Two different mindsets about transportation solutions, but Oregon is focused on light rail and Interstate 5

As citizens watch and participate in the various “community forums” created by the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project (IBRP) team, they may not be aware of what other ideas have been proposed over the years, when they were proposed, and why they were rejected. The most recent effort known as the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) failed in 2013 when the Washington legislature refused to fund the state’s share of the project.

The CRC was a $3.5 billion “light rail project in search of a bridge” according to an Oregon Supreme Court Justice. It had $8 tolls and would provide only a one-minute improvement in the morning, southbound commute. It was labeled a bridge too false by one media outlet.

Over $200 million was spent on the CRC, of which it is reported $140 million must be repaid to the federal government if something isn’t built. While that was disputed by economist Joe Cortright, legislators from Oregon and Washington created a Bi-State Legislative Committee to restart the process.

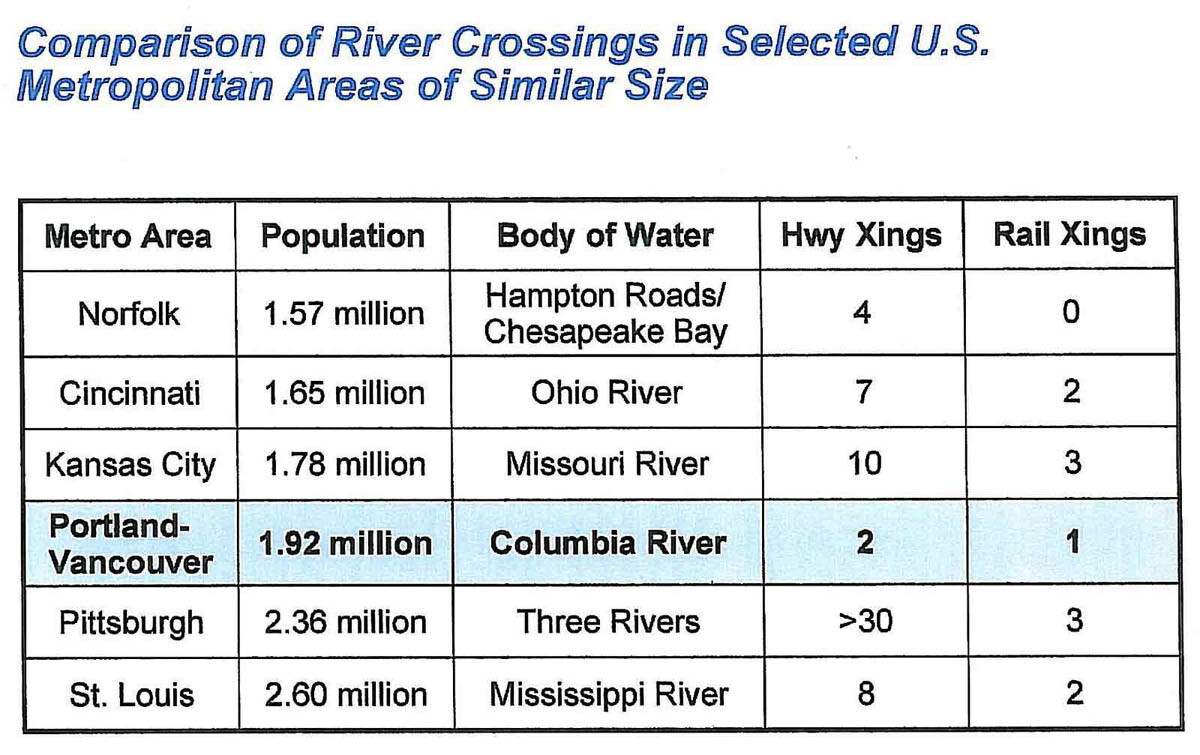

The most current data available (2018) shows 73,240 Clark County residents paid $236 million in Oregon income taxes. Another 46,890 Washington residents paid $128 million. Many of those taxpayers from Southwest Washington commuting to Oregon and stuck in traffic want significant traffic congestion relief. They would like more than two ways to cross the Columbia River. After all, Portland has a dozen bridges across the Willamette River.

