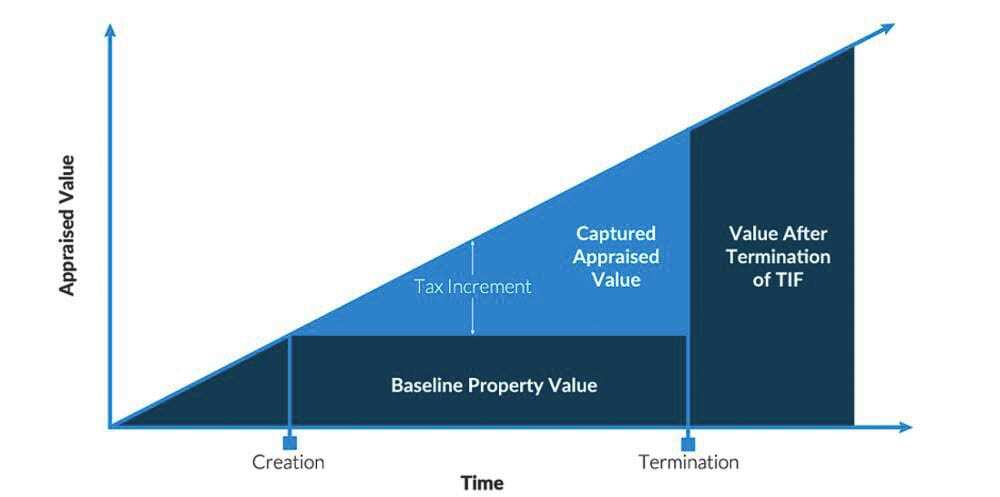

TIFs allow borrowing money for development based on future property tax values

Members of the state legislature have advanced HB 1189 and SB 5211. The proposal would create a new way for local governments to borrow money, paid for by expected increases in future property tax revenues.

The bill “authorizes local governments to designate tax increment financing areas and to use increased local property tax collections to fund public improvements.” The municipality must designate a specific geographical area, specify the public improvements, and the TIF can last no more than 25 years.

Proponents say TIF is a tool that allows municipalities to promote economic development by earmarking property tax revenue from increases in assessed values within a designated TIF district. Rep. Ed Orcutt, (Republican, 20th District) said this specific bill would allow local governments to bypass the 1 percent restriction on property tax growth limited by I -747.

In the state senate, the bill passed with bipartisan support, 45-2 with Senators Lynda Wilson (Republican, 17th District) and Ann Rivers (Republican, 18th District) supporting the Democrat majority. In the House, the vote was 64-33 with Reps. Brandon Vick (Republican, 18th District) and Larry Hoff (Republican, 18th District) voting in favor, as Reps. Paul Harris (Republican, 17th District), Vicki Kraft (Republican, 17th District) and Orcutt voted against.

Matt Ransom, director of the Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council (RTC) mentioned the legislation in his briefing to the RTC Board last week. He called the TIF legislation “most profound.” It becomes another tool for seed money for transportation and infrastructure projects. “I think it’s significant,” he added. He later shared he had not reviewed HB 1189 for exact policy implementation, mechanics, or limitations.

History of TIFs

The rules for tax increment financing, and even its name, vary across the 48 states in which the practice is authorized, according to a 2018 report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in Cambridge, MA. The designation usually requires a finding that an area is “blighted” or “underdeveloped” and that development would not take place “but for” the public expenditure or subsidy.

It is only a bit of an overstatement to characterize the “blight” and “but for” findings as merely pro forma exercises, since specialized consultants can produce the needed evidence in almost all cases. In most states, the requirement for these findings does little to restrict the location of TIF districts.

TIF expenditures are often debt financed in anticipation of future tax revenues. The practice dates to California in 1952, where it started as an innovative way of raising local matching funds for federal grants. TIF became increasingly popular in the 1980s and 1990s, when there were declines in subsidies for local economic development from federal grants, state grants, and federal tax.

The report’s conclusion stated “although results are mixed, TIF often fails to meet its primary goal to increase real estate development and other economic growth. Based on these findings, the report offers recommendations to make TIF districts more successful, equitable, and efficient.”

The pro and con

An analysis by the DBS group in Wisconsin reported “while it’s often an attractive option for developers and communities, it has its downsides too.” The upsides include seed capital to renovate blighted areas and grow the tax base. It also includes the potential for job growth and increased sales tax revenue. The downsides are that not all projects thrive, and there can be battles between government agencies fighting to retain those tax revenues. Battles between school districts, cities, counties and fire districts are cited.

