Dr. Alan Melnick brought up a series of questions and concerns voiced by the community during the pandemic response

CLARK COUNTY — On Wednesday, Clark County Public Health announced they had won a national award for their use of social media in communicating with the community.

The Golden Post Award recognized the health department for best use of social media during an emergency during the 2018 measles outbreak.

That trend has continued during the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, which has stretched the public health agency to its limits.

Still, each daily update on the department’s Facebook page can generate dozens, if not hundreds of comments and questions. The department spends a substantial amount of time each day attempting to answer those questions.

Other times, questions from the community require a little more context than a comment on a Facebook post can fill.

At Wednesday’s Board of Public Health meeting, Public Health Officer Dr. Alan Melnick spent about half of his director’s report responding to some of the questions raised by the community in those comment sections, and through hundreds of emails sent to the department.

A frequent critic of the county’s handling of the pandemic is Rob Anderson, who goes by the moniker “The Recovering Pastor’’ in numerous videos posted to Facebook. He has repeatedly challenged Melnick to respond to a decision made last March to prohibit long-term care facilities from turning people away, even if they had potentially been exposed to an infected person.

A similar policy in New York led to accusations that potentially hundreds of elderly people at long term care facilities may have been exposed to the virus unnecessarily.

Nationwide, more than 90 percent of fatalities related to COVID-19 have been in people over the age of 60, and the first major outbreak in Washington state was at an adult care facility in Kirkland.

“I posted about it, and a director of a long term care facility contacted me saying that, you know, what happened in New York happened here in Washington, and I was stunned,” Anderson said in an interview with Clark County Today.

Anderson has accused Melnick of issuing a directive, ordering long-term care facilities not to turn anyone away, even if they had a pending COVID-19 test. At Wednesday’s meeting, Melnick said that part was untrue.

“The State Health Department issued guidance to nursing homes and long-term care facilities, asking them not to turn away residents with pending tests as long as they take precautions,” Melnick told the board. “We did not issue a directive. We just passed that guidance along to regional providers through a provider advisory.”

The goal, Melnick noted, was to preserve hospital beds for people needing acute care, rather than tying them up with people who had a pending test, especially since results could take up to ten days at that time in March.

Since Clark County hospitals have never been at risk of overflowing during the pandemic so far, it’s unclear how many potential COVID patients ended up at long term care facilities or, if they did, whether they were responsible for causing any outbreaks.

“Long-term care facilities have done a much better job of improving infection prevention practices,” Melnick said. “They know the drill, in terms of protecting their residents.”

Melnick also noted that most outbreaks at these facilities haven’t been caused by residents who test positive, but by staff members who may be spreading the virus while not experiencing symptoms.