Chuck Green is one of the more experienced persons in Clark County regarding transportation projects and the history of discussions between the two states. He served as a project manager for C-TRAN’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Vine. Green recently shared the following on social media.

“The I-205 Bridge was opened almost 40 years ago. Since that time:

Clark County’s population has grown 261 percent

Cross-Columbia River vehicle traffic has grown 239 percent

Cross-River Transportation Capacity has grown 0 percent

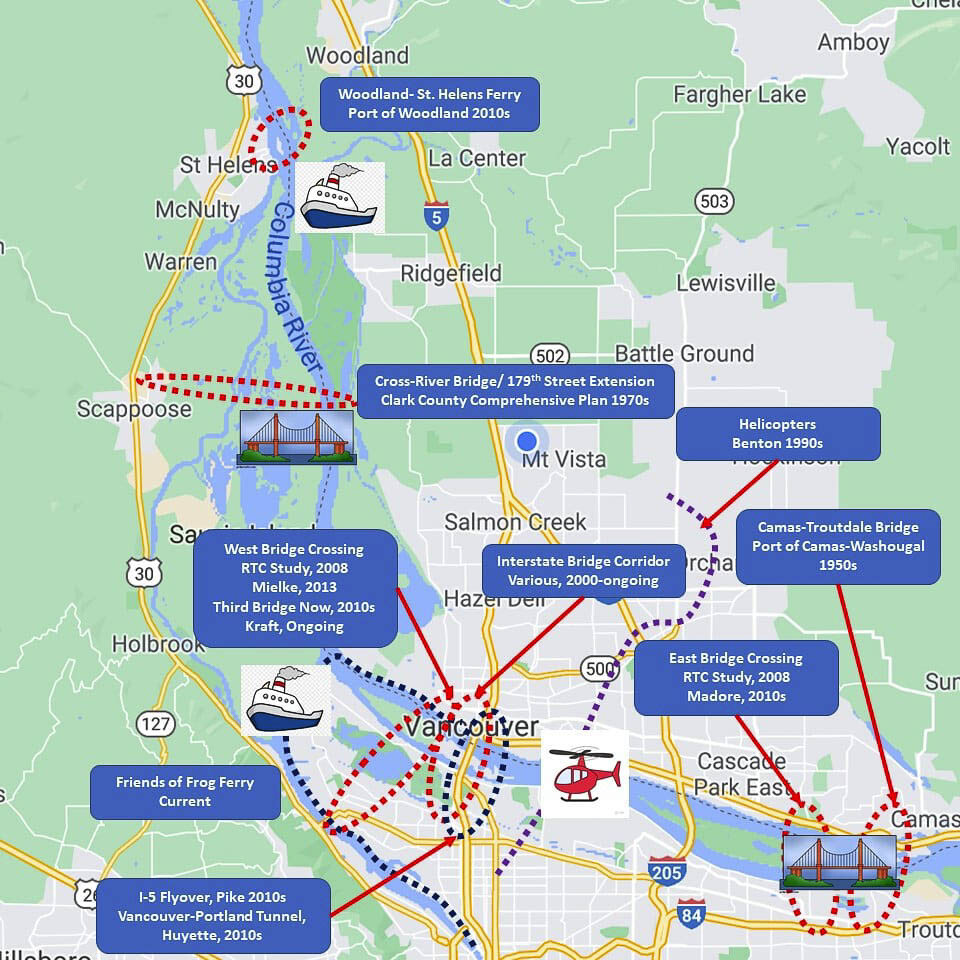

“I went back into my database to look at all of the ‘good ideas’ for new transportation capacity between Oregon and Washington since the 1950s, in the sense of ‘a new (bridge, tunnel, tram, train, boat) between Oregon and Washington would be a really good idea, don’t you think?’

“Since the 1950’s, there have been over 20 ‘good ideas’ about some new cross-river, bi-state connection. Other than the second I-5 bridge span and the I-205 bridge, both of which were planned and funded by the federal government, how many of these ‘good ideas’ have been implemented?

“Zero.

“Other than the Frog Ferry, which is a recent proposal by a Portland group, how many of these good ideas were proposed by Oregonians?

