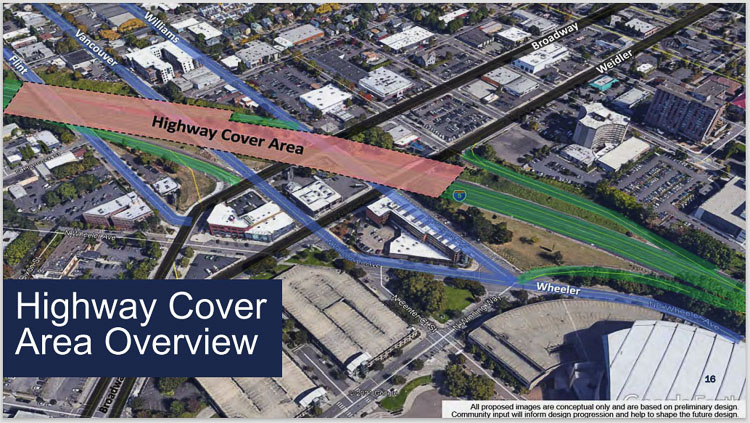

The Hybrid 3 cover was a compromise solution negotiated by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, announced in early August. It narrowed the I-5 inside shoulders in the project area from 12 feet to 4 feet. It relocated southbound on/off ramps to Winning Way at the Moda Center. It eliminated the separate bike/pedestrian bridge, in favor of the bigger cover.

Citizen testimony lasted almost an hour. Much of the comments centered around either killing the project because it expands the width of the freeway, or due to climate change concerns. Those speaking in support addressed the restorative justice for Portland’s minority community, and labor union activists supporting job creation.

“In the space of a little less than four years, the cost of this project has ballooned by a factor of almost three,” said Joe Cortright of No More Freeways. “It was sold as a $450 million project, which is now approximately a $1.2 billion project before you move a shovel of earth. This project will consume resources that could be used for all kinds of transportation projects and all kinds of employment creation in the state.”

Investing over a billion dollars to facilitate more car traffic is exactly the wrong thing to be doing now, he told the Commission. Cortright and others believe the project should not widen the freeway for a variety of reasons, including climate change. They want a full NEPA environmental analysis done, which they know would delay the project.

The OTC also received an update on Oregon’s tolling plans, which staff called the Regional Mobility Pricing Project. Tolls would begin at the Boone Bridge on the south end of Wilsonville, and run all the way to the interchange at N. Columbia Boulevard. That’s about 2.5 miles south of the state line.

However the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) Administrator Greg Johnson says tolls must be used to pay for the replacement of the Interstate Bridge. This will necessitate tolling beginning at the north end of the bridge, at a minimum.

On I-205, tolls would start south of the Glenn Jackson Bridge and continue down to where I-5 and I-205 meet. ODOT staff spoke about it being a “complete tolling system.”

Rose Quarter discussion

Staff briefed the OTC about the costs of the revised Rose Quarter project, pointing out a significant funding shortfall. The Oregon legislature created the original project in 2017, as part of a $5.3 billion transportation package. That bill also included language directing ODOT to “study” tolling beginning at the border with Washington.

“We will match those costs with potential sources of funding,” said Travis Brower, ODOT’s director of Revenue, Finance, and Compliance. “Those sources include the $30 million in annual funding available for urban mobility projects under HB2017 as well as other funding sources such as toll revenue, federal formula funds and federal discretionary grants. The finance plan will also look at how we can use financing mechanisms, such as bonding and short term borrowing to generate the resources upfront that we need to build the project.”

“There’s no way for you to move forward now without actively considering tolling,” said Cortright. “The governor instructed you more than a year and a half ago to include tolling in your analysis and you did not do so. It is long past time to consider what the effects of tolling would be,” he said, referring to reduced demand for roads due to the price being charged.

Brower mentioned that the Oregon Constitution might not allow for transportation money (like gas taxes, car tabs, and tolling) to be used for the restorative justice highway covers. ODOT will consult with the Oregon Department of Justice on how to apply this restriction on the Rose Quarter project.

