Teachers want big raises from new state money, but districts argue they’re losing millions in local funding

CLARK COUNTY — There’s an old saying that may apply to what’s shaping up at school districts across Clark County, and around the state, this Summer: Mo’ money, mo’ problems.

When the Washington Legislature approved a supplemental budget last March that included more than $2.1 billion over two years for teacher compensation, it was seen as a major victory for K-12 educators across the state. The state Supreme Court ruled earlier this month that the legislature had finally fulfilled its constitutional duty under the McCleary Decision to fully fund education.

But now it appears there is a battle brewing at school districts across the state between administrators and teachers over just how much of that money they can expect to see.

In Battle Ground, teachers say the district received enough from the state for them to see a 23 percent increase. The district is offering less than two percent according to union officials. In Washougal, where teachers earn, on average, $8,000 less per year than at other districts, they were hoping for a 21-percent raise. Frank Zahn, who just recently stepped down as president of the Washougal Association of Educators (WAE), says the district is offering far, far less than that.

“The salary schedule that the Washougal school district offered us,” he says, “the first one they offered us in the second negotiation, our teachers would have to take a pay cut at the beginning of the year.”

To understand what’s happening requires digging into what the legislature did in order to satisfy the high court’s mandate.

The McLeary mandate

Back in 2012, the Washington State Supreme Court determined that lawmakers had failed their constitutional duty to fully fund basic education in the state. The case actually began in 2007 when several school districts and teachers’ unions sued the state over inadequate school funding. Stephanie McCleary, personnel director for the Chimacum School District, became the reluctant face of that lawsuit. Her children, who were in grade school, are now either finished with college, or halfway through.

In the 11 years since that case began, state lawmakers spent session after frustrating session trying to figure out how to fulfill their constitutional obligations. In 2014, the state Supreme Court issued a first-ever contempt order against the state legislature, and the next year levied a $100,000-per day fine against the state. The legislature ultimately had to set aside $105 million to settle those fines.

As part of the agreement to set aside $1 billion for teacher pay raises next year, the state put a temporary cap on the amount school districts can receive from an operations levy. Starting next year, those will be replaced by Enrichment Levies, which are capped at $1.50 per $1,000 of assessed value, then climbing with the rate of inflation in 2020 (Read more from the Department of Revenue here). While those caps will eventually be raised, school districts are still trying to determine where things will shake out.

Time, resources, and incentive

One of the primary questions seems to center around TRI pay. Otherwise known as Time, Resources, and Incentive pay, it is additional compensation most teachers receive, and which is paid out of local school district budgets. The money was originally intended as a way of compensating teachers for additional work beyond their usual class load. But in many districts, it is now simply an expected part of the compensation package.

In Evergreen School District, for instance, the average teacher will earn over $58,000 next school year. That’s a base salary increase of 1.9 percent, according to the district. However, when increases to TRI pay, and other compensation such as stipends many districts give for classroom materials, the total pay increase is around 6.4 percent, to an average of more than $76,000.

The Evergreen School District says they actually don’t stand to see much of the legislature’s $1 billion for teachers, because the reduction in levy funds, high TRI pay, and a high experience level among existing staff, offset nearly all of the state funding increase.

The Evergreen Education Association (EEA) argues that the state’s funding should lead to an increase in teacher base pay of roughly 15 percent, and a 27 percent increase for classified staff. At a recent meeting the union agreed to hold a strike vote on August 23 if a resolution can’t be reached. The District says teachers are under contract through next school year, and their position is to honor that contract.

In Battle Ground, teachers are demanding a 23 percent increase, while the district is offering “far less” according to Battle Ground Education Association (BGEA) president Linda Peterson.

“The amount of dollars sent down, and there’s an average of around $69,000 for each funded, certificated teacher. We want those dollars to go into teacher salaries,” says Peterson.

