Tens, perhaps hundreds of billions needed for ODOT Westside Mobility Improvements

John Ley

for Clark County Today

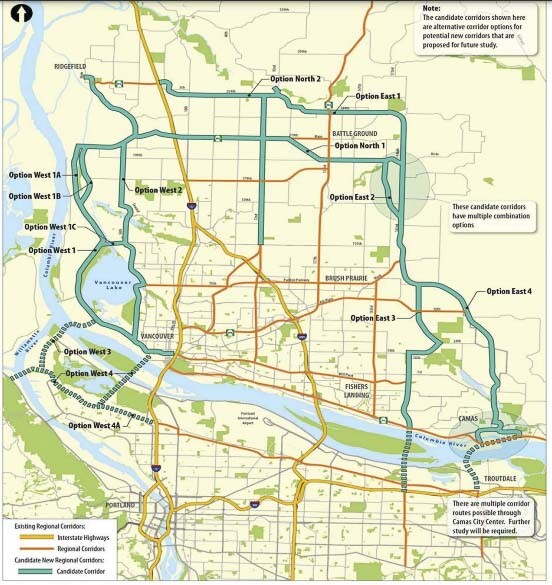

Since the failure of the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) in 2013 when the Washington State Senate refused to fund $450 million for the “light rail project in search of a bridge,” area citizens have hoped for a project that actually delivered traffic congestion relief in Southwest Washington. People didn’t understand why a third bridge and crossing wasn’t under consideration, adding vehicle capacity to the region. It’s been over 40 years since a new transportation corridor was built – I-205 and the Glenn Jackson Bridge.

The current Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBR) projects morning travel times will more than double by 2045, to 60 minutes to go from Salmon Creek in Clark County to the Fremont Bridge in Portland. Fully half of rush hour traffic will be traveling zero to 20 miles per hour. More people than ever are choosing to use their privately owned vehicles for travel.

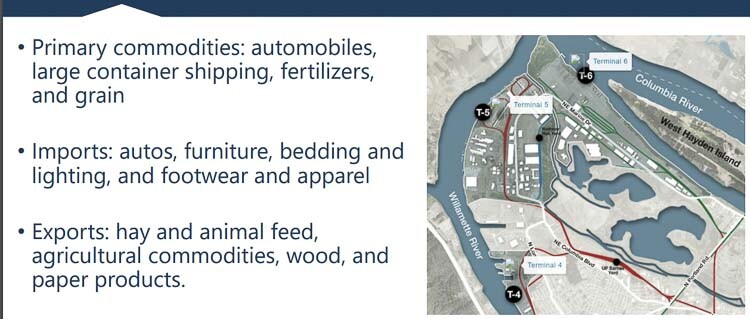

In 2008, the Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council (RTC) released its “Visioning Study” which identified the need for two new bridges and transportation corridors. The study provided two options for a bridge west of I-5. Both connect the Port of Vancouver with the Port of Portland potentially removing many 18-wheel trucks off I-5. This could have been part of the CRC “options” considered and subsequent solution.

With the 2019 signing of a Memorandum of Intent, Governors Jay Inslee and Kate Brown restarted both states’ efforts to resume a project. “We do not have an option,” said Inslee. “This bridge has to be replaced.”

“It’s high time that we address the congestion between our two states and invest in a bridge that will withstand the test of time,” said Oregon Governor Kate Brown. While mentioning congestion, Brown said replacing the seismically unsafe span with one that is more earthquake friendly is her top priority, followed by the inclusion of some form of high-capacity mass transit.

Fast forward four years, and the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) and Metro have been working on a Westside Mobility Improvement Study (WMIS) for at least two years. They assembled interested parties that began “engagement” in January 2022. A steering committee began meeting in May. It consisted of ODOT, Metro, TriMet, Washington and Multnomah County Commissions, Beaverton, Hillsboro, Portland cities, the Port of Portland and several business and community interest groups.