Commissioner Smith initially sought clarification on the value of the investment. “In essence, what we get is approximately two acres of highway cover that could be developed with two-to-three story buildings,” she said. “And the cost of those two acres is roughly $400 million dollars.”

She understands the desire to “reknit” the Albina neighborhood. She noted the original decision to locate I-5 was not simply ODOT’s, but the entire community, including the city of Portland, Multnomah County, and the neighborhoods around the whole area. OTC Vice Chair Alando Simpson later reiterated that point.

Historians note that I-5 generally follows the old US 99 route created in the 1920’s which followed the Pacific Highway.

“When we look at a finance plan to embark on restorative justice, it seems to me that ODOT shouldn’t be the only entity at the table helping to right that wrong,” Smith said. She wanted all parties to be part of the solution, including the funding.

Brower responded that they can certainly explore the potential of a contribution from the city of Portland and from other players within the region, including private sector partners, if they received that direction from the OTC.

At a joint meeting of the project’s Executive Steering Committee (ESC), Community Oversight Advisory Committee (COAC) and the HAAB last month, Jana Jarvis, head of the Oregon Trucking Association made a similar point. “We’re talking a lot about restorative justice here, but those decisions were made decades ago and they certainly weren’t made by truckers or passenger vehicle owners.”

Simpson weighed in, expressing concern about the price. He chaired the ESC and was also part of the HAAB meetings. “One of the things that I felt a fiduciary responsibility for in that position, was to make sure that the project stayed on budget and on schedule,” he said.

Simpson was asked for examples of those “stay on budget” discussions and has not responded..

At a May 24 joint meeting of the HAAB and COAC, Simpson said: “there’s a big elephant in the room. That elephant comes with a big bag of cash.”

“I’m now trying to think about how we kind of put some, some buffers, some boundaries on where we’re at now,” Simpson said. “Because I would assume there’s got to be some discomfort with numbers this large. He noted the numbers — 1.73 acres added for $455 million dollars yields $6,037 per square foot. “And that’s just for land,” he exclaimed.

Simpson didn’t speak against spending the money, but about ensuring there is a reasonable benefit. “It is my fiduciary responsibility and obligation to again, ensure that there is going to be a justifiable return on investment if we make a capital investment of that scale,” he said.

Brower mentioned the federal infrastructure package (not yet passed by Congress) had $1 billion nationwide for programs of a restorative justice nature. Oregon’s piece of that pie might be in a “very optimistic range of $80 to $100 million,” he said.

Commissioner Julie Brown weighed in. “I’m always going to ask how are we going to pay for something?” She understands and appreciates the activities that can occur on top of the cover and how it might help with restorative justice. “I’m a stickler on making sure that the state of Oregon takes into consideration all these projects that will benefit everyone, all Oregonians,” she said.

The Rose Quarter project is “probably one of the biggest costs of a transportation project that has ever happened in the history of Oregon,” she said. “I would be remiss if I didn’t put the brakes on a little bit and and push back a little bit and say, this is great, but we need to find a way to pay for this.”

Brown wants to see financial commitments from the city of Portland, Metro, and the people who live in the community contribute. She mentioned Congressman Peter DeFazio and Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley. “We have to be realistic of what we’re going to get from the federal government,” she said.

Commissioners Smith and Simpson echoed Brown’s expectations that all local stakeholders will financially contribute to the project.

OTC Chair Robert Van Brocklin talked about an effort between 2015 and 2017, where the OTC held listening sessions around the state. “What’s the biggest transportation problem in Oregon? What’s the most critical problem in state transportation? Time and time again, they heard all over the state — Portland congestion.”

He mentioned that simultaneous with the passage of HB2017, there was conversation about the opportunity to do something good on top of the freeway. Yet he too is concerned about finding the money to pay for the project. “I think an open-ended search for money is not realistic,” he said.

