Understanding the wildland fires of today by looking at one of the largest in our region’s history

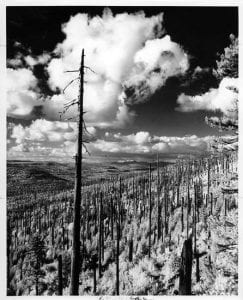

YACOLT — It’s been nearly 120 years, but the memories have lost none of their potency. Walking atop Bell Mountain, or down a trail in many surrounding state forests, it may be hard to tell, but the entirety of northeastern Clark County was once a fierce inferno for three days.

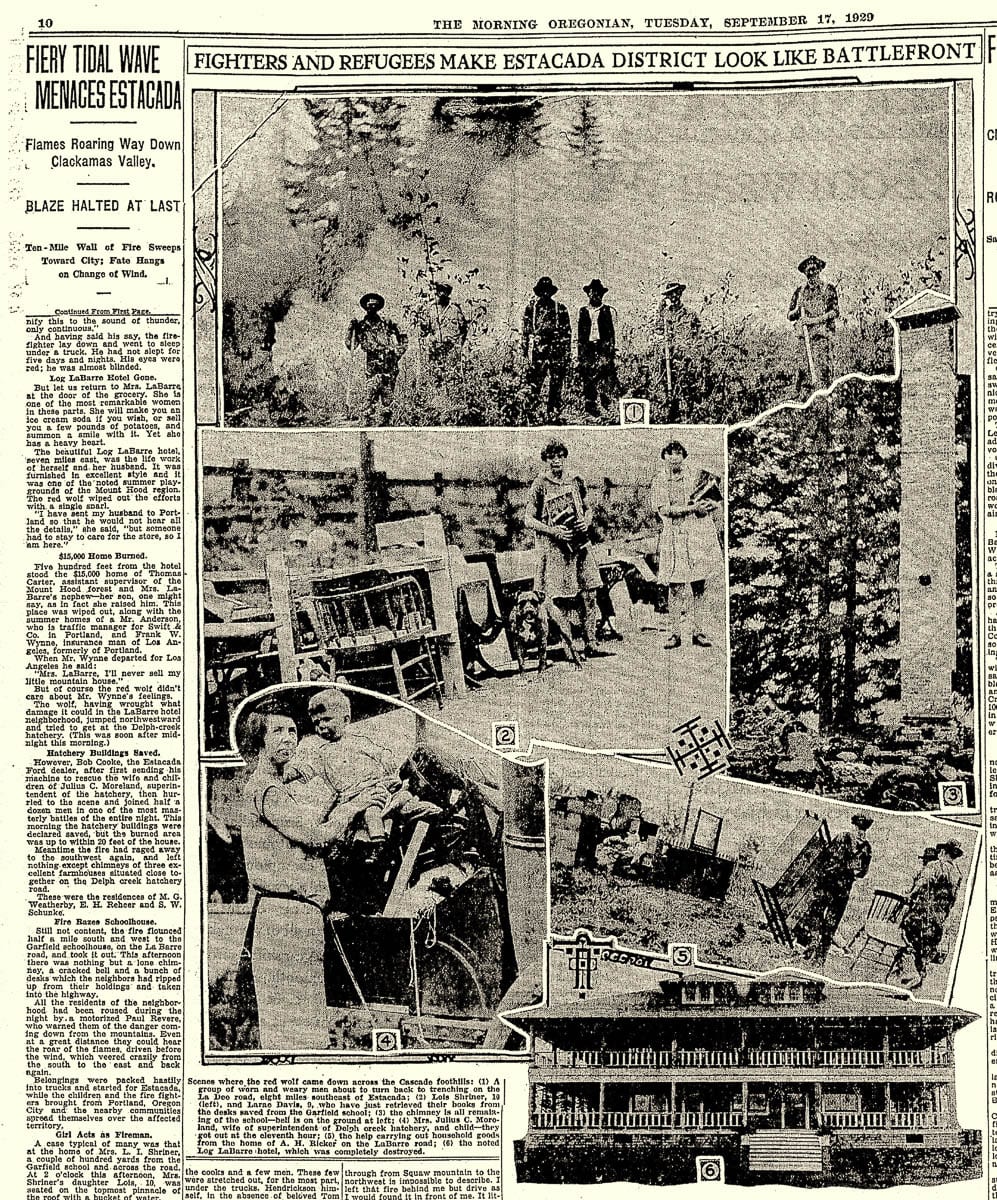

The Yacolt Burn, as it is commonly referred to, was a massive wildland fire from Sept. 11-13, 1902. The fire covered large swaths of Clark, Cowlitz and Skamania counties as well as areas in northern Oregon. The blaze devoured nearly a quarter of a million acres of forest and claimed the lives of 38 people.

