Carolyn Schultz-Rathbun

For ClarkCountyToday.com

FERN PRAIRIE — Fern Prairie Cemetery Commissioner William Zalpys can make arrests. Although Zalpys says he has never used it, state law gives him the “authority of a police officer” within the cemetery as well as “within such radius as may be necessary to protect the cemetery property.”

That’s because Zalpys, who works for the city of Vancouver at Park Hill Cemetery, also works part-time as both a commissioner and the sexton of Fern Prairie Cemetery.

“It’s old terminology,” says Zalpys. “The sexton plots the areas, makes all decisions on grounds and burials. And I can arrest somebody.”

It’s just one fascinating thing about a very fascinating position.

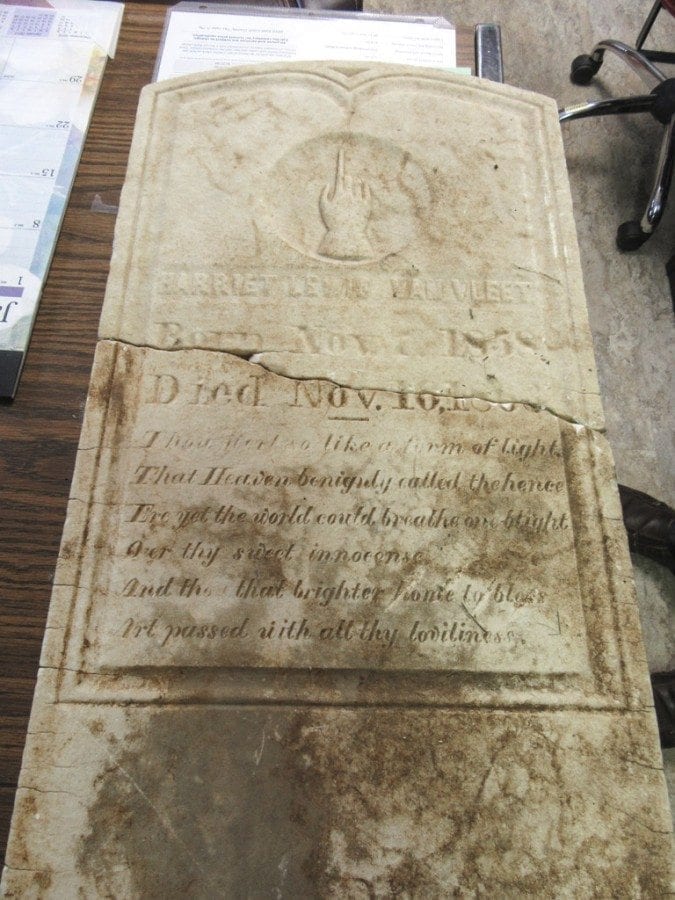

The markers at the old pioneer cemetery, established in 1855, read like a Who’s Who of early Clark County life. A Livingston, for whom Camas’ Livingston Mountain is named. Two territorial legislators. And the first female doctor in the Washington Territory — probably.

“That’s what Pat Jollota says,” says Zalpys. “I haven’t been able to prove that — but in Clark County, definitely. Louisa Van Vleet Spencer Wright. She served Native Americans, and everyone else nobody wanted to. She was tying up a team of horses on Ribbon Day, Memorial Day, when a horse kicked her in the jaw.”

