Southwest Washington citizens are concerned about tolls that would fund Portland’s infrastructure

For the first six months of its existence, the I-5 Rose Quarter Improvement Project (RQIP) Executive Steering Committee (ESC) have focused on creating their “Vision and Values” statement and discussing community impacts.

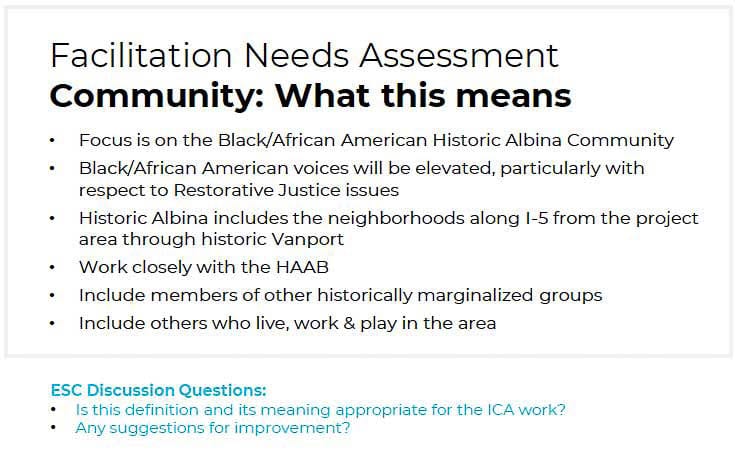

Key to those discussions was the negative impact the creation of Interstate 5 had on the minority communities in the Albina neighborhood and Vanport. The freeway bisected these neighborhoods creating a divide. The feeling is that this project can help heal the wounds created, as the two “highway covers” that will create real estate over the top of I-5 at the Rose Quarter, can reunite part of the divided neighborhoods.

This is of interest to the citizens of Clark County and Southwest Washington because Oregon is proposing to toll I-5 beginning “at the border” with Washington, in order to create a pool of money for their transportation projects, including potentially this Rose Quarter project. It was originally approved in Oregon HB2017 as a $450 million project. Two years later ODOT admitted the cost had ballooned to “up to $795 million” in part because they had failed to include inflation in the original cost projection.

The ESC met Mon., Nov. 23, getting an update on community involvement committees, and reviewing highway covers created around the nation. The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) is hosting an online Open House for citizen input regarding the project now through Dec. 6 (here).

ESC member and Metro President Lynn Peterson shared during the meeting that there is a $65 million funding shortfall due to the failure of voters to approve the $5 billion Metro transportation bond in November. “There was $65 million set aside in the regional transportation measure that failed. We will need to continue to pursue that funding on behalf of the City of Portland,” she said.

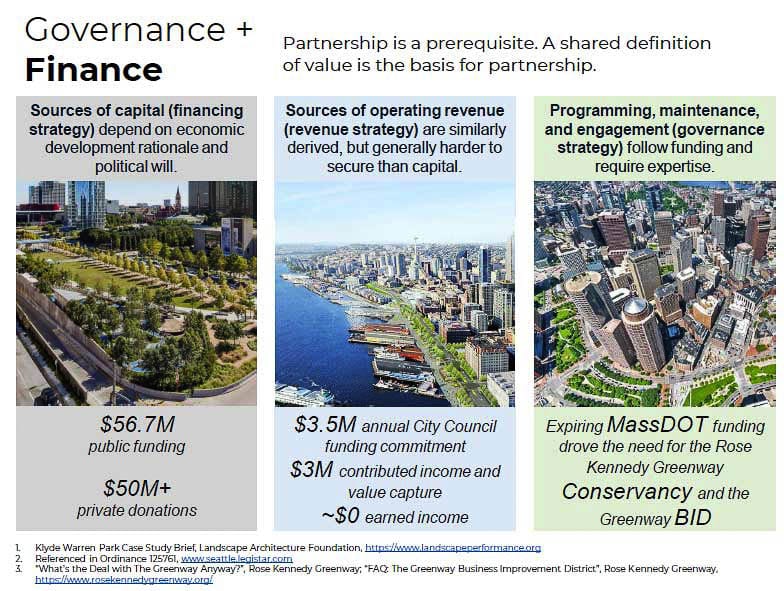

During the staff briefing about Governance and Finance, examples were provided of highway covers from around the nation. In every case, transportation dollars did not pay for the entire project.