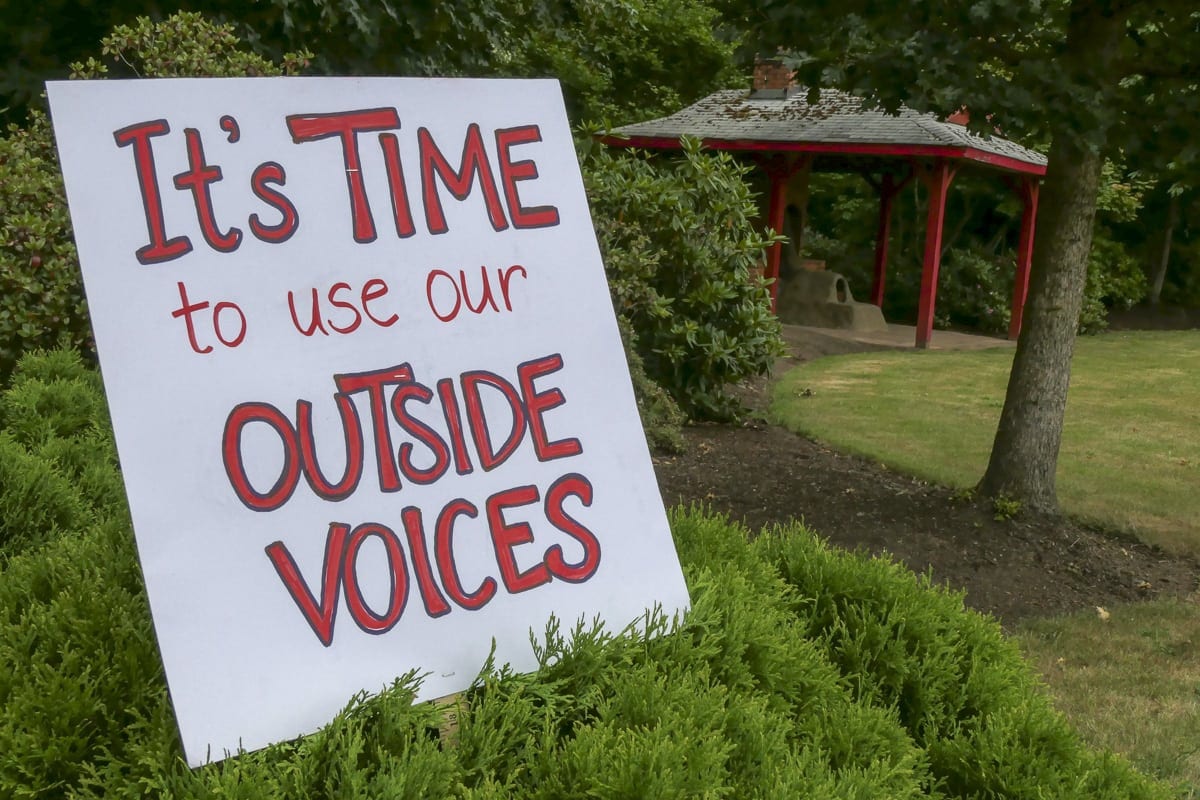

Around 300 teachers, parents, and students recently showed up outside of Battle Ground district headquarters, holding signs and chanting things like “23 percent is well spent,” and “teachers united will never be defeated.”

In an e-mailed statement, Battle Ground superintendent Mark Ross brought up similar concerns to what we heard from Evergreen School District.

“As the state takes on its responsibility to cover the costs of basic education, we mean to comply with the legislature’s intent,” Ross wrote. “But in Battle Ground, we must also consider that due to the McCleary decision our local levy will be substantially reduced in the next two years, and that we have relied heavily on that levy to support unfunded staff and provide additional pay to teachers in the form of time, responsibility and incentive (TRI) for work outside classroom hours. The district has a responsibility to spend taxpayer dollars wisely with a long-term view toward sustainability and students’ success.”

According to Peterson, Battle Ground will see its levy funding cut by around 44 percent next school year. “That’s a big cut, but that’s the state doing that,” she says. “And the district, and many districts are saying with that levy cut, those dollars cut, we can’t fund education. We can’t fund all of our programs, we can’t fund all of the things that it takes to run a school system.”

Peterson says BGEA hasn’t yet determined if it will set a possible strike vote date, but that those conversations are ongoing.

Frank Zahn, a teacher in Washougal school district who recently completed his term as president of the Washougal Education Association (WEA), says their problem is somewhat different.

“Unlike the Battle Ground school district, the Washougal school district’s ending fund balance has been enormous, percentage-wise,” Zahn says. “They currently report, I believe it’s 16 percent ending fund balance.”

Teachers in Washougal are seeking a 21 percent bump in pay. In part because of the money the state is sending down, and in part because educators there earn, on average, around $8,000 less than teachers with similar experience in neighboring districts. “When I speak to a young teacher, and they say ‘why would I stay here?’ I have to answer honestly, ‘why would you?'” Zahn says.