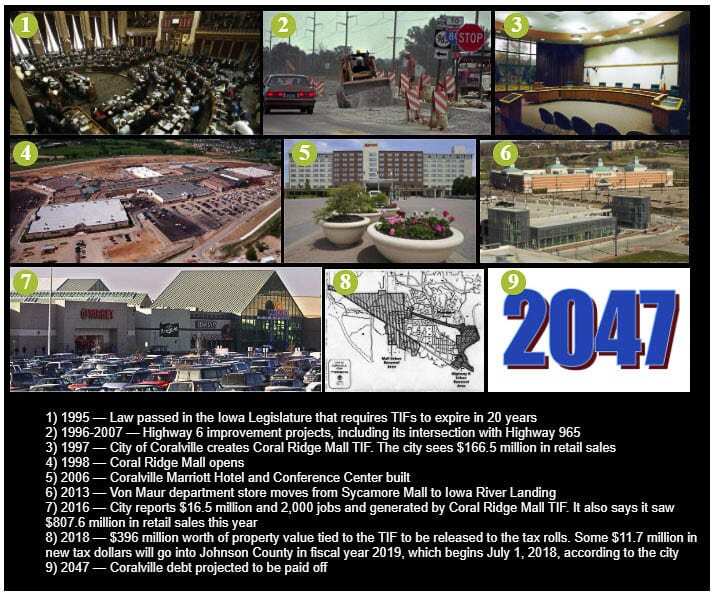

A recent article in the Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette highlighted the challenges asking, Has TIF been successful for economic development in Iowa?

Flash back 20 years and little existed to just east of the Interstates 380 and 80 intersection in Coralville, but even then it was one of the busiest junctions in the state.

Today, millions of people a year travel to the retail hub anchored by the 120-acre Coral Ridge Mall site, which opened in 1998. Half a dozen shopping centers have sprouted around the mall and nine hotels are within a stone’s throw. Updated roads, bike trails and hundreds of homes add to a vibrant, busy area.

Yet there was a downside. TIF use by Coralville expanded to become one of the highest rates in Iowa. They report 45 percent, or $700 million, of Coralville’s $1.6 billion in property value was sequestered in TIF districts in fiscal 2016. The city is so leveraged it damaged its credit rating.

Businesses moved from one location to the Coralville TIF, depriving other municipalities of needed tax revenue. One deal prompted the Iowa legislature to create an ‘anti-piracy’ provision to prevent one city from using TIF to entice a company from leaving another city without the permission of the other city.

“A baseline property value is set when the district is created, and the jurisdiction sets aside future taxes generated above the baseline to pay off debt from the investment, starving other taxing authorities of their share,” reports the Gazette.

“In many cases, TIF is used really as nothing more than a cash cow to finance city spending that could and should be financed in other ways,” said Peter Fisher, research director, Iowa Policy Project.

The article includes a graphic showing Coralville TIF debt won’t be paid off until 2047. The Iowa law has changed many times, as politicians sought modifications to allow flexibility away from the original purpose of renovating areas.

One news story reports: “With tax revenues frozen for 20-30 years, the real value of that money steadily decreases over time, by an average about 2 percent per year. (Some TIF policies do account for inflation.) To balance out this decrease in the real value of taxes being collected, jurisdictions might have to raise taxes, find revenue in other forms, or cut back on services.”

The Lincoln Institute reports “there may be an incentive for municipalities to “capture” revenue from growth that would have occurred in the absence of TIF (to collect taxes that would have gone to school districts).”

Policy makers should use TIF with caution, advises the institute. “It is, after all, merely a way of financing economic development and does not change the opportunities for development or the skills of those doing the development planning. Moreover, policy makers should pay careful attention to land use when TIF is being considered. Our evidence shows that commercial TIF districts reduce commercial property value growth in the non-TIF part of the same municipality.”

Bloomberg reports TIFs are funding numerous convention centers, with revenues commonly sought by hotel developers seeking to build nearby. In other cases, TIF revenues have been used to fund public transit, affordable housing, and other, more self-evidently public-serving projects.

Transit TIF has been used to fund projects in Chicago, San Francisco, and Denver as part of a broader menu of “value capture” strategies that help cities fund large-scale infrastructure improvements, according to the news report.

Portland currently dedicates about 40 percent of its TIF revenues to affordable housing, according to the news report. Over nine years, the program generated nearly a quarter of a billion dollars for affordable housing, according to City Observatory. In the city’s largest TIF district, which includes the fast-gentrifying Pearl District, TIF has generated $83 million and helped produce 2,200 units of affordable housing in combination with other funding sources.

In the Washington legislature, Rep. Orcutt fought to put this issue to a vote of the people. He introduced an amendment saying:

Media Player Error

“The ordinance must be submitted to the voters at a special or general election and must be approved by a majority of the persons voting. The ballot title shall include the language substantially similar to the following: “shall the local government be authorized to suspend the one percent limit on property tax increases and form a tax increment financing area”.

The Orcutt amendment was rejected in the House Finance Committee. He emphasized that citizens want to keep the current 1 percent tax limit on the growth of property taxes.

All local legislators were contacted by Clark County Today asking why they voted in favor of or against the TIF bill. Senators Rivers, Wilson, Annette Cleveland (Democrat, 49th District), and Representatives Vick, Hoff, Sharon Wylie (Democrat, 49th District) and Monica Stonier (Democrat, 49th District) did not respond.

“It’s pretty complex how it does it,” said Orcutt. “But simply put, it allows local governments to do an end run around the 1% limit on property tax growth and allows them to collect more than current law allows – and what was allowed under the provisions of I-747. I stood up for the voters when they demanded a 1% growth limit.”

Harris simply concurred with the Orcutt response.

“I have been and am opposed to increasing the 1% property tax limit,” said Kraft. “Especially at a time like this when so many people have been hit hard financially over the past year. I’ve heard from many, many constituents this session who have spoken loud and clear – NO new taxes! I will not vote to raise their taxes.”