The first of the three sessions featured speakers from several outreach organizations

CLARK COUNTY — The first of three listening sessions on systemic racism focused largely on the history of institutional racism in and around Clark County.

Held remotely last Friday, the session was the first of three scheduled in front of Clark County Councilors. This one featured speakers from the NAACP of Vancouver, YWCA, the Southwest Washington League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), as well as the Clark County Volunteer Lawyers Program (CCVLP).

Two more listening sessions, scheduled for later this month, will allow members of the public to answer the question, “How has systemic racism in Clark County impacted you?”

The first of those, on Wed., Aug. 12 from 6-8 p.m., will be recorded. A third listening session, on Wed., Aug. 26 from 6-8 p.m., will be private, though a summary will be released, with the names of individual speakers removed.

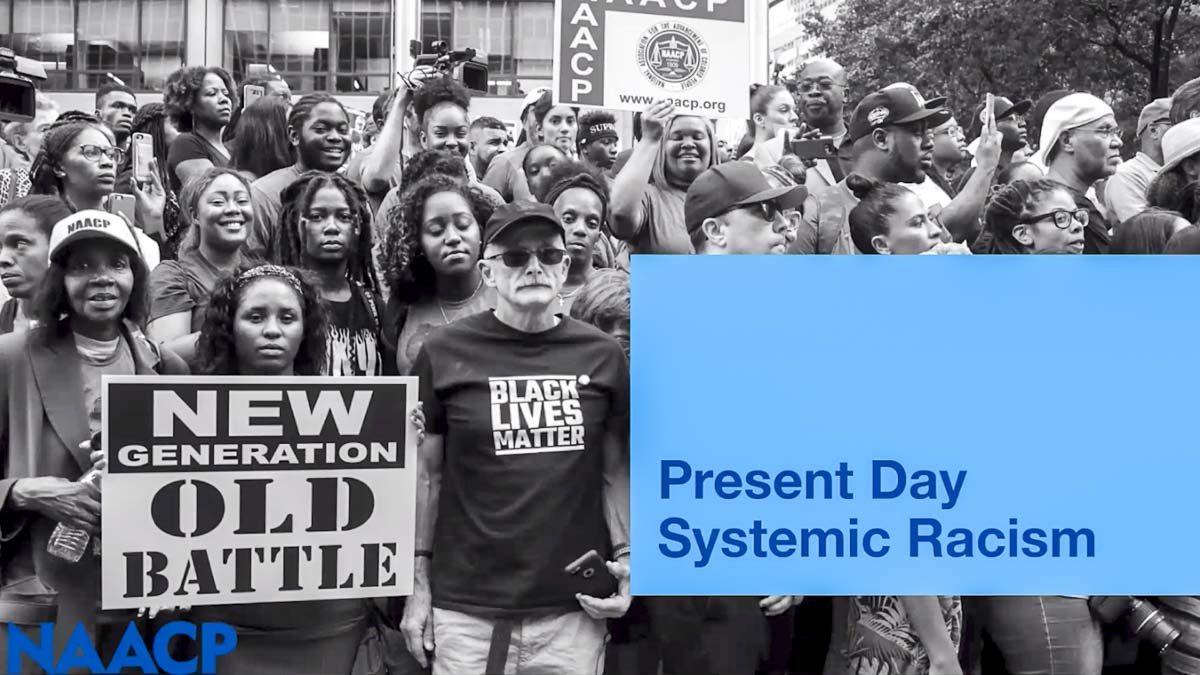

The first session focused largely on testimony about the history of systemic racism in Clark County, and evidence of its existence today in jail populations, school discipline rates, as well as healthcare and housing disparities.

Moderator Nancy Retsinas noted that systemic racism, which is also referred to as structural or institutional racism, refers to the ways in which “the joint operations of institutions produce racialized outcomes, and perpetuate white supremacy.”

“These systems historically used race to justify policies and practices that have enabled class delineations in society,” Retsinas added, “and those delineations oppress people of color.”

The evening’s only fireworks came after Tim Murphy, a member of the NAACP Legal Redress Committee, noted that “systemic racism in Clark County is alive and well today,” adding that it is seen through police shootings, mass incarceration, school discipline, and “through the council chair, espousing ignorant and dangerous viewpoints, denying the existence of an indisputable fact.”

That comment drew a response from Council Chair Eileen Quiring, who noted that the council’s rules of decorum prohibited “demeaning remarks.”

Murphy defended his comments as “descriptive,” but Retsinas reminded the speakers that the goal of the listening sessions was “dialogue and not debate.”

Continuing on, Murphy cited a recent review of the Vancouver Public School system’s disciplinary practices, which showed that students of color were 2.2 times more likely to be suspended or expelled than white students.