“We should expect transportation money to be part of the solution, but not all of it,” said Candace Damon, an expert in urban redevelopment. She added: “highway cover projects are not the cheapest way to advance transportation objectives.”

Oregon Transportation Commission member Alando Simpson serves as chair of the ESC. He spoke of the divided community and the opportunity this project provides. “I think one thing that most of us need to keep in mind, that this is beyond complex, and more importantly, very emotional. Because there’s a lot of history with this.

“As chair, this very important project for our region in our state, in the West Coast for that matter, is to really use this as a way to bring us more together,” he said.

That divide appeared to widen at the end of June as the Albina Vision Trust withdrew its support for I-5 Rose Quarter earlier in the year. In response the Portland mayor and city council members withdrew support as well.

“This is a substantial investment that we’re all making, as taxpayers,” said Simpson. “The goal is that there is a return on that investment. We want to take into consideration human impacts based on infrastructure projects, and make sure that we’re not taking advantage of communities that don’t have the strongest voice.”

The ESC will create public input committees, including a Historic Albina Advisory Board (HAAB). It will be comprised of a maximum of 17 members. Additionally, there will be a Highway Cover Coordinating Committee (HC3). The HC3 will serve as the staff working group to support the Independent Cover Assessment (ICA) team’s independent development and refinement of the three development scenarios.

Citizens might wonder how all these government created committees will serve to improve transportation in the Rose Quarter area of Interstate 5 and the legality of spending transportation dollars for community redevelopment. The Rose Quarter is congested 12 hours a day according to ODOT.

In response to public comment and input, the project team modified the southernmost portion of the project to avoid impacts to the Esplanade and avoid construction activities on the east bank of the Willamette River.

The ESC was shown slides of numerous “highway covers” from around the county. Some had nice open parks and public spaces. Others had office buildings and development on them. Local citizens might be aware of the Seattle Convention Center, built on top of an I-5 cover in downtown Seattle. Other examples are the covers over I-90 on Mercer Island or several smaller covers on Highway 520 in Bellevue.

Some of these highway covers were funded primarily with taxpayer money, but others included substantial contributions from private funds, in public-private partnerships (P3). They included Klyde Warren Park in Dallas with $56.7 million in taxpayer funding and over $50 million in private money. Other projects included two in Boston and two in New York City, and the Seattle Alaskan Way Viaduct.

Damon briefed the committee on Governance and Finance issues.

“When we talk about Governance and Finance, we’re really talking about three things,” she said. “First, how does the initial design and construction get paid for? Second, how does what we put on the lid get maintained over time so that it delivers on the promises that were made? And third, who is it that is organizing the coalition of stakeholders in order to design, build, and maintain the investment over time?”

Damon pointed out “in every case, there’s no single source of funding, and there’s no unified governance structure.” In Dallas, the DOT put up about half the money for their project and private donations funded the balance. She also pointed out “the cautionary tale” of Boston and what became known as “the Big Dig” where the Massachusetts DOT was forced to contribute significant funding. The $21 billion “Big Dig” was the most expensive highway project in the US, outside the interstate freeway system.

In the Seattle Alaskan Way Viaduct project, they decided not to go to the statehouse “because we didn’t think we’d win,” said Damon.

ESC member Marlon Holmes of N/NE Housing Strategy weighed in. “This is the first time I’m hearing about the cost of funding coming from anywhere but ODOT,” he said. “Am I mistaken that this project would be fully paid for by the state and not any cost being incurred by the City of Portland? Is Portland paying for any of this or it is all being funded by ODOT?”

Chair Simpson responded by referencing the community engagement process as being critical, and what is created in a “complex, massive development” in a project like this. He mentioned “coalition building when you’re trying to raise significant price tag projects, or several projects in one.”

“I think the whole premise as to why we’re doing this is so that we can kind of kind of create that infrastructure, so that if it becomes a $100 billion project, that’s something the entire community says this is what we want, this is what we need,” he said.

“I think it should be known to the community because I didn’t notice that this project isn’t just going to be funded by ODOT,” said Holmes. “That money has to come from other places. Because I’m quite sure if I was under the impression that this whole thing was being taken care of by ODOT, that quite a lot of other folks are probably thinking the same thing too.

