One analyst believes the move could represent a cost savings for the county

CLARK COUNTY — There is no question that equipping law enforcement officers or their patrol vehicles with cameras would be incredibly expensive. But research done at the request of the Clark County Sheriff’s Office shows that there may be tangible benefits that outweigh the initial cost.

Sheriff Chuck Atkins said the department was able to make use of an intern program to put together the report.

“I’ll be honest with you,” Atkins told Clark County councilors at a recent work session, “I have no problem with body worn camera programs myself, but it isn’t high on my priority of budget items. This is driven by our desire to pre-plan, get this information on the radar screen. Because, you know, we could have a big incident tomorrow [and] our community does want to drive body worn cameras immediately, or our state legislators decide that the state will have body worn cameras.”

The report was put together by Jean Dahlquist, a student at the Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University. She has dual master’s degree in Urban and Regional Planning and Real Estate, along with affordable housing law and policy.

“Before I was a master’s student, I spent six and a half years as a law enforcement officer in the United States Coast Guard, both on the ground and in the air,” said Dahlquist. “As a former law enforcement officer, it really grieves me to see the typical relationship between police officers and the public today. It was my hope that by doing this project over the summer, maybe I would come across some ways to build bridges, and to bring these communities back together.”

Dahlquist noted recent surveys have shown that nearly 90 percent of Americans support the use of body worn cameras for police officers, though just over half would be willing to pay increased personal taxes to fund them.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, nearly half of law enforcement agencies in the U.S. use body-worn cameras, and over 80 percent use some sort of recording device in their daily work. The Clark County Sheriff’s Office and Vancouver Police Department do not use any video recorders, either on officers or in patrol cars, though the sheriff’s office has had dash cameras in the past. Atkins said he wasn’t clear on why those cameras were removed.

Deputies face extreme workloads

According to the study put together by Dahlquist, the sheriff’s office has 80 patrol deputies, 70 of which are currently ready for work in the field. That amounts to 0.67 deputies per 1,000 residents. And overall staffing levels have remained largely unchanged since 1990, despite a 33 percent increase in the population of Clark County.

“The International City/County Management Association recommends that deputies are occupied with dispatch calls 60 percent of the time,” said Dahlquist. “When I went on ride alongs with Clark County Sheriff’s Office, it was my personal experience that deputies were occupied with dispatch calls close to 100 percent of the time.”

Dahlquist said one CCSO crime analyst said most deputies can’t even handle the dispatch call volume about half the time, meaning there is little to no time to monitor a traffic light, watch for drug deals, or simply patrol.

“This theme of overwork is carried out throughout the rest of the department. My favorite example is the poor Information Technology unit,” Dahlquist said. “They have work requests over two years old because they have not been able to get to them.”

The already high workload means added training could cause other systems to break down, said Dahlquist, making it difficult to implement new technology.

But the flipside, she noted, is that having video available can provide a useful tool when it comes to training.

Dahlquist said she encountered one such scenario while interviewing the police department in Parkland, Colorado as part of her report. They had used body-worn camera footage to help figure out how one officer ended up accidentally tasering her partner while attempting to arrest a suspect.

“They recreated this incident specifically for the deputy, and she was able to walk through, learn what she did wrong, and prove that she would respond better in the future,” said Dahlquist. “This is how a body worn camera program can turn everyday actions on patrol into a training tool.”

Cost versus benefit

The upfront cost of implementing a body-worn camera system can be eye-watering. For the technology, training, and video storage Dahlquist estimates one time costs could be anywhere from $224,398 to $337,708, with annual costs ranging from $174,188 to $276,128.

And that’s just for the technology.

The sheriff’s office would likely need to set aside another $300,000 per year for an additional sergeant, someone to deal with the technology, and one more public records employee.

One potential cost that can’t be mapped out is an increase in arrests and citations.

“Police officers and deputies, when they’re filming interactions, don’t feel like they can give people a pass quite as much,” said Dahlquist. “Someone’s on film breaking the law, deputies feel more obligated to make sure that they’re charged appropriately.”

But, she added, there are also quantifiable cost benefits to body worn cameras.

Use of force incidents tend to be reduced significantly when interactions are being filmed. Usually, Dahlquist stated, that’s because citizens being approached by law enforcement tend to be better behaved when they know they’re being recorded.

The presence of recording equipment also leads to a significant reduction in citizen complaints, all of which have to be fully investigated at great expense to the departments in terms of both time and money.

“If we look at similar departments, Las Vegas experienced a 66 percent reduction in citizen complaints due to their body worn cameras program,” noted Dahlquist. “Spokane experienced and even higher reduction of 78 percent.”

That reduction in use of force complaints, Dahlquist estimated, could save the sheriff’s office as much as $582,800 per year, along with an additional $62,000 savings in complaint processing time.

Cost savings that are potential, but difficult to calculate, include insurance rate reductions, a better chance of plea deals reducing court time, increased conviction rates in cases such as domestic violence and sexual assault, additional training opportunities, and even community relations.

“If a picture is worth a thousand words, what is a video worth?” asked Dahlquist. “Clark County Sheriff’s Office recently made a video of a deputy saving an owl. This video has been viewed over 67,000 times. And, actually, when I was looking for this video, I found it first in Chinese. It’s quite a hit over in China. So these videos can really have a big impact.”

The question of public records

Aside from initial and ongoing costs, the biggest question around body worn cameras and dash cams remains how to handle public records requests.