Testing and case numbers

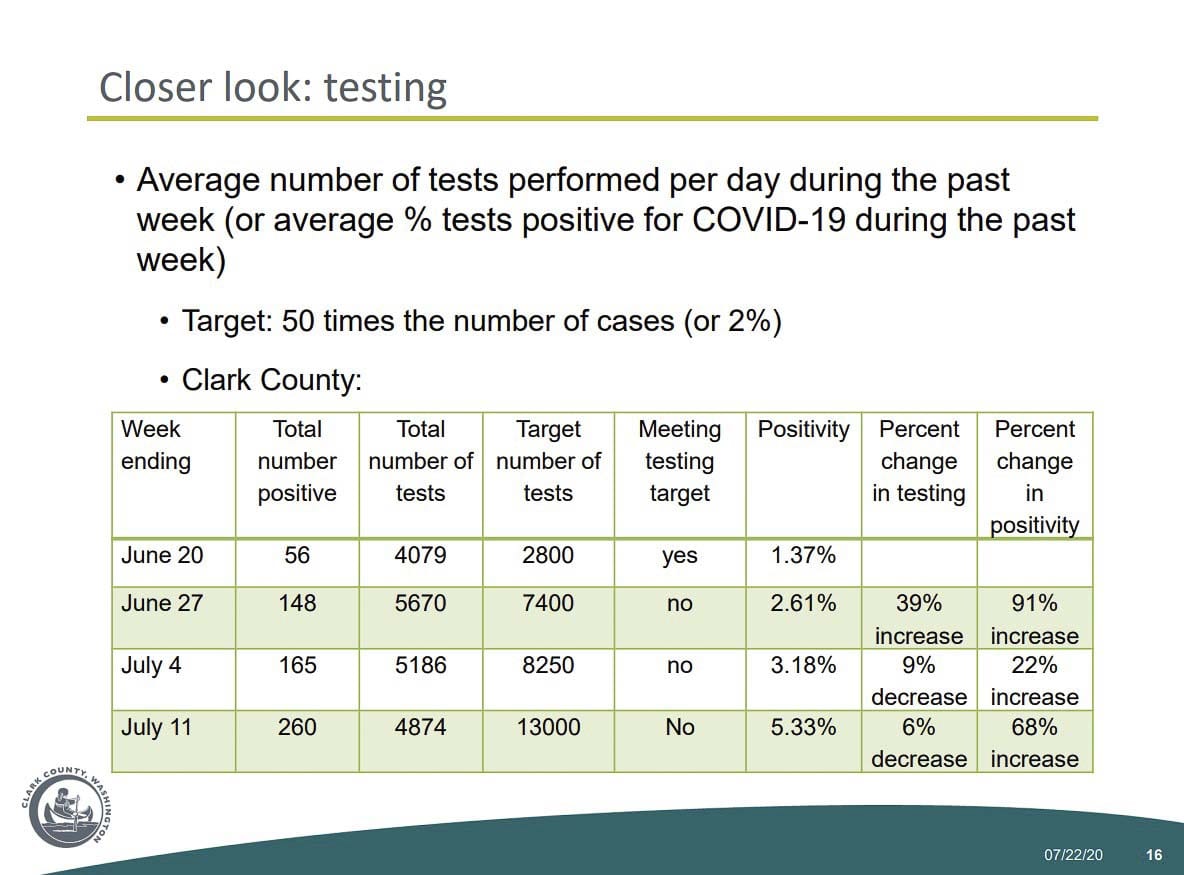

Another frequent comment, Melnick said, centers around whether the increase in testing can account for the rise in new cases.

“We’re seeing more cases, because there are more cases, not because we’re doing more testing,” Melnick said, pointing out a chart that showed the number of weekly tests has actually fallen since the last week of June, while the number of new cases per week rose by more than 80 percent.

The week ending June 20, 1.37 percent of tests were coming back positive for COVID-19. By the week ending July 11, that number was up to 5.33 percent. Total tests, week over week, had decreased by 6 percent, while the positivity rate rose by 68 percent.

“There might be a different way to portray this to the community,” said Melnick, “but I just want folks to know that there’s more disease, not because we’re doing more testing.”

The county has also recently faced new challenges with getting test results back in a timely fashion, Melnick noted.

“We actually issued a provider advisory last week, urging providers to use in-state labs,” Melnick said, “because we could get quicker turnaround.”

Many of the larger national labs, which might be less expensive for some providers, are experiencing turnaround times for test results of 7-10 days, as COVID-19 infection rates increase across much of the country, especially California and the Southeastern United States.

Those delays, Melnick added, inhibit the county’s ability to quickly do case investigations and contact notification, which can be critical in preventing someone who may be infected from exposing others before they begin experiencing symptoms.

Clark County is also facing a return to supply shortages, especially for testing kits. Things like gloves, masks, and gowns that the Clark Regional Emergency Services Agency (CRESA) had worked hard to secure. Some providers, Melnick said, are already dipping into supply reserves in order to continue providing testing for some patients.

Hospitalization rates

Another frequent criticism has been the way the county records hospitalization rates for COVID-19.

Currently, their novel coronavirus information page lists the number of people with a confirmed case, as well as people hospitalized with a potential case that are awaiting test results.

They also list what percentage of the county’s 669 licensed hospital beds are currently full.

Some have wondered whether hospitalization rates could be impacted by someone who shows up for a routine procedure and then tests positive.

“If they test positive before a non-urgent procedure, that procedure is rescheduled, and the patient is not admitted or counted in the hospitalization numbers,” Melnick clarified.

