Morning commute times could double after $5 billion expenditure

The resurrection of the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) is now complete. Administrator Greg Johnson and his Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) team is proposing an extension of TriMet’s MAX light rail into Clark County as part of a new bridge over the Columbia River. The details were revealed during meetings of the Executive Steering Group (ESG) and the 16-member Bi-state Bridge Committee of legislators Thursday.

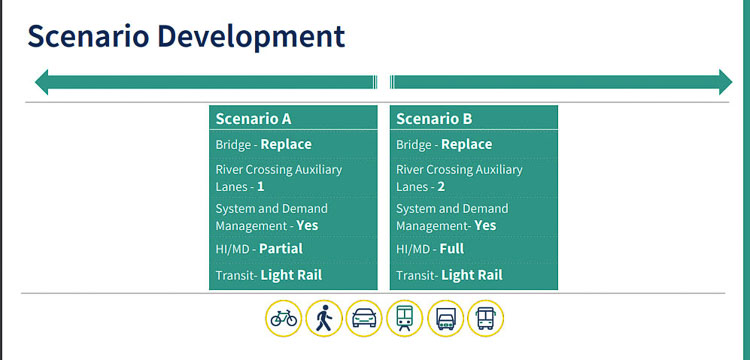

Citizens on both sides of the river have expressed their desire for traffic congestion to be reduced to save time in their travels. The bridge replacement proposal will only provide three through lanes for vehicle traffic, exactly what is present today. Yet to be decided is whether there will be one or two auxiliary lanes added for merging and weaving at interchanges, and interchanges at Hayden Island.

For the morning rush hour, the IBR team projects travel from I-205 on the north end of Vancouver to I-405 would go from 29 minutes today, to either 60 minutes with one auxiliary lane or 57 minutes with two auxiliary lanes.

An Oregon Supreme Court Justice had previously labeled the CRC nothing more than “a light rail project in search of a bridge.” The failure of the $3.6 billion CRC nearly a decade ago was for many reasons. Those included light rail, tolling, a bridge too low, and providing only a one minute improvement in the morning, southbound commute.

What is different today? Apparently, not much.

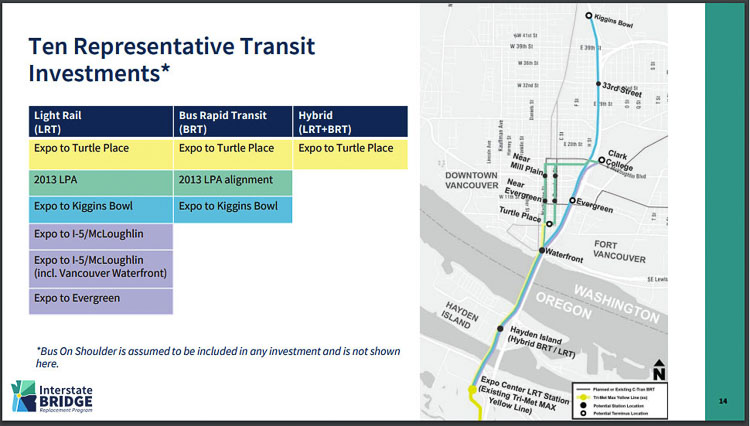

The IBR team is proposing a light rail extension along I-5 to Evergreen Blvd. They believe a light rail stop at Evergreen Blvd. near the Vancouver library is the best location to connect C-TRAN with TriMet. In the previous proposal, light rail ran through downtown Vancouver.

“Light rail represents the best investment opportunity for the project,” John Willis of the IBR staff told the ESG this morning. Shawn Donaghy, CEO of C-TRAN said this project presents the best opportunity to connect C-TRAN with TriMet. He believes the “running I-5” scenario is best, rather than going on downtown Vancouver streets.

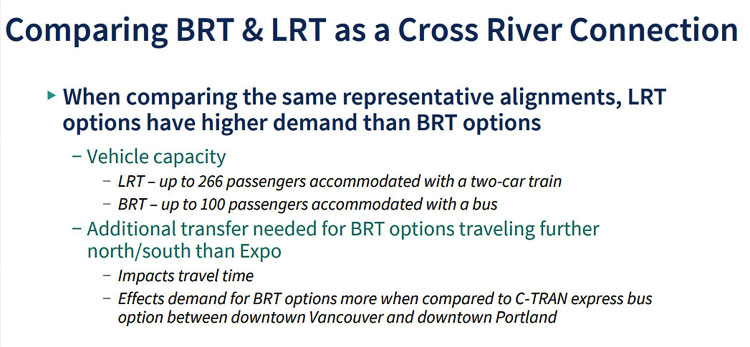

The proposal cites a 14-year old analysis from 2008 indicating light rail had 19 to 25 percent more riders than bus rapid transit. Proponents say the difference has increased today, which flies in the face of the facts. In July 2008, TriMet’s MAX ridership was 784,700 for the month. Eleven years later, ridership was 755,330, or nearly 30,000 fewer boarding riders.

