Student advisor feels older students have been neglected

The Hockinson School Board met this week in their second special meeting. Following last week’s meeting, where the board members pushed for a faster reopening timeline, Superintendent Steve Marshall offered new options for the board to consider –.specifically reopening plans for secondary schools.

Marshall noted that the norm for the past nine months has been to have three or four school board meetings per month, often lasting three and occasionally four hours. He applauded the commitment and leadership of the board in representing the students, families and staff of the Hockinson School District.

“This reopening campaign is a K-12 campaign,” Marshall said. “It touches on every staff member positively and negatively, and everywhere in between. Ultimately, we hope that it benefits our students. They’re the reason we exist, to serve our students. Teaching and learning has to have a consumer and the 1,700-plus students we have are the reason we’re here.”

Board member Greg Gospe reminded all the families watching that because it was a special meeting Monday, and with the agenda set, he didn’t expect any specific decision to be made. A vote would occur at a future date.

Under citizen comments, parent AJ McKay praised board member Tim Hawkins for his leadership and remarks at the previous week’s special meeting. But he went on to say that last week’s proposal should have been done perhaps at the beginning of the school year. “It was way too little, way too late.”

“You guys have buildings sitting empty,” McKay said. “You haven’t gotten even partial classes into them. Why can’t you have freshmen in there? Why can’t you have the younger grades in the younger schools? That makes zero sense to any of us. Why not have anything that can put those buildings to use, that can put kids in seats with teachers?”

Caution and scientific approach

Parent Ryan Kramer expressed a different sentiment. He appreciates the caution and the scientific approach to reopening. “We are in a pandemic, it is incredibly serious,” he said.

Kramer expressed concern for the teachers. He also mentioned a survey of first and second graders, where 75 percent were interested in coming back. “If you have 75 percent coming back, how are you going to limit class sizes? How are you going to implement social distancing? How are you going to keep someone that is infected from infecting all the other kids and from infecting my kids?”

Providing information related to Kramer’s questions was at the heart of the school board’s deliberations. The meeting lasted three hours, and went into some very detailed discussions regarding the options to be considered.

Marshall responded that there have been four different surveys taken since last summer. There has been a consistent result where 75 percent of parents want to see some kind of limited, in-person education.

Gospe spoke to the increased interest in school board meetings. He mentioned there were almost 100 people online, viewing the meeting. Before the pandemic, they would have three or four people at a meeting. “I think that there is far greater visibility into what we do” with the online meetings.

In addressing various options of choice, Marshall said they were exploring three options for some students. “We’re able to move forward offering Hockinson Virtual Academy (HVA) as option one, remote learning is option two, and option three would be in-person learning.”

At the secondary level, he anticipates two options — remote HVA and in-person. “The matrix of a six-period day and certifications among teachers makes it too challenging to create that third option of remote,” he said.

Kim Abegglen is an associate principal at Hockinson Middle School. She gave a very thorough presentation on what in-person education involves in terms of ensuring staff and students safety.

Abegglen emphasized that their short-term focus is ensuring the health and safety of students, staff, and families. She also mentioned continuity of learning. “In the long game, we are striving for that academic success for all of our Hockinson students.”

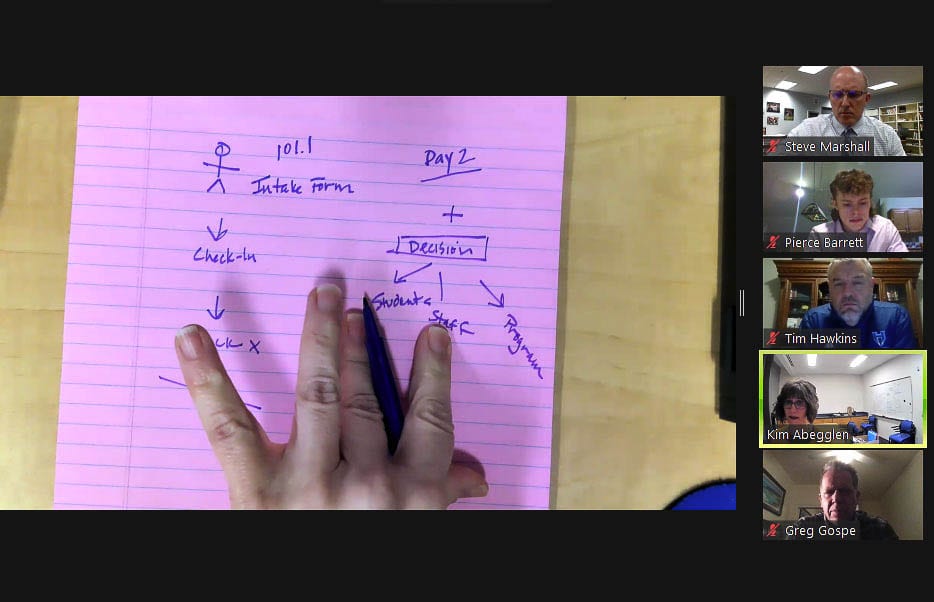

Abegglen highlighted a real world scenario, where one student told their teacher they were experiencing chills. The student’s temperature had been taken as they entered the school and was normal. But with the student isolated, their temperature was 101.1, which triggered a whole series of procedures and protocols.

