Project would progress in phases; pilot program first; Vancouver stop in phase two

VANCOUVER — Many decisions must still be made and many hurdles must still be jumped, but the Friends of Frog Ferry (FFF) received the results they have been hoping for since 2017: a passenger ferry service is feasible according to a study concluded this month.

The group’s third and final commissioned feasibility study offered optimistic results for the future of a service connecting Vancouver, Portland and possibly Oregon City, via water.

In a virtual press conference on Oct. 20, group founder Susan Bladholm, along with John Sainsbury of Maritime Consulting Partners, LLC relayed the results of the final stage of research on operation.

“Ultimately, the biggest goal and outcome for this project is really connecting people to their rivers,” Bladholm said. “For the Portland area, even though we were founded here over 200 years ago … we often view our riverway as an impediment. It’s something to get over. It’s partially why we’re the city of bridges. We want to reconnect people with a river and foster a greater sense of stewardship and reverence for the river.”

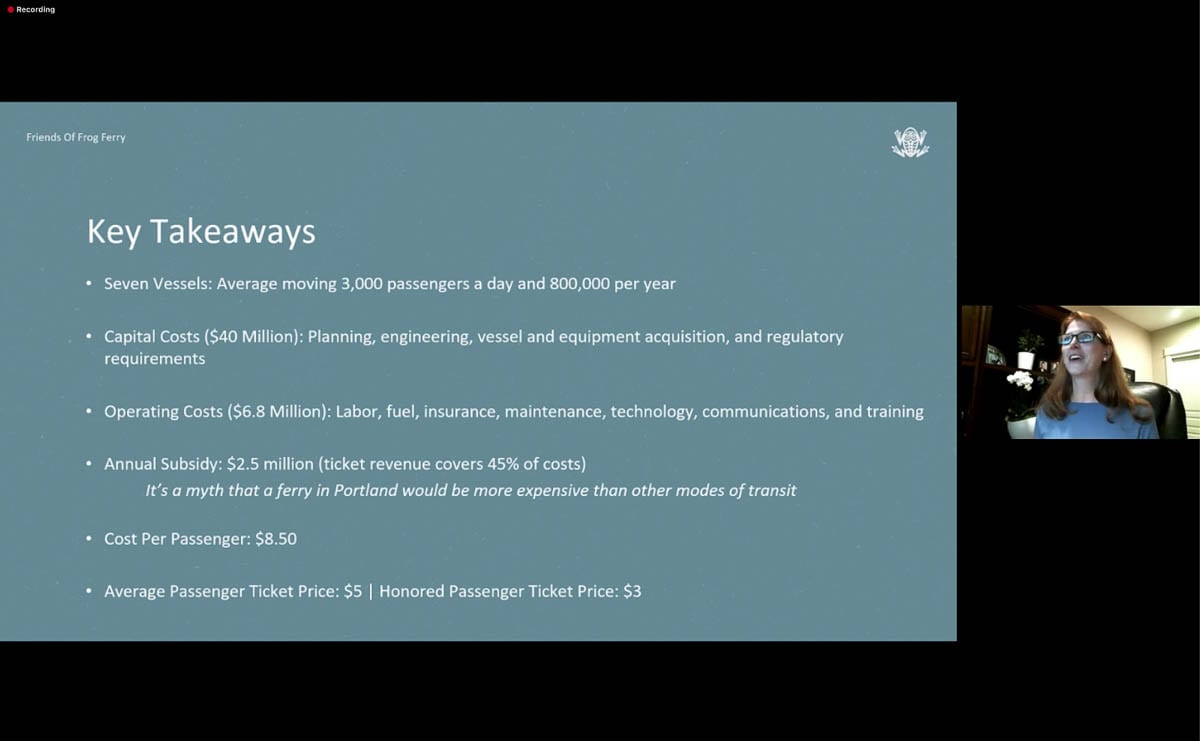

The key takeaways from the final study focus on three main areas of feasibility: the vessels and rivers, the routes and the costs.

After surveying portions of the Columbia and Willamette rivers and assessing bridge obstacles, river debris levels and other factors like weather and currents, Sainsbury and his team suggested a fleet of seven vessels with two ferry designs. In order to mitigate the bridges and debris, the vessels would be designed with single decks and specialized hulls.

The main routes are split into two sections; the upper and lower river. The lower section would include the Columbia, lower Willamette and Vancouver, and would allow for 90-foot vessels with a capacity of 100 passengers. The upper section would be part of the more crowded Willamette, and would use more maneuverable 60-foot ferries carrying 70 passengers.

“Some of the key elements are very different on those two sections of the rivers,” Sainsbury said. “That’s very important because it led our team in a different direction, and really trying to address the challenges that were posed by both of those different sections of the river and take advantage of the opportunities that they also provided.”

Sainsbury explained that while using all suggested stops along both rivers with the seven vessels, which are still slated to be hybrids, the service could carry as many as 3,000 passengers per day and close to 800,000 a year.

The route most interesting to Clark County residents is likely the that from Vancouver to Cathedral Park and then Salmon Street in downtown Portland. After the study and with the suggested vessels, it was found that a direct route from Vancouver to Salmon Street would take 44 minutes, and the same route with a Cathedral Park stop would be close to 55 minutes.

“The other objective was headways, which essentially is the amount of time that elapses between a departure from any given point,” Sainsbury said. “We wanted to make sure that those headways did not exceed 30 minutes, which is pretty important for commuters who are trying to plan their commute, where they need to link to other transit modes.”

The study found the total cost in capital expenditures, or CAPEX, would be $40 million, with the potential for 80-20 percent federal to state match if the group secures a public entity partner. Average yearly operating cost is estimated at $6.8 million with a $2.5 million subsidy.

Bladholm said that while many people have told her they believe a ferry service would be just as, if not more expensive than other modes of public transit like trains or buses, this is largely a myth, according to comparisons with TriMet and Portland Streetcar.

With ticket sales expected to cover 45 percent of costs, the cost per passenger would be $8.50. The ticket price for a normal customer remains at the previously estimated $5, with tickets for honored passengers, like veterans and seniors, being $3.

“It sounds like a lot of money to taxpayers like you and me,” Bladholm said. “But for a transportation mode, it’s a very, very small amount in relation to other modes of transit and the amount of money that we spend in our region every year for transportation, and we believe we need a variety of modes of transportation.”

FFF is now mainly focused on finding a public entity sponsorship, and then hopes to launch into a pilot program in 2021. That program would run a single vessel from two route points, likely Cathedral Park to downtown Portland. The project would then enter phase one, with operation on a similar route. Phase two, would be where a larger expansion, including a Vancouver stop, would be added.

The group is aiming for a partial or full launch of the service in 2024. You can read the full feasibility report here, along with other resources about the proposed ferry service.