“Zero.

“Other than the I-5 bridge replacement/ Columbia River Crossing project, how many of these “good ideas” are on any adopted transportation plan?

“Zero.

“So, I present to you, the ‘road to good ideas’ proposed over the years here in Clark County.’’

Green and his graphic tell an incredible tale of ideas proposed, but never implemented. The only time Washington citizens appear to have said “no,” was to the failed CRC.

Green can be forgiven in over simplifying by saying other than Frog Ferry, zero of these “good ideas were proposed by Oregonians”. That’s not completely true. Two come to mind.

Former Oregon Rep. Rich Vial proposed and introduced into the Oregon legislature a bill in 2017 for a westside bypass. He offered two possible routes, a price tag of $20 billion, and it included a public-private partnership with tolls to cover the costs. It never got a public hearing as the leadership let the bill die.

Sharon Nasset is an Oregonian behind the “3rd bridge now” group. Their proposal is for a western connector to the Port of Portland and US 30, and another connection down to Swan Island.

Nonetheless, the overwhelming majority of the ideas in Green’s graphic had their largest number of proponents coming from the Washington side of the river.

In 2017, Rep. Liz Pike held three transportation town hall events. She gathered a group of citizens from the private sector offering a variety of solutions. Some were updated versions of earlier proposals; others were new.

Transportation architect Kevin Peterson set the stage, describing the CRC traffic projection numbers, and the differences between the Portland and the Clark County mindsets regarding transportation. (Video here).

Practical Design Fly-over near I-5

Dave Nelson, presented his Practical Design Fly-over suggestion, for creating an express lane bridge connecting north Vancouver to Delta Park. This project would provide four lanes in each direction over I-5, plus new SR 14 ramps in the form of a 2.2-mile bypass of Marine Drive, Hayden Island and the existing I-5 Bridge.

The project would convert the Interstate Bridge to local access and be replaced in the future with an at-grade local access bridge with lift span. It would also move the ship channel to the center of the Columbia River to avoid 95 percent of the bridge lifts.

Nelson revealed that the Dean of the WSU engineering department had examined the CRC proposal with his engineering team and found it was not buildable. How is that possible when WSDOT and ODOT were providing oversight of the CRC’s management and consultant team?

Cost estimates for this project were $1.5 billion. (Video here).

Tunnel below I-5 corridor

Bill Huyette proposed building a new tunnel below the I-5 corridor. The project would create a 7.8-mile tunnel from Leverich Park in Vancouver to the 1-5/I-405 cuplet in Portland. It would add two lanes in each direction and be a “massive freight mobility improvement, and greatly improved commute times,” according to Huyette. The existing I-5 Bridge would remain open and be upgraded and improved.

Highlights included that it would be privately designed, financed, built, owned, operated and maintained through a Modified Private-Public Partnership. (Video here).

The project would require minimal traffic/community disturbance during construction, minimal environmental impact, minimal right-of-way acquisition and minimal time for construction — three years under construction and total completion in four years. Huyette’s cost estimate was $4.5 billion.

West Express Bridge Tunnel

Bill Wagner offered a proposal for a new West Express Bridge/Tunnel crossing over the Columbia River. One estimate stated that this project could cost as much as $20 billion and take as many as 35 years to complete.

The West Express is an eight-lane limited access corridor with three express lanes in each direction, flanked by dedicated high-speed merge and exit lanes and featuring an elevated 20-mile bicycle and pedestrian path with horizon views of rivers, wetlands and the Cascade Mountain range.

The project would be built in five phases: Phase 1A and 1B, Vancouver to west Portland; Phase 2, west Portland to Beaverton/Hillsboro with tunnel under Forest Park; Phase 3, new 192nd Avenue Bridge to OR I-84; Phase 4, seismic retrofit of I-5 Bridge; Phase 5, Vancouver to I-5/north Clark County via Fruit Valley Road. (Video here).