A seven-page multibillion dollar list of components was presented for discussion and consideration to the WMIS committee on Nov. 2. There were no specific costs; merely one referring to five dollar signs. Presumably, five ($$$$$) equates to “over a billion dollars.”

This is of specific interest to Clark County citizens because there is a vehicle tunnel under the Portland west hills, connecting US 26 to US 30. That then connects to a new bridge over the Willamette River, connecting to three Port of Portland terminals. The Portland area already has a dozen bridges over the Willamette River. The WMIS package of projects wants to add one more.

The vehicle tunnel and new bridge would appear to make a logical western bridge connection over the Columbia River. It would connect the Port of Portland with the Port of Vancouver.

It could have been part of the IBR discussions, but Greg Johnson and the IBR team have repeatedly said there is “no plan” in regional transportation plans (RTC or Metro) for a third bridge over the Columbia River. However, it has now been revealed that for over two years, Oregon has been planning for the Oregon half of a possible new transportation corridor.

There’s been no mention of this project by Oregon legislators on the 16-member Bi-State Bridge Committee providing oversight of the IBR. Rep. Susan McLain, Sen. Chris Gorsek and others remained silent when Washington Sen. Lynda Wilson (17th District) mentioned the new bridge and connection at the Dec. 15 meeting.

Metro President Lynn Peterson sits on the IBR’s Executive Steering Group along with ODOT’s Kris Strikler and Port of Portland’s Curtis Robinhold. There was no mention of the new transportation corridor by any of these people.

Northern Connector

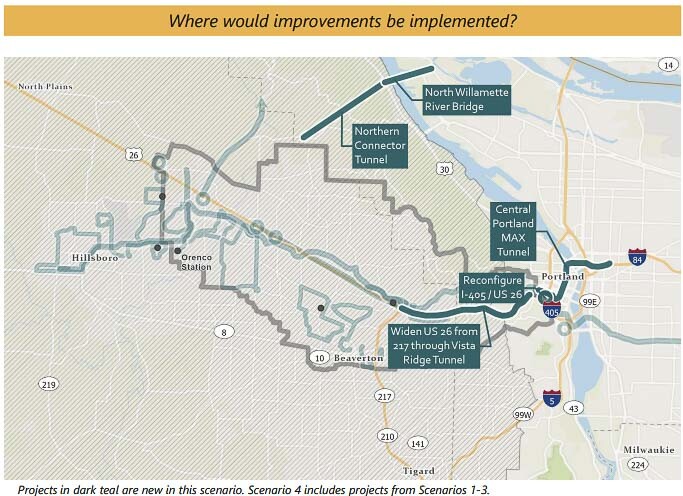

A map of the possible westside transportation projects reveals something stunning, at least to many observers. The Northern Connector runs basically from US 26 through a tunnel under the west hills to US 30. Then a new bridge over the Willamette River connects US 30 with the Port of Portland terminals 4, 5 and 6. Additionally, the project ties into a Marine Drive connection to the Portland Airport and beyond, according to a separate graphic.

A 2015 strike caused major shipping companies to stop using the Port of Portland. This put thousands of 18-wheel trucks on I-5 annually, adding to vehicle congestion on interstate freeways. Hanjin Shipping and Hapag-Lloyd both ceased operations to Portland. This emphasized the need for alternate transportation corridors to be created.

The Northern Connector would allow freight haulers and people in their cars to access US 30, traveling north and use the Longview Bridge to access I-5. Freight haulers could also pick up loads at the Port and access US 26 in a more direct route, avoiding the congested Vista Ridge Tunnel.

It would also reduce vehicles being forced to use the three-lane Vista Ridge Tunnel and downtown Portland, in order to get to the Portland Airport or travel north on I-5. That is the second most congested point on Oregon highways according to ODOT. It would provide alternative routes and redundancy in the transportation system.

According to a flier, Washington County has roughly 97,000 non-resident workers commute into the study area daily, while 64,000 residents commute outside the study area for work. Those 161,000 people are potentially making over 320,000 daily trips if they work outside the home. Only 27,000 people live and work in the county.

