Cortright: ‘I have no idea where it is they think they’re going to get the money for this’

Yesterday, Clark County Today published a story where economist Joe Cortright said Oregon and Washington were not obligated to pay back $140 million to the federal government if the states don’t follow through with a project to replace the Interstate 5 Bridge. Cortright claims the states could simply choose the “no build” option that was included in the NEPA environmental process.

Cortright went on to discuss many additional aspects of regional transportation issues. These included the seismic issues, transportation funding, tolling, Departments of Transportation (DOT), shopping in Oregon, and more.

Clark County Today also asked Cortright what he believed was driving the revival of the Columbia River Crossing (CRC).

“DOT’s love to build things,” he said. “This is the next big thing that they want to build. It’s always been on their agenda. Very big bridges are the epitome of the highway building art. So it doesn’t doesn’t at all surprise me that they’re trying to revive it.”

He then touched on the funding issues. “The nut that they haven’t cracked and they refuse to own up to, is answering the question ‘how are you going to pay for this?’” asked Cortright. “Who is going to pay for this?”

The CRC became a $3.5 billion proposal. When Washington walked away, it got “slimmed down” to a bit below $3 billion as Oregon briefly considered going it alone. But today it’s got to be at least $4 billion according to Cortright.

“That’s a heavy lift,” he said. “There isn’t $3 or $4 billion sitting around in either state’s transportation budget. In fact ODOT is already saying that due to the reduction of driving for COVID, they don’t have enough money to maintain existing roads.”

Gas tax revenues are in decline for both states.

“Where does this money come from,” he asked. “I think they’ve been a little bit more forthcoming this time and saying that we don’t get this without tolling. But you know, that’s what sank the project before. They never addressed tolling honestly.”

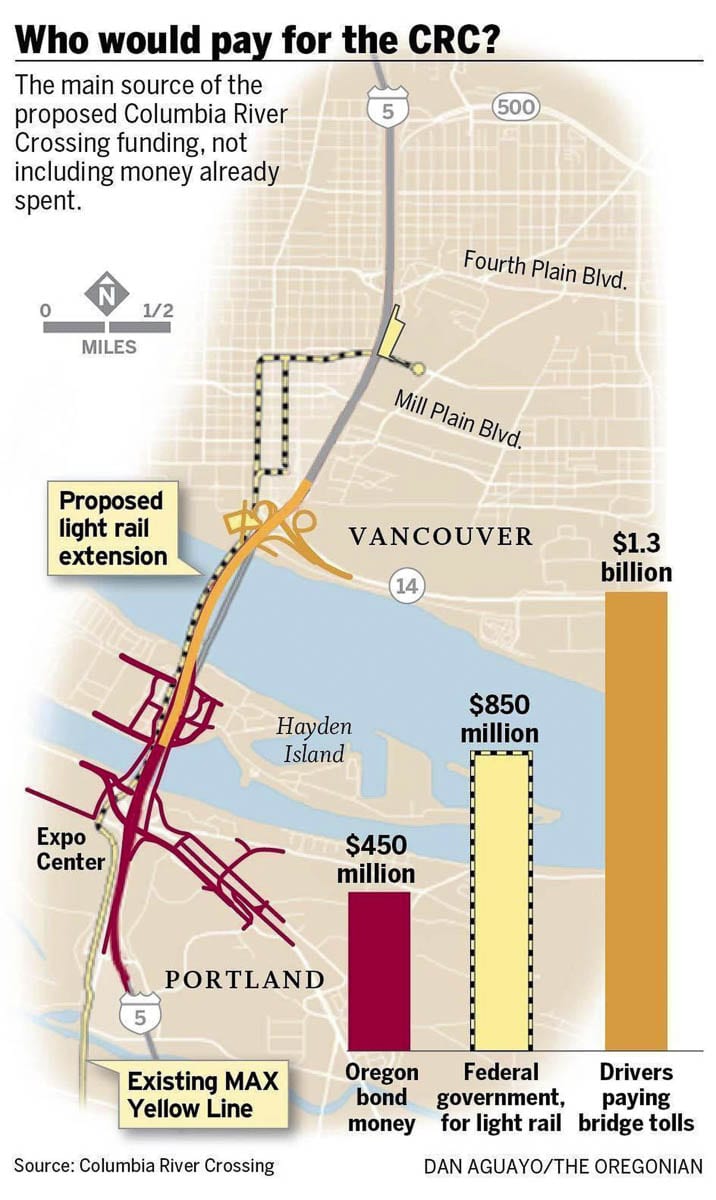

Cortright said about one third of the price of the CRC funding came from tolling. He said peak hour tolls for cars would be $3.60 cents each way, citing ODOT and their CDM Smith study. Others, including former Vancouver Mayor Tim Leavitt claimed they would be $8.

