Council lacks votes to overturn the 2014 ban

VANCOUVER — It appears Clark County’s ban on marijuana businesses will remain in effect for now. The moratorium, passed in 2014, makes it illegal to operate marijuana-related businesses in unincorporated Clark County, though they are legal within the city limits of Vancouver and Battle Ground.

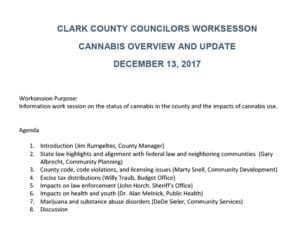

At a work session last December, the members of the County Council heard from law enforcement and local health officials on the impact of the cannabis industry locally and across the state. The next step was supposed to be a public hearing on a proposal to overturn the moratorium sometime in February, but it never happened.

There was speculation the decision last January by Attorney General Jeff Sessions to reverse the Cole Memorandum prompted County Chair Marc Boldt to step away from the issue, but he tells Clark County Today that’s not the case.

“I had like four meetings with prevention groups,” Boldt says, “and then we had a county-wide prevention meeting about two months ago, and so I put out the question, ‘what do you think about the moratorium'”?

Boldt says the reaction in those meetings, as well as conversations with Sheriff Chuck Atkins, members of the local Salvation Army, and the Superintendent of Ridgefield Schools Nathan McCann, led him to believe that the ban needed to remain in effect.

“I mean we’re the Board of Health and everything else,” Boldt says, “so it just really goes against our grain to say ‘alright, we know we want to keep kids clean, but at the same time we’re going to legalize it.’”

In the 2017 Fiscal Year, the city of Vancouver received $524,791 in tax revenue from the sale of marijuana. Battle Ground received more than $25,000. That money currently is fed back into local police, largely for drug enforcement. But the county doesn’t receive anything.

“It’s the county’s responsibility to do drug and alcohol treatment, and we don’t get any of that money,” Boldt points out. “We get some money from the state … basically they’re making all the money and it’s really affecting our kids.”

How much it’s affecting kids is still up for debate. The December work session also included data from the Healthy Youth Survey, which showed the number of 8th and 10th graders in Clark County who say they’ve smoked marijuana recently has actually decreased since it was legalized. The number of teens who see the drug as difficult to obtain also increased significantly. But the same study also found that kids were nearly twice as likely to see marijuana as less harmful than in the decade before it was legalized.

District 3 Councilor John Blom says he was one of two council members, along with Julie Olson, who wanted to at least go ahead with the public hearing.

“Given the new data we have from the Healthy Youth Survey,” Blom says, “and from the revenue numbers, it would be a good time to at least have the discussion.”

Blom argues the Clark County moratorium likely has had little impact, given the fact Vancouver and Battle Ground allow marijuana businesses.

“I don’t feel like we’re making a whole lot of sense to say it’s illegal on one side of the street, but it’s legal on the other side of the street,” he says. “That doesn’t seem like a really strong message in terms of deterrent.”

The view of law enforcement officials

The county estimates removing the moratorium could bring in close to a quarter of a million dollars each year in revenue, which would be used for drug treatment programs. But, at least from the view of the sheriff’s office, it’s not worth it.

“The production has gone way up, and the illegal sales have gone way up,” says Commander John Horch with the Clark-Vancouver Regional Drug Task Force, “and with that, with all the money and drugs, we’ve had increased violence potential too.”

Horch spoke at the December work session, saying the sheriff’s office has seen a dramatic increase in drug-related complaints since marijuana became legal in Washington state. Those range from odor complaints, to reports of illegal grows. In Spring of 2016, an Easter egg hunt in Salmon Creek was interrupted when a dispute over a black market marijuana grow ended with people aiming guns at each other in the midst of egg-hunting children and adults.

“Most counties, and most governments, aren’t prosecuting even illegal grows,” says Horch, “because they feel time and effort should be spent on other things, which it needs to be. So that’s why it’s opening the floodgates. They’re growing, they’re selling, and the black market is through the roof.”

Councilor Blom says that’s actually one argument in favor of removing the ban.

“Clearly there’s money flowing right now with the ban into markets we don’t want it in,” says Blom. “When we were up at the Washington Association of Counties conference last Fall, one of the presenters on the topic was talking about the fact that in areas where it’s legal, they’ve actually seen less of it when they’re doing major drug raids … In areas where it’s legal it’s actually reduced the black market demand.”

Horch says he’s heard differently from other drug task force commanders across the state. They feel the black market problem has gotten universally worse, thanks in part to the steep taxation of legal marijuana that can make it less expensive on the black market. And with marijuana still illegal in many states, there’s strong financial incentive for illegal grows. Many of those happen on county land, sometimes diverting public watersheds for irrigation, and using chemicals that are harmful to the local environment. They are also often protected with guns, and lots of them.

The Liquor Cannabis Board (LCB) is also having difficulty in keeping up with enforcement of growers and sellers. Horch says they’ve run into long delays when seeking assistance from the state with complaints about illegal operations. And Boldt says there is still far too much of a disconnect between what’s happening at the state level and the local level.

“They approve all these licenses, even though the county has a moratorium on it,” Boldt says, “so a person will go up there and get a license, and come down here and rent a place. Then they try and get a permit, we say no, so that needs to be cleared up.”

Sticky’s Pot Shop in Hazel Dell

One such case was Sticky’s Pot Shop on Highway 99, outside of the Vancouver city limits. They’ve been in and out of business as their dispute with the county works its way through the courts. Initiative 502, as approved by the voters in 2012, provided little clarity about whether local municipalities could pass their own bans on marijuana businesses. While the state’s Attorney General later issued an opinion in favor of the local governments, that statement is not binding.

The state’s court of appeals is currently debating whether Clark County is within its rights to ban Sticky’s from operation. Should they rule in favor of the business, the moratorium may be a moot point.

Boldt says I-502 even leaves open the question of whether marijuana operations in Vancouver and Battle Ground are violating the law by transporting their products through unincorporated Clark County, where it’s still illegal.

“There’s a lot of stuff I wish the legislature would work on,” says Boldt, “and even the Federal government.”

All sides seem to agree that more information is needed to truly understand what the long-term impact of marijuana will be, both from a health standpoint, and an industry one. Traffic crashes and fatalities are up sharply in many places where marijuana is now legal, but the data is only a couple years old so it’s difficult to know if correlation equals causation. Health officials also worry that the effect of marijuana on developing brains may be more severe than we’ve previously believed.

What isn’t up for debate is the success of marijuana sales as a revenue stream for the state. Just three years after legalization, the state of Washington expects to have earned well over $700 million in tax revenue between now and the end of next year. Around $30 million will go to local governments, with the rest going to fund healthcare, medicare, marijuana abuse programs, and the Liquor and Cannabis Board. Unless the Federal government under President Donald Trump decides to enforce its prohibition on marijuana, it’s highly unlikely that states will be willing to reverse course.

At last for now it appears Clark County will remain one of only a handful in Washington state to continue banning recreational marijuana sales, despite the lure of the revenue it could bring.

“It’s weighing the money on one side, and the purpose of the county on the other,” says Boldt, “and I just went with our main focus.”

Boldt says he’s open to the discussion if the council wants to hold one, but right now they wouldn’t have the votes to overturn the ban.