Alternatives over the decades

Multiple alternative transportation corridors have been envisioned over the years. These include a 2017 proposal by Oregon Rep. Rich Vial, who offered two possible routes for a westside bypass, one of which closely mirrors the Northern Connector. An earlier Oregon plan, to be completed by 1990 shows both the I-205 and a western freeway bypass.

A 1979 Clark County Comprehensive Plan map shows SR-501 in west Vancouver as a bypass. It recommended using the 179th St. corridor and SR-501 to route traffic over a Columbia River bridge connecting near Scappoose. The 2008 RTC Visioning Study provided two options at this location that are imitated by this Northern Connector proposal. Transportation agencies Metro and RTC simply need to tie the two together.

Perhaps 50 or more years later, the Northern Connector will be the beginning of constructing a route envisioned for bypassing downtown Portland. All that appears to be needed is to adopt the plan and add a bridge over the Columbia River. This would connect the two ports and then run north to connect to I-5 in north Clark County.

The Washington State Transportation Commission (WSTC) recently voted on a city of Ridgefield request to eliminate SR-501 as a state highway in west Clark County. Why would eliminating this very logical connection for a freight bypass be proposed? The Washington State Legislature could kill it in the upcoming 2024 session.

IBR connections

Citizens might wonder why this wasn’t considered by Greg Johnson’s IBR team? After all, the 5-mile bridge influence area could include a connection to the Port of Portland facilities at terminals 4, 5 and 6.

The likely answer lies in an Oregon Supreme Court Justices ruling that the failed CRC was nothing more than “a light rail project in search of a bridge.’ It also lies in the remarks of the two governors signing the Memorandum of Intent. The second “top priority” verbalized by Brown was high capacity transit, which indicates a desire for a needed platform for light rail being extended into Clark County.

Over the past four years, the IBR team has chosen to keep the exact same Purpose and Need statement used by the CRC. They have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars discarding an immersed tube tunnel option as well as a third bridge, either next to the current structures or to the west connecting the ports and adding vehicle capacity to the entire transportation system..

The IBR team has consistently ignored citizen’s top priority, a bridge and transportation system that reduced traffic congestion and saved people time. This is in spite of the Pemco survey showing 94 percent of people prefer to use their private vehicles for transportation. and IBR surveys show saving time is the top priority. IBR community surveys show 7 of 10 people want to save time and reduce congestion; while Southwest Washington residents increase that priority to 8 of 10 people.

Instead, transit ridership estimates have been created reporting 26,000 to 33,000 transit riders a day in 2045 for the I-5 corridor. That appears to conflict with reality. Currently, C-TRAN express buses carry less than 1,000 people a day over both I-5 and I-205 bridges. One legislator told Johnson: “if I take those numbers to my constituents, I’m f***ed!”

Johnson’s team stands by those numbers, presumably to justify a $2 billion, 3-mile MAX light rail extension into Clark County. This is in spite of Clark County voters rejecting light rail three times at the polls. Oregon voters rejected a new light rail line in 2020.

The US Coast Guard is currently balking at the IBR’s proposed “bridge too low,” 60 feet lower than the current structure. They prefer a crossing with unlimited clearance for marine traffic. The Federal Highway Administration may also balk if the IBR doesn’t consider legitimate alternatives.

A MAX tunnel

Another component of the WMIS is a MAX tunnel under the Willamette River. This idea was floated several years ago as a solution tor the two bottlenecks in TriMet’s light rail system. Those are the Steel Bridge, which requires trains to slow down to 10-15 mph, and the short length of a downtown city block, allowing only two cars on a MAX train.

At the time the proposal was floated, the price tag was $2 billion. A staff member said it was much higher. TriMet promised to save 13 minutes of travel time by eliminating a dozen light rail stops in downtown Portland.

Metro’s 2019 report stated: “A tunnel would provide the region another option for crossing the river — generally tunnels have proven to be more resilient to earthquakes than bridges and surface systems.”