Another question centered around how many people who are hospitalized with a confirmed case are actually there due to the effects of the virus, or simply in the hospital for another reason after testing positive.

While Melnick said they don’t have concise data on that, his conversations with the directors of Clark County’s two largest hospitals indicates that the majority are there directly as a result of the infection.

“Whether COVID-19 is the cause of a hospitalization, if somebody has got COVID-19 and they’re in the hospital, they require the same kind of drill around infection control and PPE,” Melnick added.

Fortunately, even with the recent increase in cases, hospitalization rates have been largely steady in recent weeks.

COVID-19 mortality rate

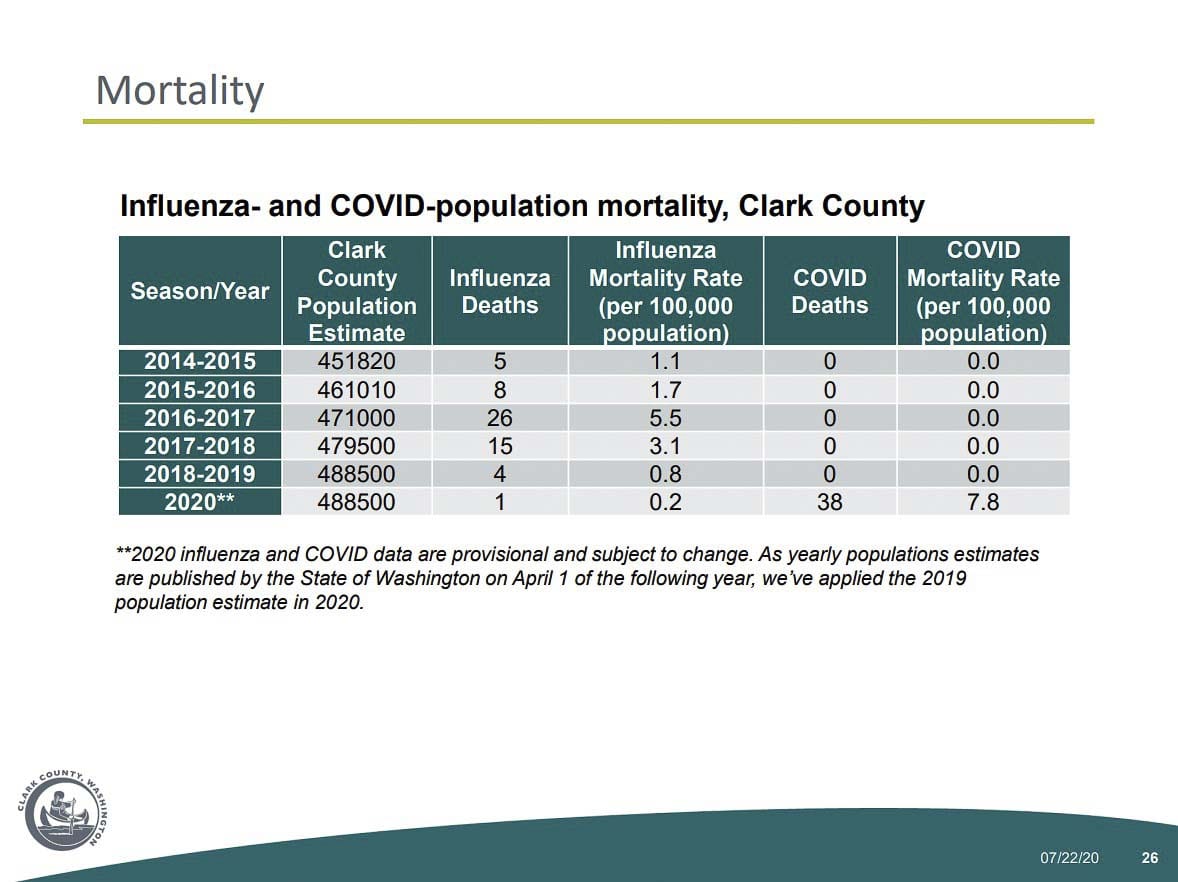

Another question the county has received frequently, said Melnick, centers around how the mortality rate of COVID-19. Some have alleged that, once deaths are taken into account and weighed against the overall population, the mortality rate of COVID-19 may be similar to that of a bad flu bug.