“So it should be out there that funds for this big project is going to have to come from other places besides just ODOT,” he said. “Because then we might start hearing a lot more voices.”

That prompted an extensive and important response from Damon.

“The first question is what is the project? So I can certainly imagine a world in which this group and its friends and colleagues and allies exert enough political power to get ODOT to make 100 percent of the capital investment,’’ Damon said. “Whether that is plausible or not, you guys probably have a better idea than I do.

“But then something presumably goes on top of the cap,” she said. “And that something is more or less public, it is more affordable, more locally owned, or it isn’t. It’s big towers that are developed by national developers. What that program is, what the project on top of the cover is, starts to suggest who might pay for its long term maintenance, and how involved the community will be over time.

“So that’s very much a focus of the scenario development that follows and our ongoing conversations with you,” she said. “I don’t think anybody on the consulting team has the notion that either the capital, the operating the program, or the governance will be one way or another way.

“We’re simply pointing you to a set of national precedents that suggest that very expensive investments that are about more than just transportation usually require people other than just the transportation people to come to the table,” Damon concluded.

Peterson responded by mentioning the funding hole created by the failure of the Metro transportation bond. “We can’t just have a lid and not have it connect to the surface streets on each side,” she said. “There was $65 million set aside in the Regional Transportation measure that failed. We will need to continue to pursue that funding on behalf of the City of Portland.

“The entirety of the project doesn’t work without that surface street improvement, as well as the undergrounding of the light rail for the future,” she said. “That was also in the package. There are a bunch of things that were surrounding this project that are part of the transportation system of this place. We need to find financing for those.”

Peterson closed by reminding the ESG that Portland has never been able to realize a public-private partnership of the scale shown as examples. “Being able to get to that level means bringing in partners pretty early and often to be able to have the private side be part of the design, as well as the financing governance of it,” she said.

That prompted Jana Jarvis of the Oregon Trucking Association to weigh in. “This conversation has been enlightening. It’s my understanding that all covers are not created equal. Depending on what you’re going to put on top of it changes the design standards and therefore the cost of building the cover.

“We also need to recognize that we have some limitations on the use of Highway Trust Fund dollars and in how they’re used,” she said. “As was mentioned earlier, ODOT is not in the community development business per se. I think it’s really helpful for us to get a vision of what it is we think we want to have, and then have a better understanding about how in the world we’re going to pay for it.

“As I was listening to the presentation, I was a little concerned, too, because I think there’s this thought out there that ODOT is going to be paying for everything,” she said. “And that has not been my understanding from day one. So I wanted that clarified please.”

Simpson said Jarvis was “one hundred percent correct.” He indicated a small pushback, in that ODOT “can build or be one element, one piece to building community. But it’s not designed to build entire communities, especially as it relates to Urban Development.”

He closed by saying this opened up a very important dialogue and conversation for upcoming meetings. Other members of the ESC agreed.

TriMet’s Doug Kelsey shared with the ESC that there is a tremendous amount of work and “heavy lifting” required to deliver the public-private partnerships that could help pay for some of the more elaborate types of projects they were shown. That would require a significant amount of time, and capital up front.

Metro’s Peterson reemphasized the lack of resources on the local side. “We are in a (financial) hole in terms of being able to be a partner and we’re gonna have to figure out how to move that forward.”

“I don’t think it’s fair to put the entirety of what we’re doing on the City of Portland,” she said. It’s a regional issue. That’s why we put it on a regional agenda.”

When citizens hear “it’s a regional issue” it likely raises concerns about tolling dollars and other funding mechanisms being used to pay for the highway caps and community development of Portland. Clackamas County and Washington County rejected the Metro transportation bond in November. Southwest Washington citizens are extremely concerned about tolls and paying for Portland’s infrastructure.

According to ODOT’s “Cost to Complete” report, in order to maintain the project’s current delivery schedule and begin main construction in 2023, a final decision regarding the expanded highway covers must be made no later than June 2020. Preliminary estimates suggest a range of $200 million to $500 million of additional cost to design and build expanded covers.

The next ESC meeting will be Dec. 14.