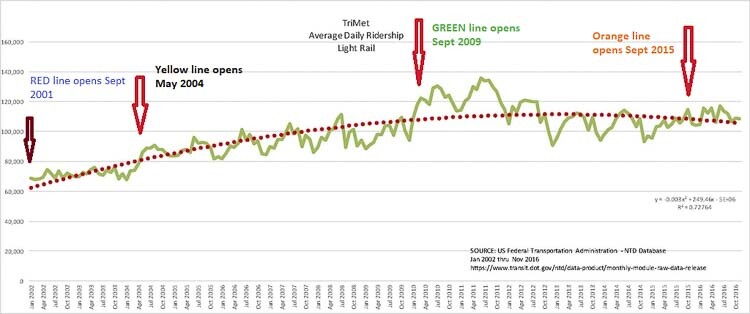

Current MAX trains cross the Steel Bridge every 90 seconds during rush hour, 40 trains per hour. TriMet can’t expand current service and meet its 2040 expected demand of 64 trains every hour, using the Steel Bridge. Yet MAX ridership peaked in the summer of 2011 and has declined ever since.

The decline in MAX ridership has occurred in spite of TriMet starting the Green Line in September 2009 and the Orange Line in September 2015. Today, ridership numbers are below the September 2009 level according to a Federal Transit Administration graphic, demonstrating that the addition of two new light rail lines added no new passengers.

The tunnel under the Willamette River has five dollar signs in the WMIS plan, indicating the cost is above $1 billion. Nobody reports how much above the $1 billion price tag the actual cost will be today, but the 2019 estimate was $3 billion to $4.5 billion.

The proposed MAX tunnel route follows the current street level light rail route. It is highly likely this will allow the later addition of subway stops downtown to actually serve people. But that will eliminate the alleged 13 minutes of time savings, long after that promise has been forgotten. The alleged “benefits” of a tunnel include increasing MAX ridership by “over 400 trips daily.”

Three years ago, Portland metro area voters rejected Measure 26-218, a $5 billion transportation package. The largest component of that was a $2.9 billion light rail line to the Tualatin-Tigard area. Former Oregon Transportation Commissioner (OTC) Robert Van Brocklin said only 4 percent of people in Portland use transit.

What might be the cost of all the projects contained in the WMIS? That is unknown. Totalling up all the dollar signs provide an extremely rough hint. The low end of all seven pages of projects adds up to 83 dollar signs. The high end is 100 dollar signs.

Their table shows the following:

- $ = less than $5 million

- $$ = $5 million to $50 million

- $$$ = $50 million to $250 million

- $$$$ = $250 million to $1 billion

- $$$$$ = Over a billion

There are five “major infrastructure improvements” listed, all but the first are in the $$$$$ category. They are:

- Reconfigure I-405/US26 (Market Street)

- Northern Connector

- North Willamette River Bridge

- Widen US26 from 217 through Vista Ridge Tunnel

- MAX Tunnel Downtown

All but the last one, the MAX tunnel, will reduce traffic congestion by adding vehicle capacity to the region. Citizens would not be wrong if they believed the MAX tunnel under the Willamette River has no legitimate role in improving mobility for Washington County and easing the log jam at the 3-lane Vista Ridge Tunnel.

And yet the official ODOT plans show adding new vehicle capacity is the bottom of their priority list.

The priorities in the Oregon Highway Plan Policy 1G are, in order from highest to lowest: A. Protect the existing system. B. Improve efficiency and capacity of existing highway facilities. C. Add capacity to the existing system. D. Add new facilities to the system.

Tolls to pay

How do ODOT and Metro propose these projects be paid for? Tolling.on US 26 and OR 217. A “fixed fee” on US 26 from Cornelius Pass Road to I-405 and OR 217 from US 26 to I-5. Additionally, they want a supplemental “high demand area fee” which would vary by time of day and include locations on US 26 and OR 217.This is part of their Regional Mobility Pricing Project.

