Oregon law prohibits tolling funds from helping C-TRAN or low income Clark County residents

Is Oregon’s tolling program simply a money grab? Is it about creating “roads for the rich”? It’s very regressive, says Vancouver councilor Erik Paulsen.

For the past two months, the Vancouver City Council has been discussing the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) and tolling. Initially, the tolling discussion was about a funding source for the bridge replacement. How to pay for an expected $4 to $5 billion project.

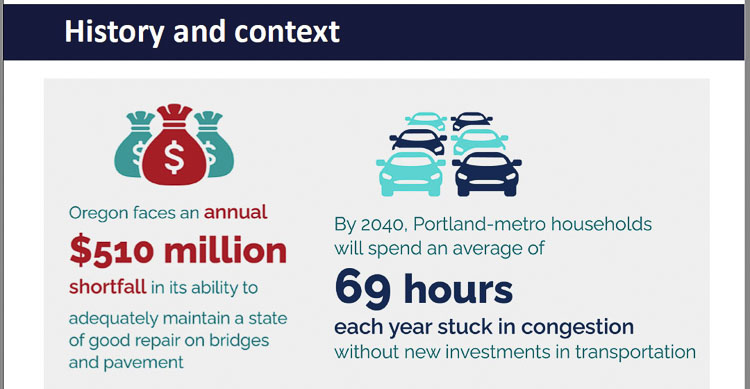

But on Monday, the council members received a briefing from the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) on their plans for tolling I-5 and I-205. Oregon has a $510 million annual funding deficit for maintaining roads and bridges. By 2040, people will spend an average of 69 hours being stuck in traffic congestion. Portland has had the eighth worst traffic congestion in the nation.

Councilor Ty Stober began the effort to question the program and motives of the ODOT tolling program.

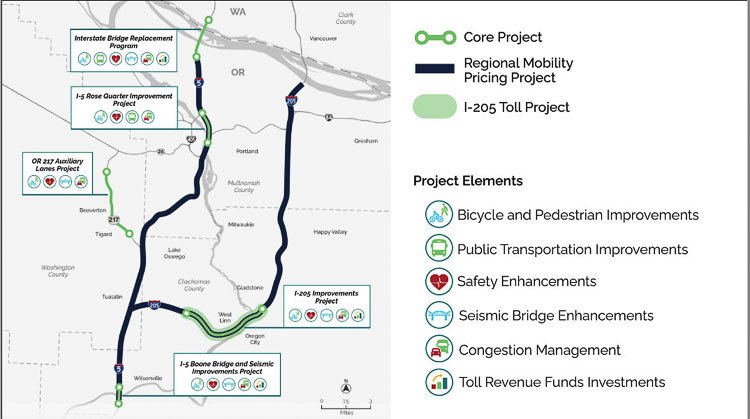

“When you look at the map, it very clearly looks like it is trying to punish the members of the metro community that live in Clark County,” Stober said. He mentioned the fact that I-84 and US 26 are not included in the congestion pricing service area. He pointed out that everyone knows the Sunset highway (US 26) and I-84 are major congestion bottlenecks and problems.

“It clearly communicates that this is about targeting people who live in the state of Washington and not about targeting the overall congestion problems that exist within the Portland metro area,” he said.

Nobody responded with the fact that the early phase of the program is a “test,” and that Oregon and ODOT’s ultimate goal is to toll all of I-5 and I-205 from “the border” with Washington. Later, Oregon hopes to expand the tolling to every major highway in the region, including I-84, I-405, US 26, and OR 217.

In April 2018, ODOT’s Mandy Putney briefed the Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council (RTC) on tolling programs. “Some of these scenarios might not raise much more than the cost to cover the operations of the tolling system,” she said.

Stober asked if people using I-405 would be tolled, to which he got a response of “no.” He sought further clarification, in that people driving south on I-5 would be tolled before getting on I-405. ODOT’s Lucinda Broussard responded that I-405 would not be tolled.

Stober pointed out a huge discrepancy in the program. Oregon says it’s about raising revenue to help reduce traffic congestion. C-TRAN is the only mass transit carrier to offer service on either I-5 or I-205, and yet Oregon law prohibits ODOT from sending any of the tolling dollars out of state. They cannot subsidize the only transit service that could help reduce traffic congestion, stated several members of the council.

Paulsen asked about the equity program. He couldn’t understand how it might translate into helping low income people. Congestion pricing “becomes something that’s viable only for those who have the means to take advantage of it,” he said. “It becomes disqualifying for those who do not have the means, so it’s very regressive in that respect.”

Broussard is ODOT’s dIrector of tolling. She shared that Oregon HB 3055 was recently passed which mentions a low income toll, but provided no details.

She shared the input would be coming from the ODOT Equity and Mobility Advisory Committee on tolling. That committee offers input for not only low income and minority communities, but also the BIPOC and other disadvantaged communities, according to Broussard. “Equity is not a one size fits all,” she said.

Broussard mentioned the equity program instituted for the Rose Quarter project. Yet the cost of that project has recently increased to possibly $1.25 billion. The Oregon legislature originally allocated $450 million in OR HB2017 which raises the question of who will pay.

Councilor Bart Hansen believes the widening of the Abernathey Bridge on I-205 will help reduce congestion, and therefore tolling to help pay for that is understandable. Tolling to pay for a new, presumably, wider Interstate Bridge is fair if it reduces congestion, according to Hansen.

“To simply charge folks in congestion mitigation to keep them off the road, I don’t see that as basically fair,” he said. “As Councilmember Paulson pointed out, you build a condition of roads for the rich. Folks that can’t afford it, well, they’ll have to make other options.”

Hansen recalled the last time ODOT presented to the council, he asked what is the benefit to Clark County? “They’re going to be getting time,” was the answer. “What immediately comes to mind is time for those that can afford it,” he said.

He also piggybacked on Stober’s remarks about the unfairness of C-TRAN not being able to be reimbursed for providing the only mass transit service across the river. “If I can’t afford to utilize the I-5 or I-205, (due to tolls), my next best bet when I’m in Clark County is going to be C-TRAN.”

Hansen lamented the fact that Clark County residents will be paying into the congestion mitigation program, but not getting the benefit of any funding to help the C-TRAN “Express” buses that are the only option for the low income people who must travel, to avoid the tolls.

During the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) debate, it was revealed that an estimated 60 percent of bridge tolls would be paid by Southwest Washington residents.

Mayor Anne McEnerny-Ogle addressed the equity issue of Oregon collecting tolling dollars from Washington residents, and not being able to share those dollars with C-TRAN. She said it would need a fix by the Oregon legislature.

She asked if low income people would be allowed a refund on the tolls?

“If we’re using C-TRAN to alleviate the congestion, how can we work to get those funds to support C-TRAN,” she asked.

Broussard responded: “we just need to go back and talk about how that all works.”

Brendan Finn runs ODOT’s office of Urban Mobility. He wrapped up by praising C-TRAN. “You do a very good job on the interstate there with bus on shoulder,” he said. “That’s something we want to see implemented more so here on our side of the river.”

With people expected to lose 69 hours stuck in traffic congestion by 2040, the ODOT officials did not say how much their tolling and congestion mitigation efforts would reduce that time lost in traffic jams.