East County Bridge

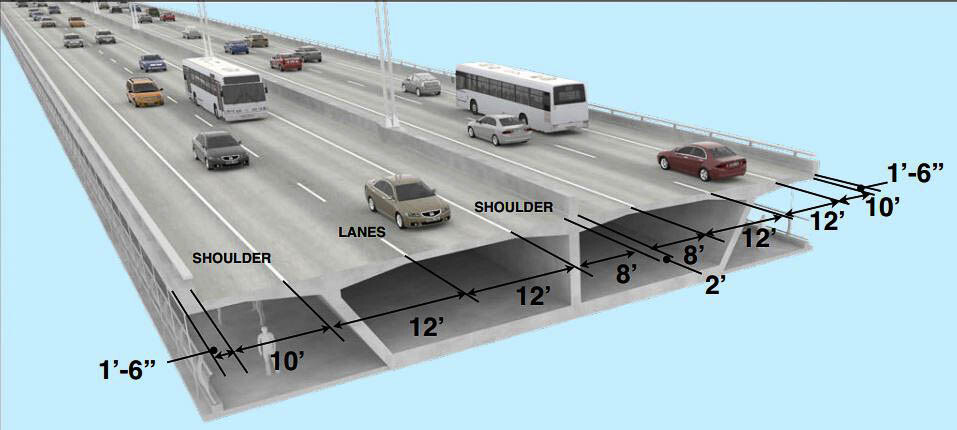

The cheapest of the five proposed options, at an estimated cost of $800 million (in 2017), would be a new East County Bridge, located east of the I-205 Glenn Jackson Bridge. It was offered by Linda Figg of Figg Bridge Builders,

This project would provide four new highway lanes, two northbound and two southbound. The bridge would have wide safety shoulders — 8-foot inside and 10-foot outside in each direction. There would also be two, 12-foot multi-use protected pathways for pedestrian and bicycle experiences.

The bridge would be built with long spans to accommodate river traffic and would provide navigational clearances for Columbia River vessel requirements. It would also have gradual grades for better truck speed and mobility. (Video here).

Cascadia Commuter Express/Cascadia High Speed Rail (CHSR)

Brad Perkins shared a Cascadia High Speed Rail project that would go from Eugene, OR. to Vancouver, B.C. He is co-owner and president/CEO of Cascadia High Speed Rail, LLC.

The portion of this project crossing the Columbia River would be a $1.7-billion cost for a new multi-modal bridge, 1.2-mile tunnel, 11.3 miles of corridor and three auto interchanges. The multi-modal bridge is double-decked west of the existing BNSF Freight Rail Bridge.

The top deck has four lanes for vehicles. The bottom deck has two tracks for freight trains, two tracks for Cascadia Commuter Express/CHSR.

The Cascadia Commuter Express corridor will span from the Rose Quarter Transportation Hub to a platform stop in west Vancouver and a platform stop at 78th Street and Fruit Valley Road in Hazel Dell.

The 11.3-mile Cascadia Commuter Express trains could move 16,000 passengers per hour. Trip time between Portland and Vancouver would take six minutes and Portland to Seattle in 80 minutes according to Perkins. (Video here).

Government studies on new corridors

A review of numerous documents provides the following information. Here’s some history on third bridges and transportation corridors studies.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s, metro planners identified the need for BOTH the I-205 corridor and a western bypass. They created a map showing the location, and planned to build the western bypass once I-205 opened in 1982. The “ring road” was to be completed by 1990. Sadly, politicians refused to build the western bypass.

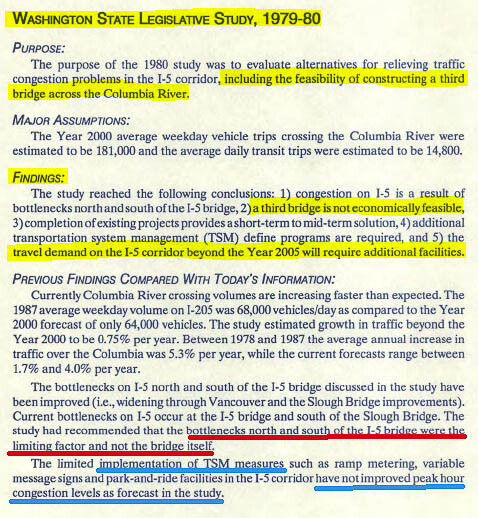

In 1977-79, a Washington legislature study found: “Without a new crossing, the I-5 bridge would be overloaded 30% beyond its capacity by the year 2000.” Their report included five possible locations for a third bridge.

