Eric Temple and the county are set to mediate their lease agreement, but both sides appear resigned to a potential legal fight

BRUSH PRAIRIE — It wasn’t that long ago it seemed as if Clark County and the operator of the 33-mile Chelatchie Prairie rail line were headed for a happy conclusion. Now, they may be headed for court.

Things have become so acrimonious that Eric Temple, president of Portland Vancouver Junction Railroad, which operates the Chelatchie Prairie line, has accused the county of “attempted extortion that would make John Gotti blush with pride.”

We’ll get to the present situation in a moment. First, a little bit of history.

The county’s relationship to the parts of the short line railroad they own has long been a rocky one. It has also, generally, been a money loser.

Clark County purchased the 33-mile rail line over several years in the 1980’s, after the existing owner announced plans to dismantle the track and sell it off. The county had planned to operate the rail line for commercial, tourism, and recreational purposes.

Despite the best intentions, ownership of the rail line has largely been a money-losing proposition for the county.

In 1997, the county hired Mainline Consulting to look into options for the line as their lease with the existing operator was set to end soon. Mainline suggested they pay a new operator a guaranteed profit, then share revenues when industrial development along the line could be achieved. The then-County Board of Commissioners decided the option would cost too much without any guaranteed return.

Five years later, Mainline Consulting was called in again. This time they recommended that the county seek out an operator that would be willing to maintain the line at a loss, with the promise of a larger cut of the profits from industrial development.

Enter Temple and Columbia Basin Railroad, who says his company was the only one, out of 400 approached by the county, willing to take on the lease to operate the line.

“If this deal was so unfair to the county and so overly generous to the railroads, why did they all walk away?” he asks.

The deal with Columbia Basin Railroad, which eventually became Portland Vancouver Junction Railroad (PVJR), essentially guaranteed the county would actively pursue industrial development along the southern portion of the route in Brush Prairie. Meanwhile, PVJR continued a sublease with Battle Ground, Yacolt and Chelatchie Prairie Railroad (BYCX) to operate their popular Chelatchie Prairie tourist trains on the northern part of the track.

Temple says his contract, which is a 30-year lease with options for two more 30-year periods, included a guarantee that the county would eventually develop along part of the line.

“This is a warranted item in the contract,” he says. “It’s not something subtle, it’s an entire section of the contract.”

That contract is now the primary focus of mediation between PVJR and the county, set for March 11. Last December, an attorney for Friends of Clark County raised some doubt about whether the lease agreement with PVJR had ever been signed by the Board of Commissioners. A county attorney issued their opinion that the lease was likely invalid. That led Temple to force BYCX to stop their popular Christmas Tree trains temporarily over concerns about whether their insurance was valid.

It’s not the first time PVJR and BYCX have been at odds. Documents obtained through a public records request show that disagreements over indemnity were an issue as far back as 2005, shortly after PVJR took over as operator of the line. Eventually, the county stepped in to cover the additional insurance PVJR felt BYCX needed.

Conflict with Eric Temple is also not something the county is unfamiliar with. The entrepreneur has a track record of drawing outside of political lines to get things done, which appear to have rubbed county staff the wrong way at times.

Some of that included lobbying that eventually led to the passage, in 2017, of a bill that amended the state’s Growth Management Act to allow industrial development along short line railroads. Temple was a driving force in getting that done, more than a decade after the county had promised to pursue the amendment.

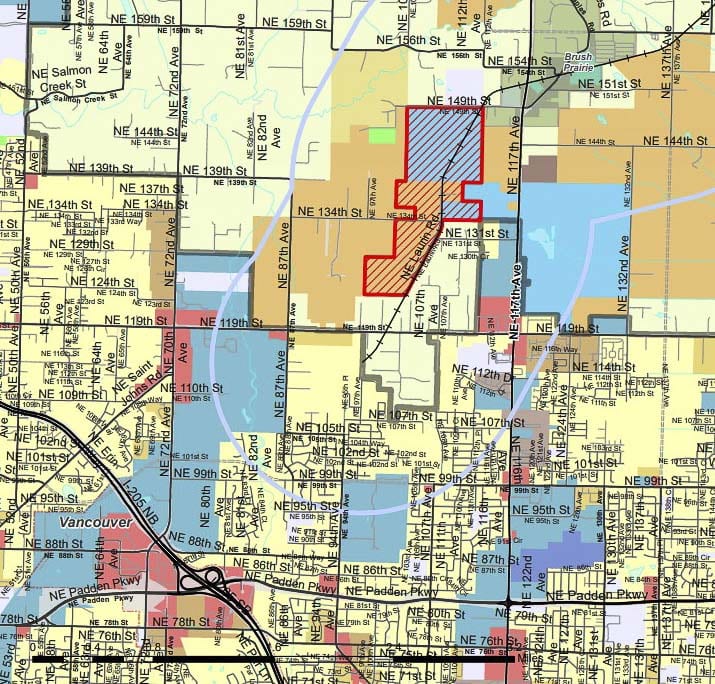

It took nearly a year after the governor signed that bill for the county to even begin the process of figuring out how to rezone land along the rail line south of Brush Prairie, and how much land should be included. Again, Temple rubbed some people the wrong way as a non-voting, ex-officio member of the Freight Rail Dependent Uses committee, when some members felt he was controlling the conversation too much.