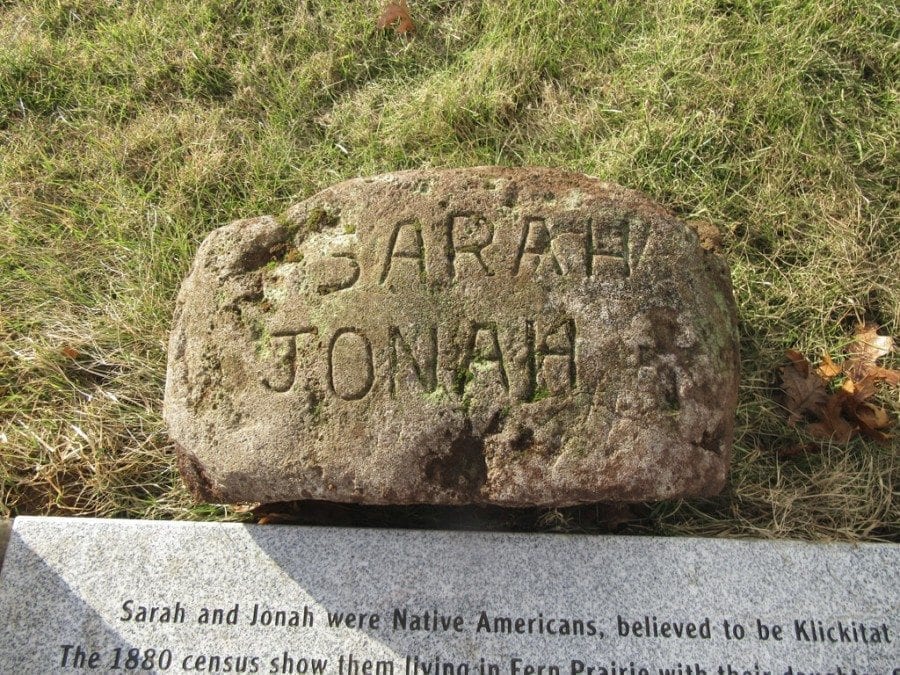

Two native Americans are buried near Wright under a single rock that reads Sarah Jonah, with a small cross in the corner. At first, Zalpys says, he thought it was a single person, Sarah Jonah, who is recorded as being the first native American convert to Christianity at the nearby Fern Prairie Methodist Church.

But the records showed two native American graves there. Zalpys did some research and discovered a woman, Sarah, listed in old census records as a berry picker, and her husband, Jonah, a hunter. With a lot more digging, he was able to identify them fairly confidently as members of the Klickitat tribe.

There are also three Confederates buried in the cemetery, including a husband and wife.

“I have a big picture of the woman sitting with a big pipe in her mouth,” says Zalpys. “With her husband behind her. They lived up here somewhere.”

Zalpys says it has been a struggle to get volunteers to decorate their graves properly on Memorial Day.

“I told them, ‘Don’t put a Union flag on a Confederate grave. The protocol is a Confederate gets a Confederate flag.’ And I come back, and there are crossed flags, Union and Confederate. The next year, the same thing. But you don’t put a Union flag on a Confederate grave. The rules are put down by Congress.”

Fern Prairie isn’t just about history, though. There were 31 burials there last year. The cemetery has recently added an infant section, with lower-priced graves, and does green burials, meant to allow the body to decompose naturally. Zalpys says people have been buried in baskets, sheets, and cardboard caskets.

“Two people out here,” he says, “are in their favorite quilt.”

And in September the cemetery had its first Muslim burial, with the body tilted to face Mecca.

As he walks through the cemetery with a visitor on a recent afternoon, Zalpys mentions grave after grave: how he died, how long ago she was buried, how often his widow visits. Two of the graves he points out have “Zalpis” on the headstone. His parents are buried in the cemetery.

The hardest thing about the job, he says, are the children.

“There was a young man, at Park Hill. We were putting his ashes in the columbarium. His widow, and a child. Three years old. And he said, ‘Mommy, where’s Daddy?’ You never get over the children.”

When Zalpys became a cemetery district commissioner in 2002, he and the other new commissioners found the records in disarray. Some graves had been sold three times. One section had been mismeasured, with gravesites too close together.

“We needed to plot everything here. I put tent stakes in the ground, ran lines. I had to poke every single burial out there.”

He also built an office and a columbarium, instituted regular office hours, paved the road, ran water in, installed a porta-potty, and updated the record-keeping technology.

“It’s not rocket science,” he says. “You have to be willing to make life easier. We’re not getting donations for no reason. You have to use the public money wisely.”

But the heart of the job is still people.

“It’s assisting families with grieving,” Zalpys says. “The more comfortable you feel, the more comfortable the family feels — the more you’re open and explain every step.” He stops at a grave.

“This boy burned up in a fire. I came out at night and the family was there, trying to put a six-foot cross into the grave. I said, ‘Guys, I know what you’re trying to do. I understand. But you just can’t do that.’”

Zalpys tries, though, to be as flexible as he can.

“I come from the city cemetery (Park Hill), and there are lots of rules,’’ Zalpys said. “You can’t do this, can’t do that. I’ve tried not to make too many rules. As long as I can mow around it.”

Un abrazo..Feliz Navidad

Javier.

Reading the gravestones in a pioneer cemetery is both inspiring, and sobering.