Some camps are even popping up deep in the woods of unincorporated Clark County

CLARK COUNTY — The issue of homelessness is no longer for cities alone. Increasingly, homeless camps are popping up outside of Vancouver, sometimes off the grid in unincorporated Clark County.

The shift comes even as the city and county struggle to find their equilibrium. Over the past few years the cost of housing in Clark County, and especially in Vancouver, has risen dramatically. While new developments may level things off over the next year or two, many people have found themselves priced out of the housing market. Even finding some place affordable to rent has become increasingly difficult.

Kate Budd is executive director for Clark County Council for the Homeless. “There’s a great study through the Journal of Urban and Public Affairs that says for every 100 dollars that rent increases, if you’re in an urban area the number of people who are homeless increases by six percent,’’ she says. “Whereas if you’re in a rural area it increases by 32 percent.”

As rents and home prices jumped in downtown Vancouver, many people moved out into places like Camas, Washougal, Battle Ground, Woodland, and La Center. But that has driven prices up in those areas as well, meaning North and East Clark County are now experiencing an increasing rate of homelessness. While many of those people will move closer to resources, others want to stay close to places they’re familiar with. That has led to a rise in homeless camps along freeways, and vacant lots around the county.

“We’re seeing more people camping in the woods and very rural areas,” says Budd. “We’re also seeing more people that are just on the side of the road in campers, or sleeping in cars. We’ve actually now had to incorporate the Gee Creek rest stop up north because there’s such a high number of people that are without homes circling a few rest stops as they try to find something more stable.”

You’ll also find a revolving door of homeless families living semi-permanently at places like Paradise Point State Park. They can camp there for up to 30 days in the off-season, before needing to leave for at least 72 hours before they can return. While some of that population actually lives a nomadic life by choice, many others are simply unable to find a permanent place to set down roots as they try to get back on their feet.

Perhaps more concerning, there’s also been an increase in the number of people living semi-permanently way off the beaten path, either in non-permit camping areas, or even deeper in the woods.

“What we find is that they are essentially survivalists,” says Budd, “that they are incredibly skilled, honestly, and able to meet their basic needs while living out there and trying to find a job and save enough money to get back into housing.”

Patrol Commander Phillip Sample with the Clark County Sheriff’s Office says the homeless situation outside of Vancouver has been an issue for a while.

“It comes and goes in waves,” he says, “and I do think that people will travel, because it seems like when the city will have some type of emphasis going on where they’re pushing people out of the privately owned properties, they just kind of look to the county. Then we start getting calls from our citizens complaining. And there’s really not a whole lot of places we can offer them to go.”

Bettina Boles supervises the Yellow Brick Road outreach program with Janus Youth Services, which has volunteers who go out to reach the homeless wherever they are. She says the homeless tend to be more visible at certain times of the year.

“People will travel up to Seattle during the Summer, and then they’ll travel down to the Bay Area and further during the Winter,” she says, “and Portland and Vancouver are kind of right in the middle of that. So the traffic kind of ebbs and flows along I-205 and I-5.”

Boles says camps are often more of a staging area, and some of the homeless community are moving out to the country for the same reason others have: less crime, and less chance of their stuff being stolen.

For law enforcement, the situation with homeless camps is a bit like playing whack-a-mole. As one homeless camp is disbursed, people simply move elsewhere. If they get chased away from there, they usually just move back into town or elsewhere in the county. With resources limited, the Sheriff’s Office can only respond to complaints, so many campers can escape notice if they keep a low profile, especially the further off the grid they are. And even if they do get in trouble, they’re not likely to spend a lot of time in jail unless it’s a serious crime.

The causes of homelessness

The image of the “average’’ homeless person is branded into most of our minds. While they are generally the most visible example of homelessness we see, all of the groups we spoke with agreed that mental illness, drugs, alcohol, and a history of crime are not the major factors contributing to homelessness. They get the headlines, and potentially require the most resources to deal with, but the majority of people currently without a place to stay simply can’t scrape together the resources to get back into housing with the markets the way they are currently.

In fact, Budd says, the most common problem they see is not people who can’t afford the month-to-month expense of an apartment, but that fewer people can afford the high cost of getting into a place. The average move-in cost is currently $3,000. Numerous studies have shown the number of people with that kind of emergency savings continues to dwindle.

The Council for the Homeless has been pushing for legal changes they believe would help, such as allowing residential developments in commercially zoned areas, as long as the builder commits a percentage of the units to affordable housing. They also recommend increasing the amount of warning landlords need to give a tenant before raising their rent, or evicting them without cause to at least 90 days.

The state legislature did pass new rules this year aimed at preventing discrimination against renters who have a Section 8 voucher. Vancouver has enacted similar rules, but Mayor Anne McEnerny-Ogle says there’s no interest at this time in pursuing rules like Portland did, in which landlords can sometimes be required to pay all or part of a tenant’s moving expenses.

Kate Budd knows that there’s a fine line when you start talking about rules for landlords, because property owners are facing their own upward pressure when it comes to costs. Many saw their property taxes climb by 10 percent or more just since last year. Some, much more than that. Still, she says landlords who work with them to help people get into a place often find out it’s a win-win situation.

“The reality is that the majority of the time things work out very well for the landlord,” she says, “because they’re getting their money. And for the tenant, because they have a home.”

One of the programs the Council has is working with people to help them better organize their finances, so they can be sure to pay their rent on time, and teaching people how to be a better tenant, so that a landlord can’t find reason to evict them.