“Folks are taking the number of deaths and dividing it by the total population in our county, but that’s not really mortality rate,” said Melnick.

To get a truly accurate picture of the novel coronavirus’ mortality rate, he said, you would need to look at deaths over a much longer period of time.

The 2016-17 flu season was one of the worst in recent memory for Clark County, with 26 fatalities blamed on the virus. Compared to the county’s estimated population of 471,000 people that year, the mortality rate was 5.5.

With the COVID-19 outbreak just 4.5 months old, 37 deaths have already been blamed on the virus. That would put the mortality rate at 7.5, Melnick said, already making it worse than the worst flu season in recent history.

“So if we looked over the entire year, with what we’ve got going,” Melnick concluded, “the actual mortality rate is going to be much higher than that.”

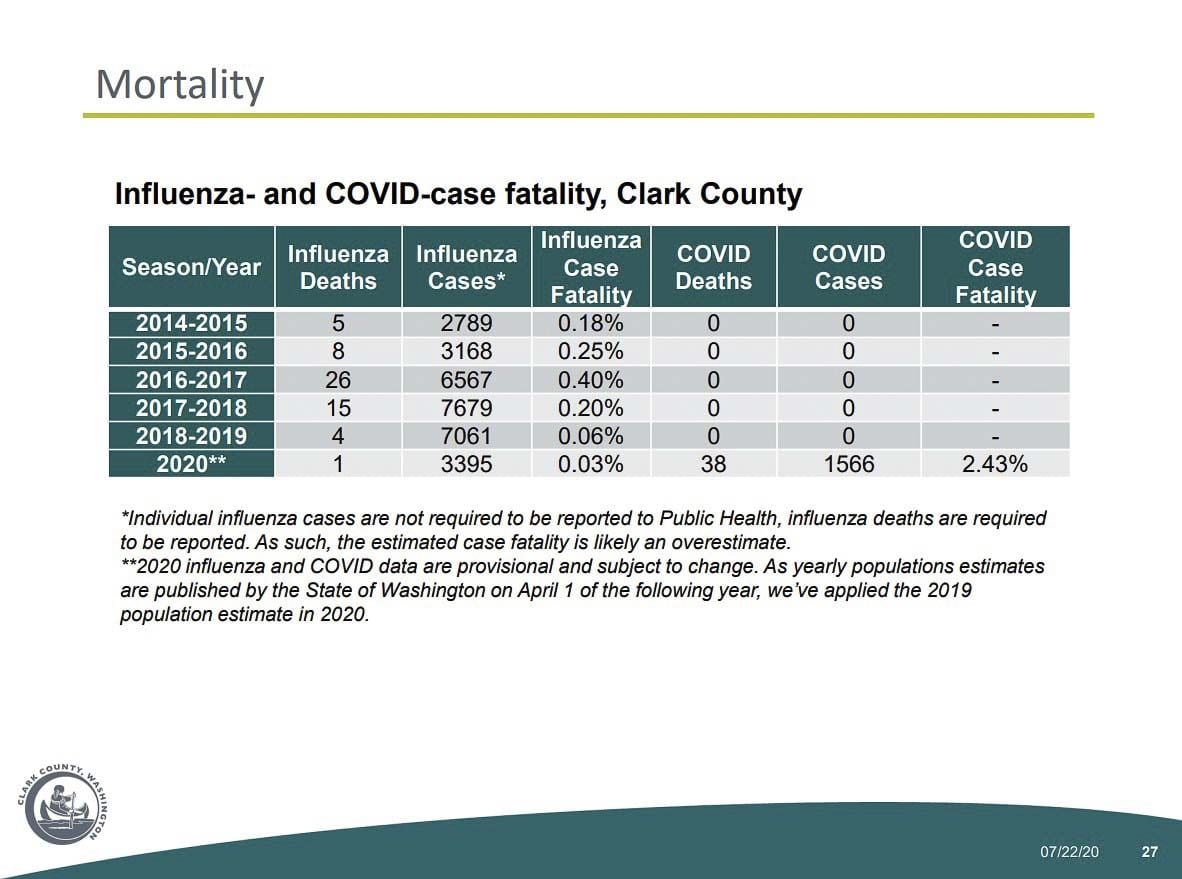

Even by the other measure of mortality, which takes total known cases compared to total deaths, the mortality rate of COVID-19 in Clark County has been just below 2.5 percent, compared to 0.40 percent in 2016-17.