There was no BRT service offered in 2008. Today, C-TRAN is operating The Vine and has broken ground on its second line along Mill Plain. TriMet is working to provide its first BRT line along Division street.

The IBR team has previously said building light rail would stimulate demand. Yet TriMet built two new lines, the Green Line in 2009 and the Orange Line in 2015. Ridership peaked at 820,400 in 2016, and has then dropped by 8 percent to 755,330 just three years later. In the pandemic ridership dropped 56 percent to 332,000 in July of 2021.

TriMet only offers MAX light rail service at 15 minute intervals. A recent analysis indicated the most people the MAX Yellow Line could serve during the three-hour morning commute would be 4,000 people. They would be traveling an average of 14 mph.

The “modeling” cited by the IBR team indicates transit ridership will increase from 4 percent to 11 percent by 2045. Yet their own data shows transit ridership only carries 1.7 percent of people today. There is no evidence cited to verify the 11 percent transit ridership number in their projection.

The presentation flies in the face of the 2018 PEMCO travel survey. It showed that 94 percent of people prefer to use their private cars for travel. That was before the pandemic lockdowns triggered a significant decline in transit ridership locally and nationally.

The IBR comparison was only along similar alignments for BRT and light rail. They ignore the potential that BRT can depart from different locations and travel many different pathways to serve transit riders.

Cost estimates for transit were also shared by the team. They appear to have updated CRC data estimates from 2012, offering a “high” and “low” estimate for both light rail and BRT costs. Light rail cost estimates run from $770 million to $1.3 billion. Bus rapid transit cost estimates run from $640 million to $1.01 billion.

Estimates are also provided for how much federal money the project team believes could be received from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). Both projects indicate the states would need to fund anywhere from $280 million for BRT to a high of $470 million for light rail.

The proposal would extend the Yellow Line MAX line from the Expo Center station to Hayden Island, and then along the west side of Interstate 5 up to Evergreen Blvd. This option would remove an unspecified amount of WSDOT-owned land along the corridor. That would limit the ability to add additional lanes for vehicle travel in the future.

The IBR team indicates its comparison of BRT with light rail would require all BRT passengers to get off the BRT buses and transfer to MAX at the Expo Center. This added time, making BRT less desirable for passengers.

Why would one end all BRT lines at Expo in north Portland? People want to go to the Lloyd Center or downtown Portland area to transfer to other transit or get off at their destination in these locations. A required transfer at an undesired location to a slower mode of travel appears counter intuitive.

Saving travel time and reducing traffic congestion is people’s top priority. The IBR surveys indicate 78 percent of Washington residents have that goal and 70 percent of metro area residents overall share this goal.

The proposal estimates the morning southbound commute times will get worse, doubling travel times from either 99th Street or I-205 going into Portland.

In the evening, the proposal indicates travel times will be reduced by 23 to 25 minutes if two auxiliary lanes are added. If the decision is made to add only one auxiliary lane, the travel time improvement is reduced to just 11 minutes. The IBR staff estimates no change in travel time between I-405 in Portland to I-205 in north Vancouver in the “no build” scenario comparison.

The study clearly shows the addition of new lanes (auxiliary) does save time in the northbound direction. Why wouldn’t they propose to add new through lanes to the entire 5-mile “bridge influence area” to save further travel time? Why does the addition of auxiliary lanes not save time in the morning commute?

That question was asked by Senator Lynda Wilson (Republican, 17th District). The answer was the Rose Quarter bottleneck continues to be the problem for southbound traffic congestion that backs up into the 5-mile bridge influence area. That restriction didn’t impact their northbound traffic study which began north of the Rose Quarter. The IBR team didn’t reveal impacts for broader areas of the I-5 corridor.

Overall, the IBR team estimated the project cost would range from $3.2 billion to $4.8 billion. The ESG and the 16 legislators overseeing the project will now have roughly two months to weigh in with concerns and suggestions and possible changes.

There was no mention by IBR staff members of the fact that they have asked the Coast Guard for permission to offer a bridge providing 116 feet of clearance for marine traffic. That triggered “mitigation” payments of $86.4 million in the failed CRC. Citizen Dave Rowe brought up the issue during citizen communication.

There also was no mention of a double-stacked bridge versus a two-bridge option.

A modified Locally Preferred Alternative (LPA) will be recommended by July. There is a scheduled meeting July 21 of the 16 legislators where the IBR staff will be seeking approval to move forward with the modified LPA.

