VANCOUVER — The plan was to step to the side, away from the casket, as soon as they had folded the flag that day at Arlington National Cemetery.

Instead, they stood at attention for 25 more minutes.

“In that time, it struck some of us,” said George “Bud” Barnum. “We had just buried our Commander in Chief.”

It has been more than 53 years, but Barnum can still cite just about every detail regarding his four days with John F. Kennedy.

From being there at Andrews Air Force Base when Air Force One arrived from Dallas with the president’s body, to the morgue at Bethesda Naval Hospital, to the White House, the Capitol, the cathedral, and finally Arlington.

Barnum, 24 years old at the time, was there every step of the way, carrying the casket with other servicemen in the honor guard.

The former Vancouver resident has started sharing his experiences with larger audiences. In town recently for a grandson’s graduation from Skyview High School, Barnum spoke at a meeting of the Portland Executives Association, which led to an interview on a popular Portland radio show.

Bud Barnum is the father of Bruce Barnum, the head football coach at Portland State University. Bruce has a regular appearance on the Bald Faced Truth radio program (102.9 FM/750 AM The Game) hosted by John Canzano. Earlier this month, Bud Barnum joined his son in studio.

Soon after, he sat down with ClarkCountyToday.com to give his account of those four days in 1963.

While he does not need notes to recall the details, he is grateful that his supervisor required him to write an account of his experience. On Nov. 29, 1963, a week after the death of the president, Barnum typed 16 pages of memories. For this story, the quotes in italics are from those notes, while his other recollections are from our interview last week.

Barnum was a yeoman second class in the United States Coast Guard, assigned to the Coast Guard’s headquarters in Washington D.C. when he was selected for honor guard detail. At the time, the Coast Guard did not have its own honor guard, so he worked with U.S. Army soldiers at nearby Fort Myer, part of the Old Guard to conduct memorials. For state funerals, an honor guard has representatives from all branches of service. While many would call them pallbearers, in the military they were officially referred to as body bearers.

That fall, Barnum was on one of two teams rehearsing and learning the protocol of state funerals in preparation for the death of President Hoover. The 31st president, who was in poor health at the time, would live until the following October. The men of the honor guard, though, would be called to action the night of Nov. 22.

Official word arrived that President Kennedy had died. Non-essential personnel were told they could leave for the day. No one told Barnum he would be on call. In fact, even though he had been training, he had no experience with burial detail.

“I had never even participated in a civilian funeral at that point,” he said.

He figured it would be members of the other team who would receive this assignment.

Barnum went home, shocked by the news, just like the rest of the country. His home’s location would end up putting Barnum in the middle of the nation’s mourning.

Due to the chaos in the nation’s capital, which included a major traffic jam, honor guard supervisors were concerned about getting everyone in place for the arrival of the president’s body. So they called those who lived closest to Andrews Air Force Base.

“That’s how I was picked,” Barnum said.

—

A career in the service required several moves for Bud and Sally Barnum. His final assignment with the Coast Guard, in 1978, brought them to Vancouver to live while Bud worked on Swan Island in Portland. After retirement from the guard in 1980, the two remained in Vancouver for another 14 years, raising their family. Their sons graduated from Columbia River High School.

While they now live in Lake City, MN., in terms of length of stay, Vancouver is “home.”

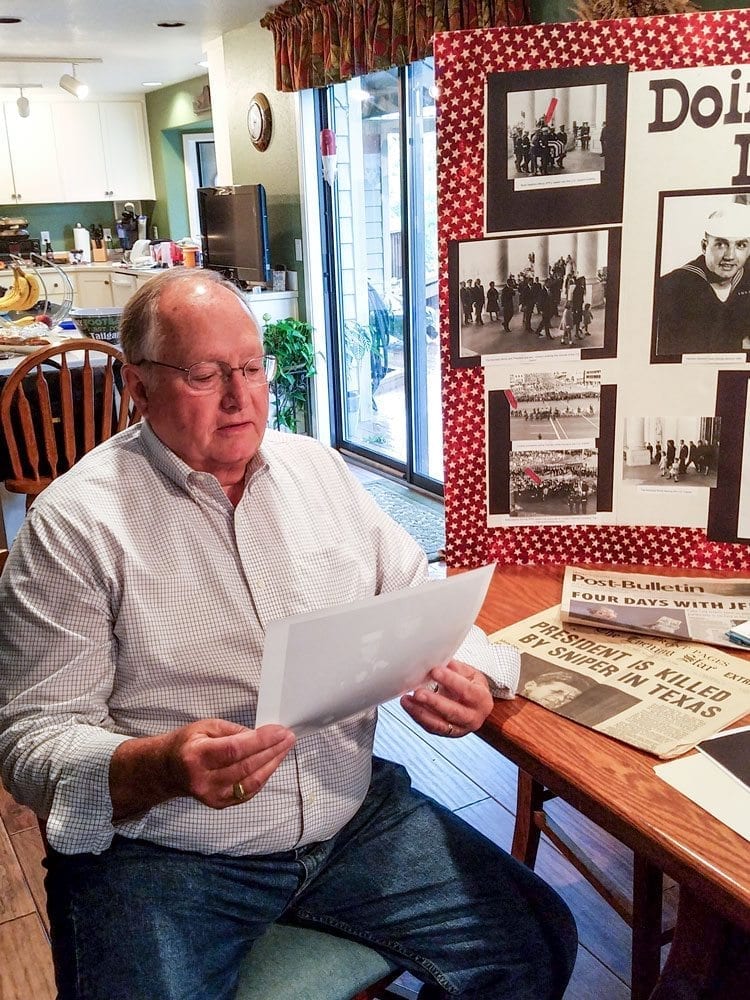

Two grandsons are part of the Skyview community. Brody Barnum graduated this month. Cooper just completed his freshman year. As an eighth-grader, Cooper did a school project on his grandfather.