Ultimately, the committee returned a recommendation of a much larger FRDU zoning overlay than the county had initially proposed. That expanded overlay was ultimately rejected as the county moved forward.

Then in December things seemed to derail, as it were. Then-county Chair Marc Boldt crafted a resolution condemning Temple and PVJR for their move to stop the Christmas Tree trains from running amid the questions over their lease. Temple fired back, saying the county was choosing to crucify him, rather than simply coming to the table and fixing the situation.

Temple says he was able to obtain the original lease agreement from the county, and that his attorneys tell him it is fully valid and still in effect.

Ultimately, both sides agreed to abide by the existing lease for 90 days, while they worked through the issues. That led to the March 11 mediation, though neither side seems confident that anything will come of it.

At the council’s Tuesday meeting last week, County Manager Shawn Henessee mentioned the meeting. He has not responded to ClarkCountyToday.com’s request for any further comment on the matter.

County Chair Eileen Quiring responded via text message, saying “My hope is that we can reach an agreement with the lease and move forward. I’m disappointed that Eric stayed (sic) that he doesn’t seem to think there can be a resolution.”

So who does Temple blame for the current sad state of affairs? The new county manager.

“Shawn is coming into this county and wants to make a name for himself,” says Temple. “But frankly, the only name he’s earned so far is Unemployed.”

Quiring insists that the county is not trying to force Temple or PVJR out of their position as operator of the rail line, but that there are portions of the lease that need to be “fixed” in order to comply with county code. She did not detail what those issues may be.

For his part, Temple says the county has failed to live up to their own obligations when it comes to the lease agreement. For instance, he says one of the train trestles, known as Bridge 12, is close to failing, and the county has done nothing to fix it. He calls that “a classic example of the county failing to perform at virtually every level of this lease.”

Temple says he went to the state and secured $2.8 million in funding but then was told by the county that the price had gone up and they needed more. His response was that they should have thanked him for the work he did, and then sent their own lobbyists to get the extra funding.

Readying a lawsuit

Temple says he’s so pessimistic about the chances of an agreement coming out of next month’s mediation session that he’s already preparing a lawsuit seeking over $100 million in damages from the county. And he says he has proof that the lease is fully valid.

According to Temple, the county is being “penny wise and pound foolish,” by quibbling over a small amount of money while he has businesses lined up ready to develop in the area. He estimates a fully developed FRDU overlay would bring in over $27 million in property tax revenue for the county, compared to just under $900,000 in 2018.

“I estimate so far they have basically pissed away $33 million that they could have captured otherwise,” he says. “And they’re worried about a couple hundred thousand dollars? Seriously?”

Temple has also pushed back against plans to build a pedestrian bridge along the rail line, saying it is a violation of his lease agreement. While he’s not opposed to trails eventually being built there, Temple says the county needs to complete the rezoning process first. In messages to former Public Works Director Heath Henderson in August, Temple said he worried building trails before the rezoning process was complete would increase opposition to development by people who live in the area.

According to Temple, he has heard very little from the county since December, largely on the advice of their legal counsel. But he insists that there are those who now view his lease as detrimental to the county, and advantageous to PVJR, should the freight rail dependent zoning overlay go through.

“They wanted me to take all the risk, and so I did,” says Temple. “But once again, risk-reward.”

Under the existing lease agreement, PVJR only has to pay the county once it surpasses 1,000 rail cars on the line. At that point, they pay $10 per car for the next 1,000.

“They basically offered to cancel my existing contract, and then sit down and negotiate a new one,” he added. “Which, as you can imagine, didn’t sit well with me. Because once my contract is canceled, then what? I basically have lost all my investments the second I do that.”

Under the existing lease agreement, PVJR does not pay Clark County a fee to operate the rail line that the county owns. If PVJR reaches 1,000 rail cars per month, they would then pay $10 per car for the next 1,000.

“If you haven’t been here the past 15 years it looks like I’m somehow taking advantage of them when the opposite is true,” Temple says, insisting he has invested millions in upgrading the rail line, in hopes of eventually making a profit when freight rail dependent development is allowed.

“The contract was fine with them as long as I was losing money, but the second it appeared I was going to make money there was a problem there,” says Temple, while accusing the county of trying to steal 15 years of his life and a major monetary investment. “As if I hadn’t added a lot of value to this railroad that now they’re going to slide that on their side of the ledger and start the whole process over.

“I’ve got 15 years and millions of dollars invested in this,” he adds, “and what they’re trying … it’s unethical.”