The upfront cost for tolling is estimated from the I-205 tolling project in the regional transportation plan. The $27M includes planning & NEPA process only.

Yet, Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek recently paused the collection of tolls on I-205 for the Abernethy Bridge project until January 2026. This is due to significant community outrage by Clackamas County residents who would be forced to pay the tolls. Congresswoman Lori Chavez-DeRemer has introduced legislation in Congress to prohibit tolling on Oregon highways.

Significant traffic diversion onto side roads is projected. Some estimates indicate traffic will double in areas of Gladstone, West Linn, Canby, and even Lake Oswego. ODOT’s 2018 Value Pricing efforts predicted 130,000 vehicles diverting onto side roads to avoid tolls, once they were implemented on all area freeways.

Currently, Oregon citizens are collecting signatures to put IP-4.on the November 2024 ballot. This measure would guarantee a Vote Before Tolls could be placed on any Oregon highway. IP-4 is retroactive so the proposed I-205 & I-5 tolls will require a vote. “IP-4 is a Constitutional amendment, so our legislators and governor can’t make unilateral revisions to the will of the people,” states the website..

Oregon currently has approximately a $3 billion funding hole just to complete the I-5 Rose Quarter project, the I-205 Abernethy Bridge and 7-mile lane extension, the I-5 Wilsonville Boone Bridge project and others. Additionally, Governor Kotek prefers the Oregon legislature find a different source of funding to complete the $750 million Oregon owes the IBR. She does not want to spend General Fund revenues.

It would be premature to assume any of these projects in the WMIS will be built. But they should be front and center for discussions by Washington and Oregon legislators, by RTC and Metro Boards of Directors, and citizens in the region. The people want traffic congestion relief and to save time in their travels.

Also read:

- Belkot speaks before C-TRAN board; directors pause vote on light rail funding language until JulyMichelle Belkot spoke at Tuesday’s C-TRAN board meeting, calling her removal from the board unlawful; directors postponed a vote on light rail funding language until July amid legal challenges.

- Travel Advisory: Expect delays on northbound I-5 near RidgefieldWSDOT is warning travelers to expect delays near Exit 14 on northbound I-5 in Ridgefield as crews begin barrier and lane improvement work supporting future development.

- Large crowd expected at C-TRAN Board of Directors Meeting Tuesday, April 15A large turnout is expected at the April 15 C-TRAN board meeting, where public input and a key vote on light rail funding will follow the recent removal of Michelle Belkot.

- Letter: ‘The IBR needs a more cost-effective design’Bob Ortblad argues the I-5 Bridge replacement project is overbudget and inefficient, urging a more cost-effective tunnel alternative to avoid excessive tolls and taxpayer burden.

- Clark County beginning installation of upgraded traffic signals in mid-AprilClark County will begin upgrading multiple traffic and pedestrian signals in mid-April to improve safety, accessibility, and transportation technology.

IP-4 is an Oregon initiative and can only be signed by Oregon voters. It covers tolling on the I-5 Bridge replacement, I-205 Sam Jackson bridge tolls, and a 3rd Columbia River bridge too. Our SW Washington friends can help us by making your Oregon co-workers and friends aware of I-P4. Learn more about IP-4 and download the petition at https://VoteBeforeTolls.org

Dean — thank you for your hard work and dedication in supporting IP-4. It IS the main way people can GUARANTEE their voice is listened to by our government!

TOLLING is a hugely inefficient means of raising money for transportation, as you well know. In Seattle on the I-405 system, fully 68% of funds raised by tolls in 2021 went to the “cost of collection”. What a sad was to waste the people’s money.

Southwest Washington citizens need to be sharing the Vote Before Tolls website with all their Oregon friends!

Merry Christmas. Gathering far more than the needed 200,000 signatures for IP-4 will guarantee 2024 is indeed, a Happy New Year! 🙂

I would love to have a way to get from Vancouver to Washington County OR without having to go through the Portland cesspool. Heck, I would be willing to pay tolls for that!