Cortright mentioned ODOT’s claim that the tolls would cause about half the vehicles to divert to I-205, because in the CRC, they planned to charge tolls only on I-5.

“They wanted to build a 12-lane bridge (6 in each direction), spent $3 Billion, and chased half the vehicles away, creating gridlock on I-205,” he said. “That was obvious to anyone who looked at the project in 2007 or 2008. And yet they waited five years to sort of deliver the truth.”

Cortright believes transportation officials need to address funding issues up front, before they get to a specific project.

“I think you have to start with that and say, if you want a new bridge somebody has got to pay for it. The people who use it are going to have to pay for at least a portion of it. Given the price that we would charge, would enough people use it to justify building it?’’

“I think the strategy of the DOT on both this project and the (I-5) Rose Quarter, is to say well, we’ll build it first and then we’ll talk about tolls,” Cortright said. “As an economist, that was just nutty.”

He addressed the question of how many lanes are needed across the river.

“You need a very different number of lanes depending on whether you charge a toll or not,” he said. “If you charge a toll (right now) you probably have plenty of freeway capacity across the river, especially if it varies by time of day.”

Cortright supports “time of day tolling” where you move vehicles away from the peak hours. He believes there are a lot of people who have enough flexibility to travel at different times.

“For those who must make a trip at a certain time, they pay three and a half dollars at the peak and $1 or nothing at the off peak,” he said. “I think what tolling does is it allows people who have put a high value on their time to purchase a fast and reliable travel time. That is something you don’t have the option to buy now.“

One of the challenges of tolling is that it causes traffic diversion, as people seek to avoid paying the tolls. ODOT shared in their Value Pricing PAC meetings, 80,000 vehicles are presently diverting onto side roads. They expect an additional 50,000 vehicles to divert onto side roads when both I-5 and I-205 are tolled.

Cortright believes we people need to be encouraged to make their trips at different times, when the roads are less congested.

“An interesting thing about the dynamics of traffic is you don’t have to get a whole lot of cars off the road to get much better service,” he said. “If we were to reduce traffic volumes at the peak hour by about 10 to 15 percent, we get free flow speeds.”

Some people will challenge that by pointing out significant parts of I-5 are congested nearly half the day. People are already adjusting their travel times, and yet roads remain congested. In 2017 ODOT reported “traffic congestion in the Portland region can now occur at any hour of the day, including holidays and weekends,” the report said. “It is no longer only a weekday peak hour problem.”

“There’s a lot of science on this but it basically says you maximize the capacity of a roadway at about 45 miles an hour,” Cortright said. “That’s because you get closer following distances and you get a steady flow of traffic. That’s what we should be doing. Everybody would be better off if we could reduce traffic just enough to keep the roads moving at that speed.”

Cortright said “our road system is a multi billion dollar asset. It’s an incredibly expensive investment that we’ve made, and we do nothing to manage it.” He believes that “congestion pricing” tolling will cause Clark County people who shop in Oregon to either adjust the times they shop in Oregon, or perhaps just do their shopping in Washington.

“We know Clark County residents save $150 million a year in state sales tax by shopping in Oregon,” he said. “In big round numbers, the shopping traffic across the river is 10 to 15 percent of all that traffic. Essentially, you’re saving about eight to nine cents on the dollar if you buy your taxable goods in Oregon.

“The great thing about a lot of those trips, not all of them, is you get the same tax break whether you shop at the off peak hour or the peak hour,” he said. “We can encourage a lot of people to make those shopping trips at other times.”

Cortright was asked why would the DOT’s be focused on building this bridge at this location, as opposed to building another bridge at another place? Or why not refurbish the existing bridge and build what former state Rep. Liz Pike called a flyover, which was kind of like an express lane?

“I’d be doing a lot more speculating to try and answer that question,” he said. “I always describe the CRC as not a bridge, but a five mile long 12-lane I-5 freeway that just happens to cross a river.” They wanted to build a big project, but just in that area two miles either side of the river.