“It highlights how this is not an issue of the past at all, though it certainly has a very long history,” said Murphy, “but it’s an issue of the present and it will be of the future because this county has not been able to reckon fully with systemic racism.”

Asked if similar issues had been seen at other school districts, NAACP of Vancouver vice president Jasmine Tolbert said there had been “verbal” reports of similar issues in districts such as Ridgefield, Camas, and Battle Ground, though she didn’t have detailed reports on hand.

In terms of criminal justice, Murphy noted that black people are greatly over-represented in the Clark County prison population, making up 9 percent of inmates, while comprising just 2.4 percent of the county’s general population.

“It’s not behavior, the issue is race,” said Murphy, citing a statistic that black and white populations use marijuana at similar rates, but black people are three times more likely to be charged and sentenced for possession.

Those higher incarceration rates, Murphy noted, create disparities in housing, with criminal convictions making it more difficult to rent or buy property.

“Our system doesn’t allow people to get out of poverty by trapping them in it because they must pay off fines in order to clear the record,” said Murphy. “And for people who are low income that’s simply not possible in many cases.”

Vanessa Yarie with the YWCA of Clark County tied into Murphy’s comments, noting that higher incarceration rates amongst black people also creates more single-parent households, and more childhood trauma for the children of people with a criminal history.

With the average cost of preschool in Clark County running around $800 a month, she added, the children of many families living below the poverty line face an uphill battle due to a lack of early childhood education.

“We’re starting to see how these things tie together into people’s lived experiences today,” Yarie said, adding that domestic violence and divorce are not the only traumatic events children of color face. “They’re also things like historical trauma, which is basically systemic racism, and social conditions.”

Those experiences, known as Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACE, lead to social, emotional, and even cognitive impairment, said Yarie, creating poor health outcomes and even earlier death rates.

In her comments, Tolbert provided more of the historical context for systemic racism in Clark County, recalling policies aimed at preventing mixed marriages, and a tight connection between the Ku Klux Klan and county leadership in the 1920s and ‘30s. In the 1940s, she added, arriving black families often faced barriers to housing, including receiving threats.

“That’s where the NAACP was actually formed here,” said Tolbert, noting that, “there were protests, but these protests are what impacted things being done, affirmative action being enforced.”

While Tolbert admitted that many of these racist policies have been overturned or addressed in the past 50 years, she said they created a foundation of racism that continues to impact area populations.

“By acknowledging that it is present, and these systems were created by racist people,” she said, “we are then able to fight and move forward and change these items.”

Other speakers focused on the impact of systemic racism on groups other than black people.

Jeffery Keddie with the Northwest Justice Project noted the use of Federal authority to seize land from Native Americans, largely through the “discovery doctrine.”

“The Discovery Doctrine said European powers gained radical title or sovereignty to the land they discovered,” Keddie recited. “So the discovering power gained the exclusive right to extinguish the right of occupancy of indigenous occupants.”

Keddie noted that the policy had impacts for local native populations as well.

“Systemic racism allowed the dispossession of native lands in what is now called Clark County, Washington,” said Keddie. “And Vancouver, Washington is located within the ancestral territory of the Chinook, Klickitat and Cowlitz people, among other tribes.”

According to Keddie, the seizure of native lands led to a massive wealth gap, creating disparities that still leave many Native Americans struggling.

Elizabeth Fitzgerald, with the Clark County Volunteer Lawyers program, noted that black families make up 12 percent of evictions in Clark County, while making up just 2.4 percent of the population. While Hispanic and Latinx populations are less likely to be evicted, they did often report threats from landlords to “call ICE on them if they do anything from report poor living conditions like vermin or lack of running water, question any additional costs or fees … or report safety concerns with neighbors of the same apartment complex.”

“This is a prime example of social enforcement,” she said. “Having the power to prey on people’s fears, harness power, and prevent community members from exercising their rights.”

At Tuesday’s meeting of the Clark County Council, Councilor Gary Medvigy said he had been exploring the work that Evergreen School District has done in addressing expulsions and discipline to account for racial disparities. Medvigy, a retired judge, sits on the Juvenile Justice Committee, and said he hoped to explore the issue further in that group.

“I’m hopeful that there’s some good informed changes that they’ve made that can be exported to some of the other school districts,” Medvigy said.

Chair Quiring said she would be interested in having Clay Mosher, a sociology professor at Washington State University Vancouver who has done work in the field of juvenile justice and consulted with Evergreen School District, speak to the full council after that JJC meeting.

“I think it’s good information to have,” Quiring noted, “and certainly it would be great if Evergreen can collaborate with the other districts to implement what they have been able to do.”