When accounting for inflation, the estimated damage from the burn in destruction of forest land and private property, comes close to $1 billion. Some 400,000 additional acres burned simultaneously that year across Washington state.

The Big Hollow Fire, which recently burned southeast of Cougar and is only now nearly extinguished, only burned 25,000 acres and took no lives or property, but was influenced by similar weather and environment to the Yacolt Burn.

How such a massive fire came to be so long ago has more ties to the present that is first apparent. The fire’s cause and effect are directly linked to Forest Service policies that have endured for decades, as well as weather patterns that are notorious for spurring fires.

Voices of yesterday

The manner of life for those living in around Yacolt in 1902, may be perhaps, so different from that of today, it is difficult to explain without firsthand knowledge. Thankfully, the Clark County Historical Museum (CCHM), in collaboration with Washington State University Vancouver, has preserved the voices of the past.

Grace Palmer and her son Martin lived in the area at the time of the Yacolt Burn, as well as the several fires that followed it. Driving in the mountain foothills of areas like Dole Valley in their Model T Ford, they witnessed first hand the effect of the fires.

In 1972, Mary Carson and Jean Holroyd of the CCHM interviewed the Palmers with a tape recorder. The first thing they remembered was the smoke and the sun.

“By noon, it was so dark, that you just couldn’t see your hand in front of you,” Grace said. “It was just a thick darkness. And people became very frightened, and thought that this was the end of the world. That’s all they could think of.”

The darkness blocked out the sun across much of the region, with smoke affecting cities as far away as Seattle and Astoria. Vast numbers of people were soon evacuated by the military. A steamboat sailing the Columbia River had to use a search light in the middle of the day, according to history collected by David Wilma of HistoryLink.org.

“In the fall in those days, every little farmer had a patch of brush that he had burned down or cut down,” Grace said. “And then when it was real hot, they set this a fire. So everybody was burning at the same time. And it made smoke from all directions, you know. And it didn’t take much extra to make it real dark.”

“It was when I was a small feller and we were in a Model T Ford coupe, and there was fire all around and we went out into what you call Dole Valley,” Martin said. “I remember that it had a candlestick effect that these big tall snags, which were the remnants of the fire many years before, where trunks usually three to four or five feet across, sticking anywhere from 50 to 150 feet in the air. They caught fire at the tops and spread across the things, and as we were driving along in the Model T Ford, you’d still see the flaming at the tops of the trunk like candles.”

Margretha J. Jarvis also lived in Clark County at the time of the Yacolt Burn. In 1975, Louise Fraiser of the CCHM interviewed her via tape recording. Her father, a german immigrant, founded a sawmill in Yacolt Valley to process timber cut there.

“All over the Yacolt Valley and the hills surrounding were very heavily wooded,” Margretha said. “At the time we first went there, practically the whole Yacolt flat valley was timbered. Every year it seems as though there was a forest fire. There was [also] a very bad one in 1910. That’s when the fires really did come down to the town.”

The beginning of a mismanaged era

Horace Wetherall was the first to spot the Yacolt Burn. He did nothing. Prior to the burn, the lone forest ranger at Mt. Rainier Forest Reserve had been reprimanded for employing a fire crew. He did not wish to be punished again, according to Wilma.

As the Yacolt Burn grew in size, no attempt was made to quench it. It was permitted to rage, until being put out by rains after three days. Instead of fighting the flames, crews and military personnel worked to evacuate those in harm’s way.

While this may sound like relative insanity by today’s standards, this method, (if it can be called a method), is closer than constantly fighting fire is to what forest scientists call ‘’healthy.’’