Abegglen laid out an extensive flowchart, all part of a decision matrix the staff had created.

The parents consulted their healthcare provider and ultimately had a COVID test administered. The student tested positive. This then triggered additional actions by the school staff. Ultimately, multiple staff members and two small pods of students had to be quarantined for safety reasons. Because of the lack of staff, school was forced to close down.

Abegglen addressed scaling up, and bringing more students back to the classroom. “Our goal is always to do so in a manner that minimizes exposures and maximizes that continuous learning,” she said.

“Being able to staff our programs, to work through quarantines” is part of drafting options, said Abegglen. “We have to look at the way we structure; what does that mean if some pod is quarantined? What can still continue and how do we maximize that?”.

Marshall mentioned that Abegglen had been quarantined twice, and was out of the school building for a total of four weeks.

Brian Lehner, middle school principal, laid out the two options for resuming secondary education in person and how they might phase them into action. He referenced the new guidance from the state about how many kids we can have in a classroom. “We had been working under the model of five kids and two adults in a room as small groups.”

“We have not had a transmission in school,” Lehner said and “that’s been good.” He said a few cases of the virus have come from outside the school. “When it got inside, we didn’t spread it.” Lehner noted there has been a small number of children with limited interaction between the students.

Social, emotional and support model

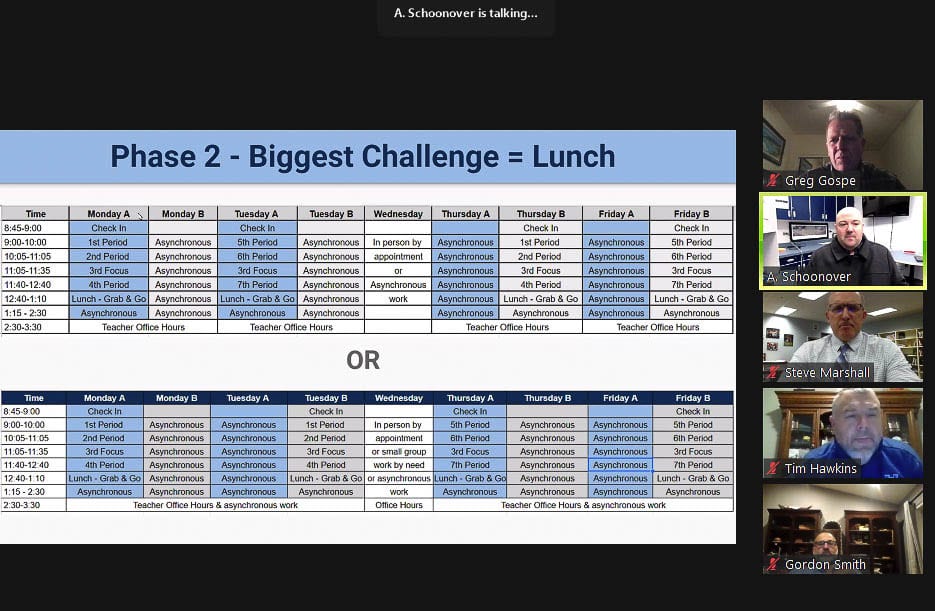

The first option was more of a social, emotional and support model. Mondays would offer periods one through three at the middle school. On Tuesdays, periods four, five and six. Students would work offline or online at home without a teacher on Wednesdays. However teachers would be available for students to contact for help. On Thursday and Friday, they would repeat the Monday, Tuesday sequence.

The plan is based on a maximum of 15 students and one teacher in a classroom, per state guidance. “To do that we can’t have all of our kids in a class in our schedule come back at the same time,” he said. They created cohort A and B. About half the students study at home and half are in the classroom at the middle school. They reverse the next day.

In designing the options, they decided that all lunches would be at home. “One of the concerns with lunchtime is putting a large number of kids without a mask in a space and then the contact tracing that will go from that if something happens,” Lehner explained.

Lehner also mentioned that this model would allow them to use high risk staff, teaching the online classes.

The next step would happen after they do an option where kids aren’t switching rooms. A significant difference between elementary and secondary school is keeping kids in one location. In elementary schools, the kids stay in one location with one teacher. Using the cohorting model at a secondary school, would you keep kids in one room and then maybe switch teachers around to those rooms, he asked. It could limit the number of electives and create other challenges for secondary school students.

“Rotating periods is still very concerning to be the starting point for us, if we’re going to do this and have kids rotate and right off the bat,” Lehner said. “This would not be our selection for first choice if we’re going to do the phasing in like the guidance says.”

Lehner suggested this could be part of a phased-in approach, “after the first step, if our numbers stay below what the guides say,” he said. “And then we can bring larger amounts of kids back.”

“What does that look like when the kids are transitioning between classrooms,” he asked. That potential of too many contacts and spreading the virus is their concern. Classrooms would also have to be disinfected everytime the kids change classes.