“It was really cool to get to know how important he was in that situation,” Cooper said. “I did a lot of research on him. I called him every day on the project.”

Years ago, when Bruce was in middle school in Vancouver, one of his teachers thought Bruce was trying to pull a fast one. Bruce recalled the teacher telling him to stop making up stories about JFK.

Cooper’s assignment had all the documentation and pictures.

“My closest friends would say ‘What? Really?’ Yes, my grandfather did this,” Cooper said.

His poster showcasing his grandfather was a hit.

“It was definitely one that caught your eye,” Cooper said.

—

The chaos continued when Air Force One landed at Andrews. Barnum and his fellow honor guard members were there, ready to execute their mission, to take the casket off the plane. Instead, the secret service intervened. The honor guardsmen were flown by helicopter to Bethesda Naval Hospital, while the president’s body was transported in an ambulance.

At Bethesda, the honor guard performed its first task, carrying the casket from the ambulance to the morgue.

To this day, Barnum still receives inquiries from conspiracy theorists.

“All the time,” he said. “All the time.”

Several people believe the president’s body was switched during this confusing time.

As far as the conspiracy theories of what happened in Dallas — did Lee Harvey Oswald act alone? — Barnum has no expert analysis.

“I don’t have any more idea than you do,” he said.

But he knows it was John F. Kennedy at Bethesda.

“All I can say is he was the one laying on that slab,” Barnum said.

From there, the honor guard moved the president to a hearse for transport to the White House and carried the casket inside the White House.

Jacqueline Kennedy followed the guard into the White House, around 4:30 a.m. Nov. 23.

“She was still dressed in that pink outfit, with the blood,” Barnum recalled. “It was the only time I saw her break down.”

The men of the honor guard returned to Fort Myer. Once there, they were told they would take care of the president through the burial. They had one request.

The original six needed all of their strength to carry the casket from the hearse to the White House. There are varying estimates of the weight of the casket, but with JFK’s body, most agree it was more 1,000 pounds.

“We soon realized we couldn’t carry this,” Barnum said.

Two more body bearers were added to the team. In all, there were two soldiers, two marines, two sailors, one airman, and Barnum, representing the Coast Guard.

The honor guard moved the president from the White House to the caisson for the solemn journey to the Capitol building. Barnum and the guard can be seen in photographs and news footage of that day, following the caisson.

After lying in state in the Capitol for a day, Kennedy was moved to St. Matthew’s Cathedral on Nov. 25 and then to the gravesite at Arlington.

That final march was about 3 miles, Barnum said.

In between all the moves, the honor guard would continue to rehearse. They used the stairs near the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington to practice, keeping the casket level. They filled another casket with sandbags and had another soldier ride on top, trying to simulate the weight of JFK’s casket.

The guard went over the final ceremony a few times, including the folding of the flag.

They were professional servicemen. They trained for excellence.

“It didn’t just happen,” Barnum said. “We were doing our job. That’s all. We weren’t thinking of the occasion or the ramifications. We were just trying to do the best job we could do.”

From the honor guard’s perspective, the ceremony was a successful mission.

Within a year, Barnum would be on the detail for two more state funerals. Gen. Douglas MacArthur died in April, 1964, and President Hoover passed that October.

Barnum said he had no idea back in 1963 that he would still be talking about those four days. There was more interest in his story at the 50th anniversary of JFK’s death than the 25th, he added.

“To this day, I still get people sending me stuff to autograph,” he said. “I’m amazed that people are this interested in it.”

Lately, it has been people from Belgium and Australia, of all places, who have been contacting him.

Plus, there are the conspiracy theorists. He has had to cut off some people.

“I find it difficult not to get confrontational with some of the conspiracists,” Barnum said. “They want you to say what they want to believe. There are some I won’t talk to.”

The mass of people at the funeral kept the “Joint Body Bearer Team,” as the Army described the honor guard, in place soon after the flag was presented.

Again, the plan was for them to exit quietly. There was no pathway, though.

“The throng of dignitaries had us trapped,” Barnum said. “We couldn’t move.”

Barnum said that was the first time he allowed himself to think of the magnitude of his situation. He was 24 years old, on the world’s stage.

A few months later, George “Bud” Barnum received the Army Commendation Medal for meritorious achievement.

“Yeoman Barnum performed with dignity and impeccable military precision,” the citation reads. “Yeoman Barnum’s distinguished performance of duty throughout this solemn occasion reflects the utmost credit upon himself, the United States Coast Guard, and the military service.”

Barnum was told he was the only active duty member of the Coast Guard to have such a medal from the U.S. Army.