April 21, 2021 EMERGENCY TOLL RATE HIKE IN WA

Toll increase likely for State Route 520 Bridge due to decline in revenue

OLYMPIA, Wash. — Drivers could see a sharp toll rate increase for State Route 520 Bridge by this summer as the state works to mitigate reduced revenues that began with the coronavirus pandemic.

The Washington State Transportation Commission began discussing new toll rates, which could include a 120-day emergency rate, followed by a permanent rate. To meet upcoming financial and legal obligations, toll rates could increase an estimated 25-35%.

Due to revenue projections and absent subsidies, a toll rate increase will be required for the state to meet its financial and legal obligations, according to information presented to the Transportation Commission on April 20.

Toll rates could be set by June 15 and take effect by July 1. Full story at link

Toll rates on WA SR 520 Bridge fluctuate throughout the day, with the highest tolls during peak commute times on weekdays.

**520 Bridge between Seattle and the east side Toll Rates as of April 21, 2022

One Way Roundtrip

Toll for a car weekday 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. $6.30 $12.60

-$2 w/ a transponder that tracks movements $4.30 $ 8.60

30% rate increase on car transponder rate $5.60 $11.20

(50 weeks a year, 5 days a week, $11.20 per day) $ 2,800 annual tolls

Multi-axle toll rates

Vehicles with more than two axles will pay a higher pro-rated toll rate.

Peak time 11 AM-6 PM tolls for a 6-axle vehicle- $13.95 one-way, $27.90 roundtrip

Toll rates are expected to increase over time

s to jam the hate

off was to jam the hated loo

The IBR team has proposed tolls for BOTH the proposed I-5 bridge replacement, and the I-205 bridge, and has not revealed what those toll rates would be.

The Washington State Transportation Commission, all appointed by Governor Inslee, set the toll rates for WA.

This is the link for the current rates on the 520 bridge between Seattle and the eastside as an example of bridge toll rates in WA state

https://wstc.wa.gov/programs/tolling/sr-520-bridge/

This is a link for the already approved toll rate hike for the WA 520 bridge, that takes effect in 2023.

The rates were increased more for the peak traffic periods

Tailored Toll Increases Averaging +15% on 7/1/2023

.

The whole point of this rip-off was to jam the hated loot rail down our throats, according to the Oregon Supreme Court decision of Feb 16, 2012.

http://stopcrc.com/docs/crc-light-rail-oregon_supreme_court_crc_decision-1.pdf

A massive, unneeded, unwanted waste of 100s of millions of dollars… blowing a hundred-million dollar hole (to start) in the local economy to pay for ever-increasing tolls to help TriMet get bailed out of their billion+ dollar debt as loot rail trips continue to plummet… and those in cars have to pay for tolls both to get across the bridge and then again when their over it, with no congestion relief of any kind.

No other option was ever considered. it’s a huge, total theft shilled by those who either get rich off this crime or by those who won’t have to pay these tolls to go to work.

Please share your thoughts with the committee at the next IBR meeting that allows public comment.

And since Annie, the mayor of Vancouver, seems to be aboard with this, how about let’s starting a re-call effort for her and any other elected official supporting light rail. The citizens HAVE spoken several times and have consistently voted down the crime train.

Annie and others who represent Wash./Vancouver voters are now turning a blind eye to those votes. Time to remove the mayor from office; she is not listening and is costing Vancouver millions of dollars with her willful refusal to accept voters’ desires.

Well, it looks like the “Interstate Bridge Replacement” is going to become another false start. Note that (on average) every “light rail” project in the United States for the past 25 years has cost twice as much and delivered half the passengers as claimed in proposals. The 11% “share” of passengers using light rail is nothing but a wild dream of the car-hating “urban planners.” The route is limited to single (articulated) cars and 14 mph through city streets. Rail transit is inflexible (a problem when “unexpected” development occurs off the rail route) and very expensive to build and operate (but government officials love the “union jobs” (that fund politicians) and big construction contracts (that fund the inevitable graft)). Losers are the commuters and the tax payers.

The failure to add lanes to the bridge makes this whole project a pointless exercise–the bridge is near it’s practical capacity now, so a new bridge with the same number of lanes (built to meet current specifications) will only allow a minuscule increase in traffic volume. I suggest that the proposal be “tabled” until such time that Oregon is willing to actually deal with reality rather than imaginary (politically correct) conditions.

Oregon/Portland pols see Clark County residents as an untapped piggy bank for their light rail money pit

Please share your thoughts in writing at least, and consider testifying at the next IBR meeting to consider which alternative design the committee is going to push.