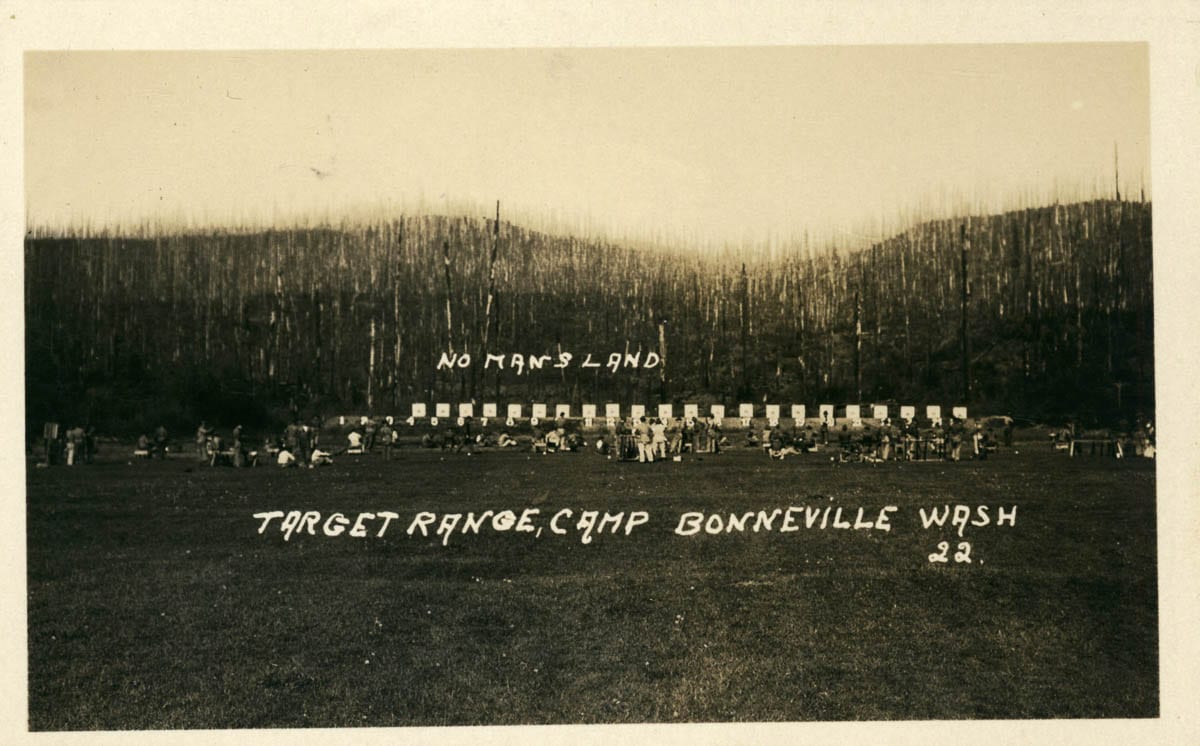

For better or worse, the Yacolt Burn was one of many vast fires across the western United States from the late 1800s into the late 1920s that propelled american forest management into an era of total suppression.

The 1910 fires, Margretha referred to, are better known as ‘The Big Blowup.’ This event consisted of over 1,700 massive wildfires across Montana, Idaho and Washington that burned more than 3 million acres. Hurricane force winds in August of that year, whipped many fires into hellish scenes that tore rapidly across forests.

The devastation led three men who fought the fires, William Greeley, Robert Stuart, and Ferdinand Silcox, to change the doctrine of the National Forest Service as they each served as chief through 1938.

It was known as the 10 a.m. Policy. No matter the size, no matter the location, no matter the conditions, every fire that sprouted in the United States would be suppressed and extinguished by 10 a.m. the following day from which it was discovered.

It was a bold, and culture-altering move. The country’s affinity with the brave firefighters, later known as hotshots, and smokejumpers rose in the decades to come. Forests were never allowed to burn, and subsequently built up heavy ground cover and dead trees. Many scientists now believe, the fires of then that prompted such recourse, set the stage for the fires of today.

Above information sourced from David Wilma, PBS’s Nova and the Forest History Society

Parallel image, only in color

To allow a wildland fire to simply burn and clear the forest of debris, is a concept that began to take root in the late 1980s and early 1990s; decades after the Yacolt Burn.

Such thinking has led to experimentation in plots of forests in places like Montana, where controlled burns are applied to one area, while the adjacent is prevented from burning. The health of the forests allowed to burn is substantially better, according to Forest Service Fire Ecologist Sharon Hood.

Allowing fires to burn, however, is often impossible with the substantial growth of housing into what is known as the Wildland Urban Interface. In northern Clark County, this is more evident than ever, as more residents move to the woods.

Ironically, scientists and firefighting agencies from California to Washington, have observed substantial pushback from so-called ‘enlightened forest management;’ chiefly prescribed burns and forest thinning.

Such methods are often expensive and in states like Washington, the Department of Natural Resources is stretched thin on the issue of firefighting and prevention, according to recent statements from Commissioner of Public Lands, Hillary Franz.

Perhaps more ironically, large and devastating fires such as the Yacolt Burn or ‘The Big Blowup’ being prevented, may now be leading to more such events in a higher frequency; a situation leaving many in the field asking, “Can we learn from our past?”

Above information sourced from PBS’s Nova: Inside the Megafire