Dahlquist body worn camera programs in Seattle and Spokane initially had no cost for public records requests, but they quickly were inundated with requests for footage.

“These requests were not from concerned citizens wanting to know what was going on, they came from predominantly one or two requesters per department,” she said. “A local news agency tracked down one of these requesters and found out that the massive request was simply a form of police protest. They knew how expensive redaction was, and so they were performing these actions because they wanted to undermine the body worn cameras program.”

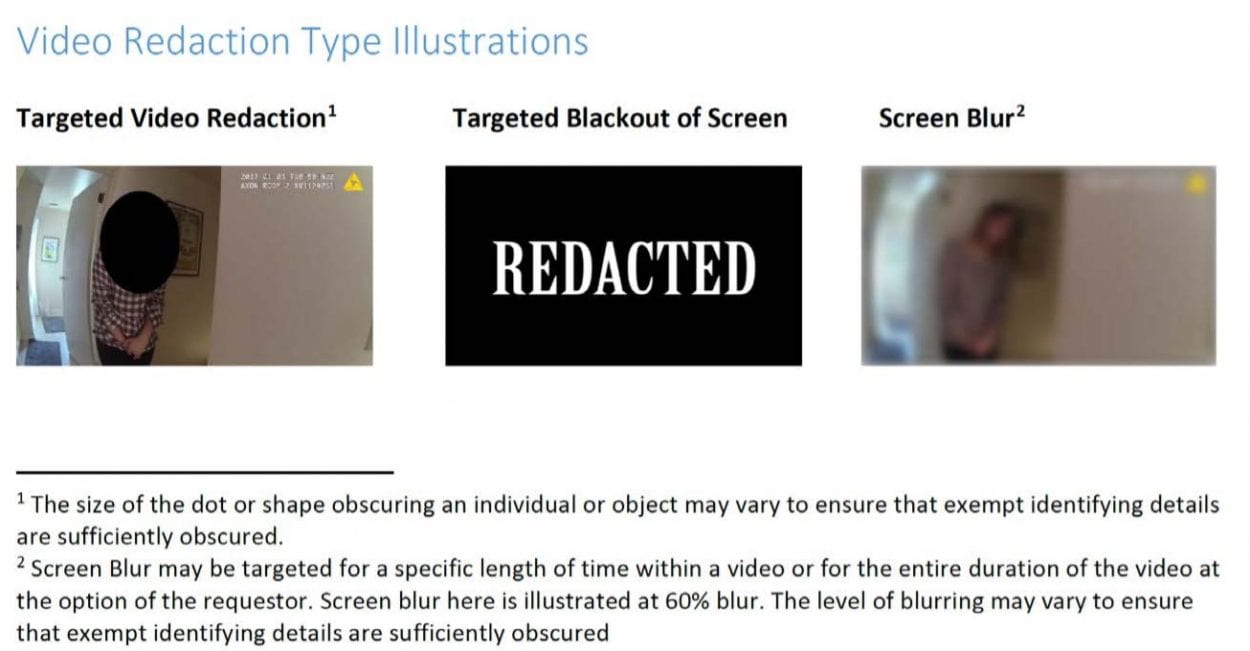

After that, Seattle and Spokane police departments implemented a tiered system to charge for video footage, based on the level of redaction and how many objects had to be blurred or covered.

Depending on what level of redaction is requested, Dahlquist said the sheriff’s office could potentially raise enough revenue to cover the cost of hiring an additional person to comb through footage for public record requests.

Sarah Leffler, public disclosure manager for the sheriff’s office, said state law does allow charging for video redaction, so long as the requestor is not directly tied to the case, or an attorney involved in the case. But there are still a number of gray areas about what can be redacted, which requires a manual review of each video, of which there can be many hours related to a specific case.

“There are some technological tools available that can help automate some of the redaction,” said Leffler, “but it certainly would be a time investment to maintain that program.”

The law mandates that any footage, even accidental recordings, be maintained for at least 60 days. Any video tied to an ongoing criminal case would need to be retained for the duration of the appeals process, which could be a number of years, depending on the charges.

The amount of storage is another potential added expense, though Dahlquist said their cost estimate had generally assumed a higher level of data storage.

What comes next

According to Atkins, the purpose of the study was simply to provide data to the County Council about the costs and benefits of body worn cameras, dash cameras, or audio recording devices.

After looking at Dahlquist’s report, Atkins said he believes that more is better when it comes to recording what law enforcement officers are doing on a daily basis.

“Because I’m a firm believer, from the data that I’ve been able to research, that more times than not — a very high percentage — the camera proves that law enforcement’s doing the right thing,” said Atkins. “And it’s quick to exonerate, and once that message gets out the false accusations are going to dump.”

Atkins called the work session a “continuing conversation” about the topic of police accountability and potential county investment in public safety. The county council will soon be taking up the issue of a new jail, which is likely to end up in a request for public funding sometime in the next year or two.

In the meantime, Atkins said he would hope state lawmakers take a closer look at public disclosure laws to hopefully reduce abuse of footage obtained by body cams or dash cameras.

“I mean, I’m all for somebody needing two months worth of data on an officer, because ‘this is the way they’re treating us,’ and we can look and see if it’s happening,” said Atkins, “but not just ‘all your data for two years, for no reason.’ And so we certainly don’t want anything that gets in the way of us being transparent to the community as to how we act and how we respond.”