A 1980 Washington legislature study concluded: “travel demand on the I-5 corridor beyond the year 2005 will require additional facilities.” It furthermore stated that “bottlenecks north and south of the bridge were the limiting factor and not the bridge itself.”

A 1980 Oregon & Washington Governor’s Task Force said “a 3rd bridge would not increase the capacity for interstate travel unless it were accompanied by a new corridor north and south of the Columbia River.” The technical analysis concluded that “the region would not have to revisit the question of additional river crossings until 1990.”

Additionally, that same study recommended “bottlenecks north and south of the I-5 bridge were the limiting factors and not the bridge itself”.

The 1980 Bi-State Study forecast 185,000 cross-river daily vehicle trips in 2000. A 1988 study showed I-205 traffic had already exceeded the 2000 forecast. WSDOT reports over 300,000 daily crossings prior to the pandemic. That 1988 study also discussed the benefits of TWO new bridge crossings, one west of I-5 and one east of I-205.

A 1988 Bi-state study found the following: “A crossing west of I-5 would provide some traffic relief to I-5 and would provide direct access to the growth centers of Washington County and the port activities in Rivergate and Vancouver.” It also addressed an additional eastside transportation corridor.

It reported: “current (1988) I-205 traffic data show that Year 2000 forecast on I-205 has already been exceeded” – that is 12 years ahead of predictions. Furthermore, the 1988 study concluded: “The higher percentage of traffic to Clark County can be expected to lead to more severe traffic congestion problems than anticipated in the Bistate Year 2000 forecast.”

In 2007, Matt Ransom (now RTC Director) and a Transportation Corridor Visioning Project “Think Tank” held multiple meetings. Their goal was “potential westside and eastside new regional corridors including potential new crossings of the Columbia River.”

In 2008, the RTC produced their “Visioning Study” identifying the need for two new transportation corridors by the time Clark County population reached 1 million people. Twelve years later, they have no new transportation corridors in their 20-year plan for 2040.

In August 2019, the RTC Board conducted a review of the “Visioning Study”. Roughly a dozen citizens showed up offering public comments in support of a third bridge and transportation corridor. This number of citizens showing up to an RTC Board meeting is extremely rare.

The current RTC traffic congestion report states the Interstate Bridge reached peak capacity in the early‐1990s; and the Glenn Jackson Bridge did so in the mid‐2000s.

At the first Bi-State Bridge Committee meeting of Oregon and Washington legislators in the fall of 2018, Rep. Ed Orcutt (Republican, 20th District) asked the legislators to tie any replacement of the Interstate Bridge to a new, 3rd bridge across the Columbia River.

John Charles of the Cascade Policy Institute shared the following:

“I agree that the current I-5 bridge is perhaps functionally obsolete, but I don’t think replacing it or rehabbing it is a huge priority now. It is functional. I think it needs to be part of a package deal. I simply reiterate the comments Representative Ed Orcutt made and Representative Rich Vial — you need more capacity. I would bump the I-5 replacement to maybe something you do after 2030 or 2035. No bridges are going to fall down.

“You absolutely need a third, fourth, and fifth bridge. You should think bigger. The same reason that we have about a dozen bridges over the Willamette River in downtown Portland. The St John’s bridge is not the same as a Sellwood or the Markham or the Fremont or the Hawthorne (bridges). They all serve different travel markets and they’re all really important.”

It would appear that many, many citizens have offered multiple ideas for additional transportation capacity connecting the two states. Green’s map is an excellent “one picture is worth a thousand words” of so many ideas that transportation planners and politicians refused to embrace.

This is well over 40 years of “discussion” and study.

Regional population has doubled since the 1982 opening of the I-205 transportation corridor, 38 years ago. That would seem to strongly support the need for multiple new bridges and transportation corridors with many possible “solutions” that add transportation capacity.