The provider could soon ramp up to nearly 10,000 tests per week using a new PCR testing platform

VANCOUVER — It was the image very early in the pandemic that had everyone cringing.

A patient, head tilted far back, winces as a nurse clad head-to-toe in protective gear shoves an obscenely long cotton swab deep, deep into the nose.

As unpleasant as that scene was, public health officials will say it happened far, far too infrequently early in the pandemic to be of much use in actually mitigating the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19.

Even as the virus spread around the globe, filling up hospitals in Italy, Spain and New York, health providers struggled to get their hands on supplies to do much testing, and laboratories worked around the clock to increase their ability to analyze the tests they were receiving.

Things have vastly improved since then, with the United States now averaging nearly 1.9 million daily COVID-19 tests, according to the Covid Tracking Project, more than doubling since July.

In Clark County, testing numbers rose to over 7,000 a week in early October, before dropping to fewer than 5,000 later that month, then climbing back to 7,509 for the week of Nov. 8.

That number could climb much higher by the end of the year, thanks to a new testing platform obtained by The Vancouver Clinic.

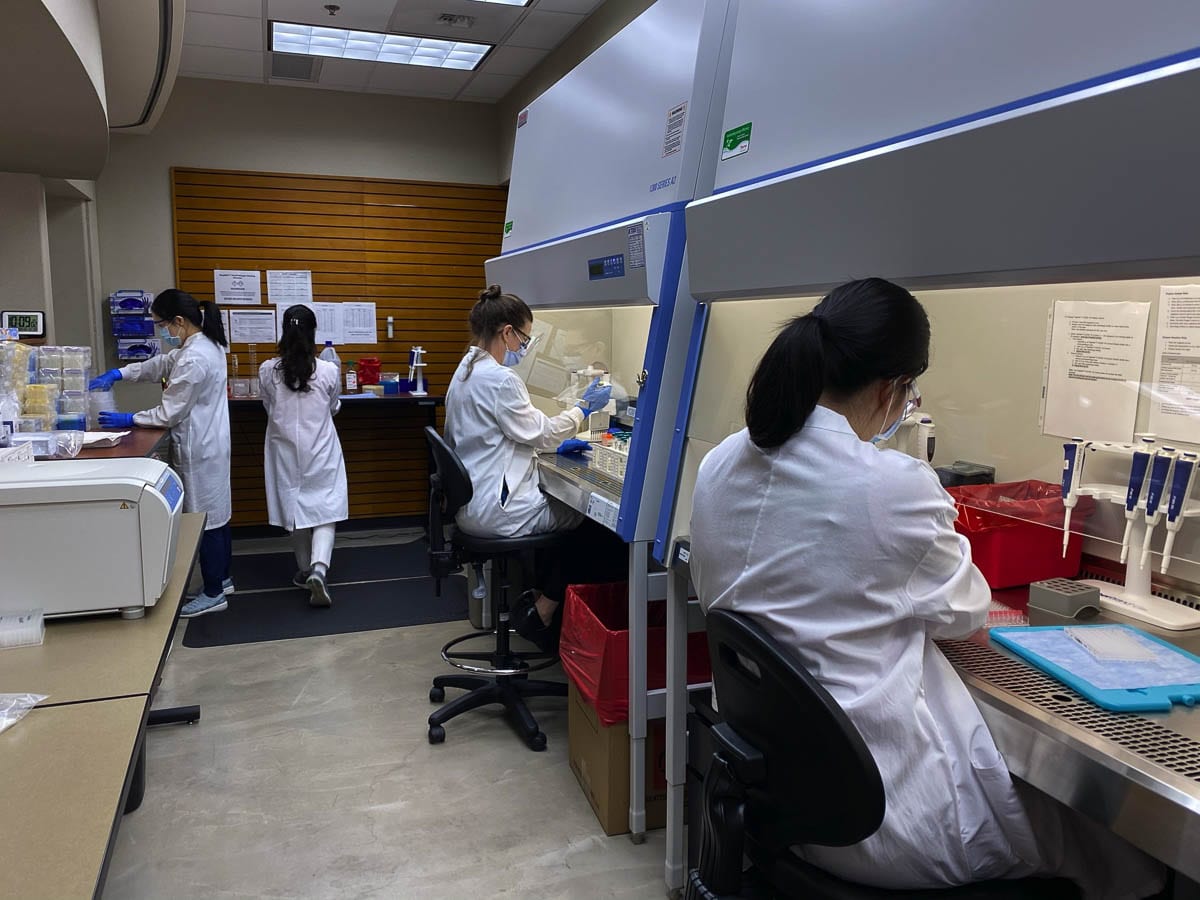

Despite accounting for around a third of the Clark County health provider market, The Vancouver Clinic was responsible for nearly 90 percent of the COVID-19 testing early in the pandemic, due largely to their aggressiveness in acquiring point-of-care rapid testing machines made by Abbott, along with a BD Max PCR testing system by BD Molecular Diagnostics.

Those machines, however, were plagued by two main problems. The Abbott machines, which look for antigens in the blood, are quick, but also more prone to false positives. The BD Max machines required a proprietary reagent (the fluid which preserves the specimen), and keeping enough supply proved difficult.

“Throughout this whole pandemic for the past year, we’ve really been playing almost whack-a-mole with which problems are we going to solve this week,” says Jon Wilson, lab administrator for The Vancouver Clinic.

“If you have the machine but then you can’t get the reagents necessary to do the test, it doesn’t do any good,” adds Chief Medical Officer Dr. Alfred Seekamp.

Which is why The Vancouver Clinic made the decision to invest in a new testing platform, the TaqPath, by ThermoFisher Scientific, uses a generic reagent, making that much less of an issue.