Lehner mentioned one model for at-risk kids, using a sixth grade cohort, A and B plan. They would bring in 15 students per room on one day and have two rooms with an opening wall between them. The two rooms would have 15 children each, and then either two or three teachers can be in class, going back and forth between the rooms.

Based on what students need, it provides an opportunity to have multiple subject matter teachers in a class instead of just one teacher, according to Lehner. This model would be for those students who are struggling. They could serve 30 children in each grade level. “So 90 kids on Monday and a different 90 kids on Tuesdays,” Lehner said. “That would get 180 out of 360 remote learning kids back into school.”

Confidence moving forward

Board member Tim Hawkins took the lead in responding to the presentations. He praised the attention to detail and how much rigor was put into the process. “It makes me feel much better about even moving ahead, as it relates to our staff and our students.”

“That’s far more detail than I expected to get,” he said. “I really appreciate how deep you went, because it made it very clear how serious you are taking this and how it’s possible,” in reference to Abegglen’s presentation. He emphasized that it’s not easy, but possible to move forward.

Hawkins noted that in the three different scenarios, the 15-person limit (by the governor) is the biggest barrier.

Hawkins shared that he had spent a lot of time thinking about the process. “There are some schools that have gone back and are offering both in person and remote at the same time.” He suggested teachers should switch their teaching bias towards the camera, towards the remote students instead of the kids in the classroom.

“The people in the room are benefiting from what you’re teaching remotely,” Hawkins said. “That’s where the biggest success has come from,” referencing schools already doing in-person instruction combined with remote learning. “I know it’s a script flip in terms of how those normally work. I’ve seen that work well.”

Marshall reinforced the point Hawkins made about changing the mindset of the teacher. “My wife, who’s an educator, said the way they’re doing it at her school is ‘I teach to the camera.’”

Hawkins asked Lehner which of the various options he preferred. Option one is Lehner’s preference because it has the most teachers involved. “It would have all teachers pretty much doing the same type of thing,” he said. “And it gets all kids here over two days.”

Hawkins asked: “if option one goes well, can you scale that faster? Our goal is full (in-school) learning.” He noted the other options had scaling directions.

The response was “that depends,” referencing many different factors including lunches at school or not, and how to combine asynchronous learning with in-classroom learning. Lehner also mentioned the challenges “if” they allowed kids to switch classes as a variable.

Focus on struggling students

When it came to high school options, Marshall spoke about trying to focus first on the students who are failing. He indicated that about 15 percent of the students are really struggling. “Our biggest concern right now is the amount of kids with multiple F’s.” He wants the first phase to be an intervention focused, targeting of students.

“Math is our most difficult subject every year,” said high school Principal Andy Schoonover. He suggested focus days for each subject for the troubled kids.

Moving to the rest of the high school students, all the options were tied to the 15-person limit from the governor. They proposed half-day instruction in the classroom. One was half the students on a morning schedule and the other half there in the afternoons, four days a week with Wednesday’s off.

A different option was two cohorts where half attended Monday and Tuesday, and the other cohort attended Thursday and Friday. In both options, all remaining instruction would be asynchronous learning at home.

The Mead School district in Spokane was discussed. That district offers students the choice to learn from home or in the classroom. They have students changing classrooms and eating lunch at school. That is a significant contrast from what was proposed by Marshall and his staff, who want to phase into classrooms, but not deal with lunch at school issues.

Pearce Barrett is a junior at Hockinson high school and a student representative on the school board. “I think our school has done amazing with the situation we’ve been given, but the district is between a rock and a hard place.”

“As a high school student, I have felt the struggle of the SAT is pressuring me,” he said. “I’ve got to take that at some point, and online learning just is not the same as in class learning.”

“As an older student, I think there’s a feeling of neglect, versus the first and second grade,” he said. “First and second graders should be going back. But we focus a lot on the earlier grades, rather than the older students. High school is just a crucial time. I don’t remember first grade, but I definitely will remember my junior year, my senior year.”

Barrett feels that attending school in the classroom should be viewed as a privilege, not a right.

“If kids don’t want to wear the mask, they shouldn’t be putting other kids in danger,” he said. “They can learn from home.”

“The reason that we’re in school is to teach, it’s to learn, and it’s not to appease the district or the state.” Barrett concluded by encouraging the school board and administration to “push as far forward as we can” to get kids back into classrooms. “I’ve seen a lot of friends in other states who have gone back to school,” he said. “It just feels like I’m missing out.”

Near the end of the meeting, Superintendent Marshall shared he thought they could compress some of the intervention work for the transition grades of six, nine and 12. But he indicated a desire to continue to listen to guidance from Clark County Public Health. “They have given us good guidance. We want to stick really close to that threshold at the elementary school, which is 350 per 100,000 and 200 per 100,000 for high school.”

Hawkins continued to push. “I think we need to win. I think we need to find a way to see (grades) nine through 12 back in school. If we stay at this pace, those kids won’t see school this year. And I think that that’s a tough run for our kids. I really feel like we owe those high school kids more.”

No formal decision was made. The school board will meet in its third special meeting on Friday, where they hope to take formal action on a plan to accelerate the return to in-classroom instruction for all students.