WEA recently held a vote of no confidence in outgoing Superintendent Mike Stromme, with all but one member supporting the move.

“The decision to go forward with the vote of no confidence was promulgated by a simple lack of response from the district we got at the first negotiations, and continuing on,” says Zahn. “And then just a review of his three-year career here.”

Zahn admits the vote was also somewhat of a message to incoming Washougal schools Superintendent Mary Templeton. The former Spokane schools Human Resources director will take over in July.

Are teachers underpaid?

“We have a teacher shortage,” Peterson says, “because when you graduate from college and you start out making $35,000, when in other fields you’re making much more, we’re losing teachers. The stress of the job has increased immensely, the responsibilities have increased, so we’re not getting teachers.”

National surveys have shown consistently that the majority of Americans believe teachers should earn more. However, a poll done last year by EducationNext.org found that Americans also had very little understanding of what teachers actually make. As of 2016, the average teacher nationally earned over $58,000. That was $18,000 more than survey respondents believed teachers made. Once respondents were told what teachers in their state actually earned, the majority thought it was just fine.

But others say the raw numbers don’t tell the full story. According to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), a full-time teacher in Washington state earned, on average, just over $60,000 last year. That’s over $2,000 more than the median statewide income, even before accounting for TRI pay. But teacher unions say that, compared to workers with a similar level of college education, teachers are actually underpaid. When measured in “constant dollars” — based on the consumer price index — teacher salaries have actually been decreasing since 2009.

The National Center for Education Statistics also points out that, in Washington state, the average annual earnings for workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher in the U.S. is well over $79,000 a year. That would make the teacher pay gap in Washington state nearly 30 percent. In Constant Dollars, their report says teacher pay has fallen around 8 percent between 1999 and 2017.

“You’re not going to get people into education unless you pay them a professional wage,” Peterson says.

“The problem that we have now is that we can’t attract the best and the brightest to come teach school,” Zahn adds. “I mean, you get out of high school and you can go join the army, and you’ll be making more than a beginning teacher in two years.”

Little state guidance

As part of its funding legislation, the state eliminated its salary schedule, opting instead for a base minimum wage for starting teachers of $40,700, plus regionalization. That means a district like Battle Ground would end up with a starting salary of just over $43,000. Where things go from there, however, will be part of the contract debates going on across the state.

While OSPI has provided some measure of guidance to districts, it is not weighing in on the issue of whether TRI pay should count when it comes to whether a district is in compliance with the starting wage requirement, or what the salary scale should look like for more experienced teachers.

Nathan Olson with OSPI says the vague input from their office is standard practice, given the wide latitude local districts have in how they want to allocate money from the state. One school might want more counselors, he says, while another emphasizes librarians.

“How much [the districts] pay teachers is a negotiation between the district and the local bargaining unit (the local union) – OSPI has nothing to do with those negotiations,” Olson wrote in an email. “Again, a certain amount of money is allocated to districts from the state, but as you saw with McCleary, too often the allocated money wasn’t enough to pay what a teacher actually costs. McCleary helped increase the allocation, but it is still up to districts (and of course market value) to determine the exact pay for each teacher.”

Districts worry the loss of millions in local funding will force them to cut into what are known as “unfunded” positions — essentially classified staff not paid for by state revenue.

“All of the other concerns are, I guess, understood,” Peterson says, “But the state also sent more money in other areas. So although the levy is decreasing, other moneys are increasing.”

Zahn says their calculation is that Washougal will lose around $800,000 when the levy cap goes into effect. That’s understood, but teachers believe the legislature was unequivocal in what money approved during this most recent session was intended to do.

“The total amount of money we think the Washougal School District is receiving from the legislature is $5.2 million additionally, beyond what they had already received,” Zahn says, “And according to our notes $3.2 million of that is for teacher salaries. Not administrative, not classified. Teacher salaries.”

“Educators were sent specific dollars for salary. That’s what we’re saying,” says Peterson. “So we do not believe that our district, or any district, should take those dollars and somehow spread them out to offset whatever they believe is going to be a deficit. Because the dollars were sent for educators salaries. That’s really the bottom line.”

While some districts appear to be gearing up to play hardball, others have gone along with the demands. Teachers in Mossyrock, for instance, recently got an average 25-percent raise approved. WEA believes teachers should see at least a 15-percent increase from the new state money, while staff such as bus drivers and teaching assistants should see a 37-percent bump in pay.