That doesn’t mean everything has gone smoothly, however.

“Plastics, your pipette tips, as well as some of the swabs and collection devices now seem to be the barrier,” says Wilson.

Hiring has also been difficult, given the exacting qualifications required to run the testing equipment.

Still, once those problems are ironed out and everything is fully operational, Seekamp says they expect The Vancouver Clinic alone could run nearly 10,000 tests a week.

“When you have more testing available, you’re able to make the interventions sooner, whether that be quarantining or other methods,” says Seekamp. “So I think from a public health perspective, more widespread testing would be a benefit for our community.”

But having more testing isn’t of much use if it can’t be relied on.

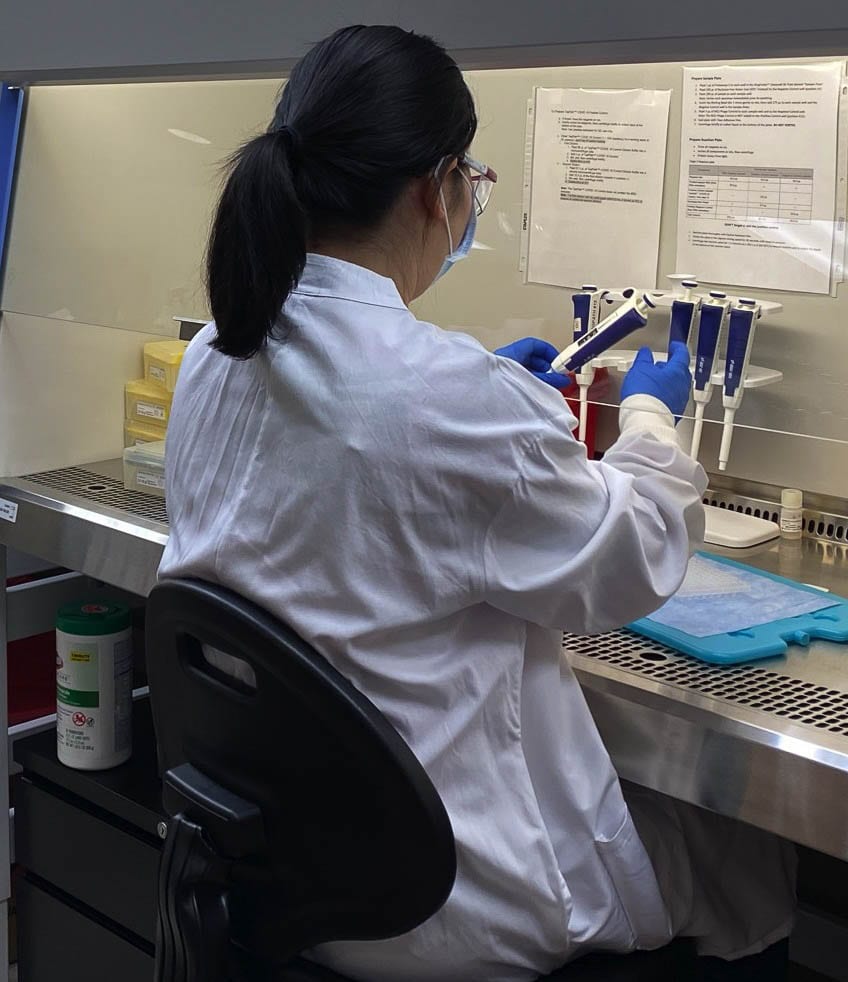

Recently, greater scrutiny has been given to how PCR tests are run, especially focused on the CT Value, otherwise known as the threshold cycles. That represents how many cycles a test sample is run in order to eliminate “noise” or background signals and determine if there is enough of the virus’ genetic material to generate a positive result.

Too few cycles, and the test results can be highly unreliable. Too many, and there is concern that non-consequential amounts of the virus could trigger either a false positive, or else a positive result for someone who is not, in fact, contagious.

“The CT value for this instrument is up to 37 for it to be considered a positive,” says Wilson, “which is a really good indication that it’s accurate.”

“It’s more specific and it’s more sensitive,” adds Seekamp, “so we’re picking up more true positive cases of COVID-19.”

That greater sensitivity is also accomplished by the use of molecular “markers” to sniff out signs of the virus.

“Having three molecular markers does give us a lot of confidence that this is a good test,” Wilson says. “As well as independent research studies that have shown that this matches up really well with other platforms.”

Each test is also accompanied by a known negative and positive sample as controls, to make sure the machine is operating correctly.

Greater testing availability, said Seekamp and Wilson, could help public health officials and healthcare providers to do more frequent testing of people on the front lines of the pandemic, or people who are in contact with high risk populations. It could also be used for people needing to travel out of state, or once they return.

While the TeqPath platform will become their primary system for testing, Seekamp says the BD Max and Abbott machines are still useful, since they can take advantage of different supply chains.

“We have been able to kind of hedge our bets as a community,” he says, “to supply testing where it’s needed the most.”

That capacity, Seekamp adds, will likely be needed for quite some time yet.

“Until there’s really widespread immunity, either natural or from a vaccine, we’re going to continue to need to use COVID testing as part of our armamentarium,” he says.

While The Vancouver Clinic still accounts for around 60 percent of the COVID-19 testing done in Clark County, Seekamp says he’s been impressed to see how the other hospitals, including PeaceHealth Southwest and Legacy Salmon Creek, have banded together to tackle the pandemic.

“We always try to look for silver linings in a pandemic,” he says, “and I think that one of them is that we have developed a very close working relationship that will endure and continue after COVID-19 is a distant memory.”