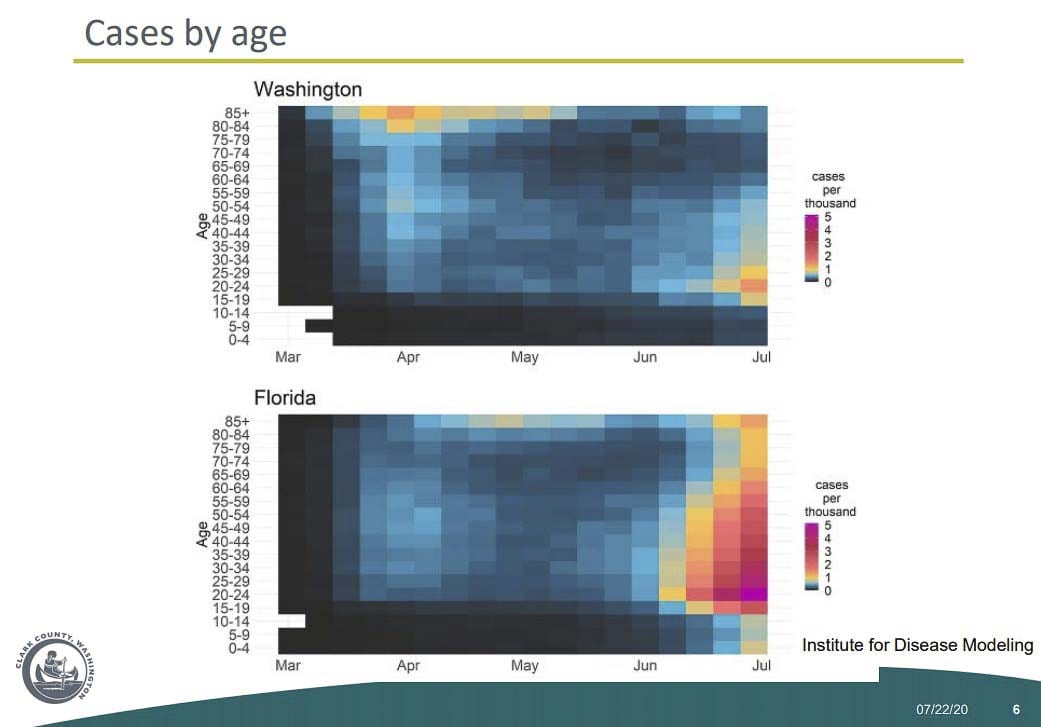

That rate has fallen in recent weeks, as younger people who are less susceptible to dying from the virus have gotten infected, but Melnick noted a study out of the Institute for Disease Modeling that looked at Florida’s outbreak.

It showed that the initial cases in late April and early May were in older people, before the outbreak initially subsided.

In mid-June, new cases started popping up, largely in younger people. Now, a month later, infections in older populations have begun to rise again, with a corresponding increase in the number of daily deaths.

“My big concern is, being a few weeks behind Florida, that there’s a good likelihood in Washington state, if things continue as they are, we’ll begin to see older populations affected,” said Melnick, “and we’ll begin to see the strain on our hospitals and our critical care bed capacity, just like we’re seeing in Florida.”

Nationwide, COVID-19 related deaths have topped 1,100 for three straight days, bringing the total to nearly 150,000 people, surpassing strokes to become the fifth leading cause of death in America this year.

Heart disease and cancer each kill well over half a million Americans each year, but it’s likely that COVID-19 will surpass accidents (170,000) and lower respiratory diseases (160,000) in the next few weeks.

“This is not a disease to be taken lightly,” Melnick concluded. “It is a significant cause of death in the US.”