Van Brocklin wants a funding plan, and to evaluate whether that plan is based in reality. Are there realistic sources of money available to pay for this project which is “unique and different than all other projects.” But he reminded the commission they were given “broad authority” by the legislature to toll other roads around the state, implying that tolling could make up part of the funding shortfall.

Where’s the value?

Smith responded that a lot of things have changed since 2017, from concerns about the climate to highway safety and the resiliency of the system, to racial justice. “I just wonder if we were to ask the question of the legislature, or the state, or the citizens, do you want to spend $1.5 billion on a Rose Quarter project,” she asked. “Is that the best use of our funds right now? And I don’t know if the answer is yes.”

“We have had so much change, that I think it’s important to just question the viability of the project,” Smith said.

“I don’t presume to tell the Albina community what they should want,” Brown said. “It’s a rhetorical question, does it make sense for ODOT and the rest of the jurisdictions because we can’t do it by ourselves, to spend $400 to $500 million, for 1.73 acres of a highway cap? Is that really getting the value that you want?”

“We can do a lot of things in mitigation,” Brown said, but mentioned the constitutional limits on what the OTC can spend money on. “Could we spend that kind of money on other things and do more for the community?”

She asked for those kinds of questions to be brought to the table, They’re important questions. Van Brocklin agreed.

Van Brocklin reviewed the history of the project and cost changes. He asked ODOT staff to come back to the commission with a funding plan in either December or January, believing they will know whether or not Congress has passed a transportation plan and how much might be available for the project.

Simpson brought up the fact that several groups walked away from the discussions and process over restorative justice concerns. These were the Albina Vision Trust, the city of Portland, Mayor Ted Wheeler; Multnomah County and Metro. He now wants to see them step up for funding. “How much are they willing to invest in restorative justice,” he asked.

“The last thing I want to see is a big slab of concrete that doesn’t have anything on it,” he said.

Commissioner Smith asked if the Hybrid 3 design will achieve the congestion relief goals. Project Director Megan Channell responded. “It is too early to have all of the kind of final and detailed technical analysis answers for what the impacts of that are.”

Asked about narrowing the width by reducing the shoulders, Channell indicated they are reducing the “inside shoulders” (in the left lanes) in the design, but will see how that impacts congestion relief and safety goals.

Citizens might wonder how narrowing shoulders that are placed on highways expressly for safety reasons, can contribute to the overall safety level of the project.

Taxpayers might wonder how Oregon can afford $1.25 billion or more for the Rose Quarter project, a $700 million I-205 Abernethy Bridge project, a $3 billion to $5 billion Interstate Bridge project, and an estimated $5.1 billion for seismic upgrades and repairs to roads and bridges statewide.

And Southwest Washington citizens seem justified if they are worried about how much of those bills they will be paying, once Oregon implements tolls to drive on its metro area freeways. The OTC expects to coordinate with the Washington Transportation Commission by 2025 to set toll rates for the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program.

Want to kill something, form a committee. Want to kill something “real good”, form a bi-state committee.

This excellent report could be titled, “Oregon wants to add $800 MILLION in costs for Rose Quarter for overhead I-5 freeway covers as a restorative justice project, plans to toll drivers on I-5 and I-205 to pay for bloated project”

If the project doesn’t provide congestion relief, what is the point?

Travel justice demands the freeway be widened. Cover it later if you’re so inclined.

Thank you for that clear and insightful summary! I live on Hayden Island so I’m familiar with congestion. A roof on I-5 doesn’t seem like it provides any help.

I feel that rapid transit is an absolute requirement to reduce auto pollution. Tolls would help by making single occupant travel expensive on a daily basis. I also think that Gasoline is much too cheap and should be much higher to reduce pollution and slow CLIMATE CHANGE. Even when the forests are gone (burned out) vegetation growth will fuel grass and hedge fires that destroy habitats, wildlife environments and house. This will soon solve immigration problems by making life in the USA hell.

To act sanely, we should NOT strive to make commuting easier.

Dennis —

If you truly believe “we should NOT strive to make commuting easier”, are you against the entire project?