Frustrated homeowners

As the homeless population spreads further out, the Sheriff’s Office is dealing with a rising number of complaints from property owners. Sample says one current example is near the Goodwill store on 78th Street in Hazel Dell. A wooded area to the north, in-between two fairly new developments, has seen a number of transients move through.

“That one section in the middle is owned by like three or four different people,” says Sample, “so trying to actually find the property owners to say ‘hey, are you allowing these squatters to be on your property, or do you want them off?’ because the community around them are getting fed up with people coming in and out in the middle of the night, walking through their property to get to other places, going through their trash bins. There’s been property damage, there’s been arguments, almost some assaults happening.”

In fairness, he adds, a number of homeless camps do seem to do a better job of self-policing, and they get few complaints about them. In general, the sheriff’s office takes a soft-handed approach, reacting to situations that arise, rather than proactively seeking out homeless encampments.

Right now the biggest aggravation, for homeowners and law enforcement alike, are derelict RVs. Often times they’re parked either on vacant lots, or along neighborhood streets. And getting rid of them can be a pain.

“The challenge for those is that the towing companies aren’t taking them like they used to,” says Sample. “There’s a disposal fee associated with it, because of environmental issues. You know, black water, freon… these RVs have to be parted out in order to be taken. A lot of times the disposal amount is more than the vehicle is actually worth.”

Homelessness by the numbers

Last year, The Council for the Homeless received requests for emergency shelter from 577 families and 1,500 households without children. They were able to find shelter for about 4-in-10 of those. They also had requests for housing assistance from 743 families with children, and 1,716 households without children. Of those, only 10 percent were able to get assistance.

Outside of downtown Vancouver, homelessness is rising, but not as steeply. While the numbers of people listing their last permanent address as Battle Ground, La Center, Ridgefield, etc. is increasing, many of those people end up closer to where resources are available.

Perhaps more concerning are the numbers of students in local schools who either are homeless, or in transition from one living situation to another. Last year, Battle Ground schools had 63 students listed as homeless and unaccompanied, with another 305 in transition. Living in a car, or on someone’s couch, it turns out, makes getting homework done a far more difficult task. The uncertain living situation can contribute to poor learning performance, making success later in life harder to achieve. Finding a way to break that cycle, many believe, is a major key to stemming the homelessness situation in the future.

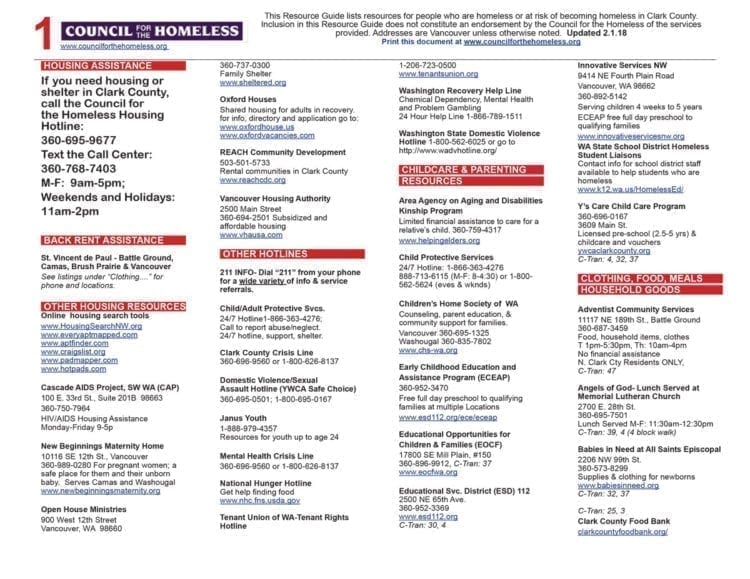

In some cases people don’t realize what programs might be available to help them get back on their feet. In other cases, they simply don’t care. For the most part it’s up to the person in need of help to decide whether they’ll seek it out. But the more spread out they are, the harder it is for them to access those programs, or for volunteers to reach them.

History of Homelessness

A quick check of the Clark County webpage will turn up a 10-year plan to deal with homelessness, enacted in 2005. The recession changed some of those plans, as unemployment spiked to over 15 percent in 2009. But the recovery has brought its own set of problems, as job growth has created an influx of new residents seeking the rural lifestyle of Clark County, with easy access to Portland. With rental rates and home prices far outpacing wage growth, an increasing number of people have found themselves on the outside looking in at the American Dream.

As for when things will improve, the experts say there’s a lot of catching up to do: Home construction needs to catch up with demand, to reintroduce competition into the rental market. Wage growth needs to catch up with the cost of living. Mental health and addiction treatment services need to catch up with demand.

If you talk with a dozen different experts on homelessness, you’ll likely hear at least a dozen different possible solutions. It’s a problem whose solution has escaped some of the most brilliant minds in government and the private sector. It’s an issue of economic factors, human fallibility and gullibility, and social prejudices colliding. For some homelessness is a temporary pothole on the road back to normalcy. For some it’s a vicious cycle that seems impossible to break. For others homelessness is freedom, and way of living they’ve chosen. Separating those people out, and finding a solution for all of them is a difficult task in the best of times. It’s sort of like putting together a 5,000 piece puzzle by committee, only the picture changes every few years.

Also read:

Vancouver gets $300,000 donation for new homeless day center