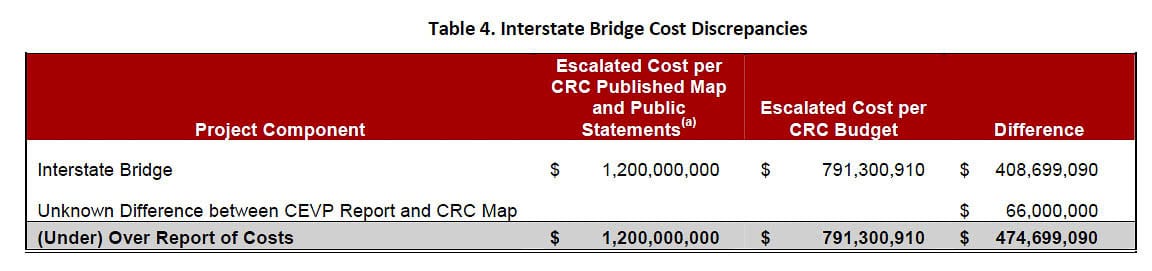

“If it were just replacing the bridge, it would be less than half the cost,” he said. Forensic accountant Tiffany Couch revealed that CRC data indicated the cost of the bridge was $792 million.

Many people are genuinely concerned about the seismic safety issue, which politicians and the DOT’s regularly mention. One of the two Interstate Bridge structures was built in 1957 and the original bridge was upgraded at the same time.

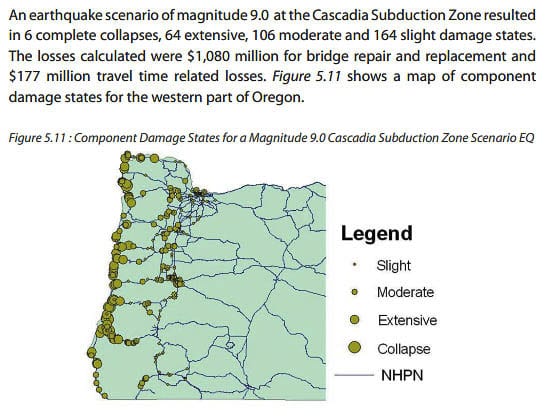

“How do we respond to a likely or possible Cascadia subduction event,” he asked. “I think that’s something we need to be concerned about; not just for this bridge but for the whole region’s infrastructure, which we don’t think about much.”

He noted the Marquam Bridge on I-5 as it crosses the Willamette River has significant seismic problems as well.

“The Marquam is highly vulnerable,” he said. “We need to think about it in two ways. We need to be thinking about how do we have a minimum survivable system? How do we restore a network quickly?”

“It doesn’t mean you fortify every bridge. We need to have at least one bridge across the Columbia River. We need to have at least a couple of bridges across the Willamette including south of Portland. We need to have connections to the coast. I don’t think we’ve thought about it that way.”

“I think they’ve (politicians and DOT’s) sort of triangulated between all of the different political forces and figured this in their own interests, and that’s what they’ve come up with,” he said.

The I-205 Glenn Jackson Bridge was built in 1982 and is the northwest’s newest bridge across the Columbia River.

Today, the Oregon DOT released their supplemental draft EIS statement for replacing the Hood River bridge across the Columbia River, roughly 60 miles to the east of the Portland metro area. “The bridge would be designed to be seismically sound under a 1,000-year event and operational under a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake” states the EIS. “The total Project construction cost is estimated to be $300 million in 2019 dollars.”

Cortright said we should focus on the BNSF rail bridge. He pointed out it’s not only older, but rail would bring the greatest amount of relief supplies to the region if there were a major disaster like the much mentioned Cascadia 9.0 earthquake.

“But the real question is not, can we predict perfectly what happens, but how do we respond the next day; you know 48 hours after we see what’s left and what fell down,” he said. “How do we invest to get that minimum system up? It’s a lot more important to be able to figure out how you restore and respond than it is to sort of bulletproof any one particular bit of infrastructure.”

If the major disaster were to happen, “you probably don’t want to rebuild exactly the system we have today,” he said. “There’s no necessary reason why we would want to have exactly the same transportation system. We want to have some different priorities.”

The conversation closed out, once again referencing the funding. On Dec. 1 the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project team will release their funding proposal. “I’m eagerly awaiting their financial plan, because I have no idea where it is they think they’re going to get the money for this,” he said.

Cortright believes we should toll both the I-5 and I-205 and dedicate that money to maintaining them, first and foremost. “A relatively high priority is either repairing if it’s possible, or replacing those two bridges,” he said. “So toll first and then build later.”

Regarding the bridges — “if they’re fixable fix them. That’s a short term solution, do it short term. But once you do the tolling then you’ll have the answer to that question of how many people really want to go across the river and how big a freeway do we need. And oh by the way, how much money do we have to pay for it.”