Train and transit ridership decline especially in COVID-19 era

A Portland-to-Seattle to Vancouver, BC high speed rail line took another small step forward last week.

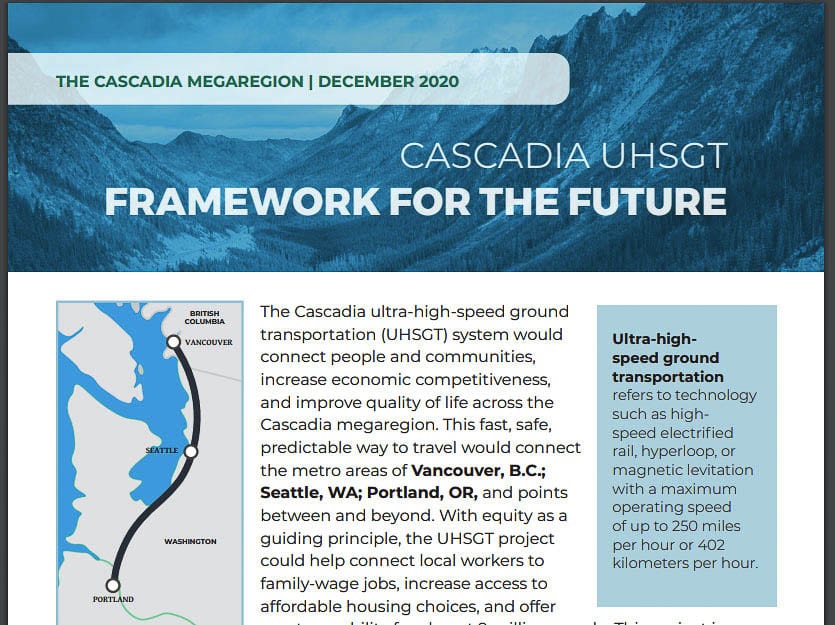

Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia are studying how ultra-high-speed ground transportation might serve the Pacific Northwest. A 2018 study estimated capital costs for the project ranging from $24 billion to $42 billion in 2017 dollars.

Ultra-high speed ground transportation refers to technology such as high speed electrified rail, hyperloop, or magnetic levitation with a maximum operating speed of up to 250 miles per hour.

The report builds on previous state-sponsored studies that asserted there is “sufficient demand and a business case” for trains running at up to 250 miles per hour between Portland, Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia. A WSDOT 2017 report indicates between 2.8 million and 3.2 million annual riders in 2055, in their “primary corridor.” Fifty percent of that ridership was between Portland and Seattle. They propose 12 daily round trips.

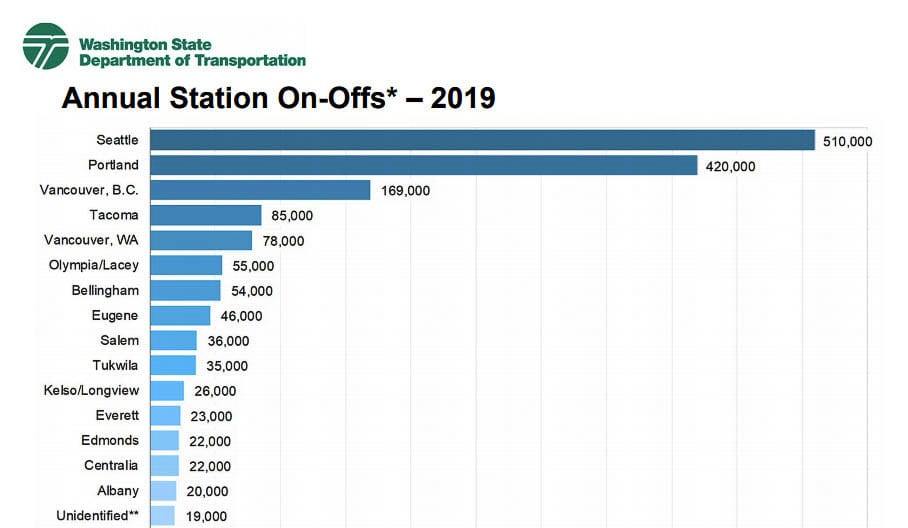

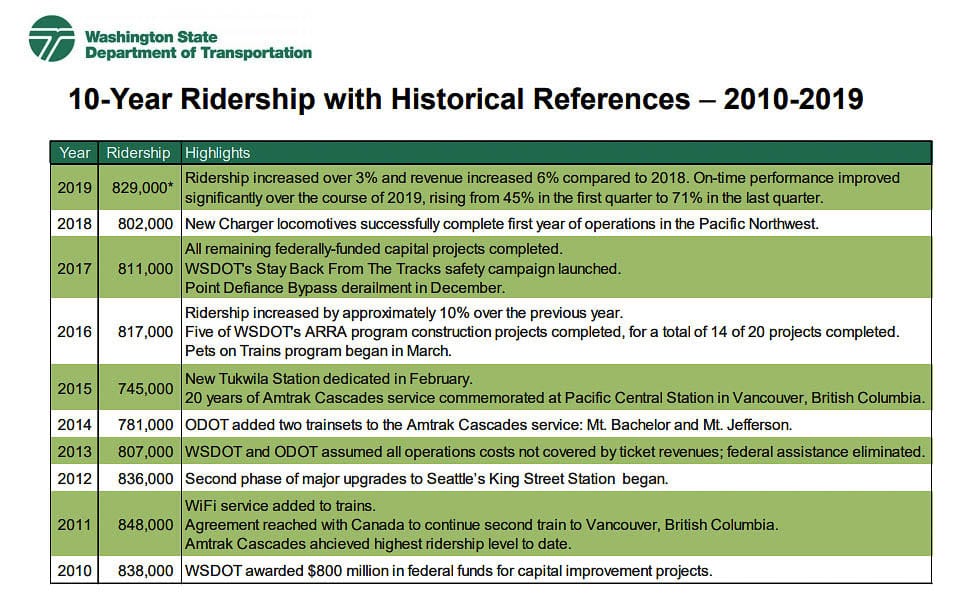

Consultant WSP USA bases their recommendation in part on projected ridership of three million annual riders in 2055. Yet the current Amtrak ridership on the Cascades line is 343,497, a 57-percent decline from 2019. Two years earlier, ridership was 810,000. That’s less than 1,000 passengers a day presently.

Half of the ridership is between Portland and Seattle, or about 470 daily passengers today. A quarter of the ridership is between Seattle and Vancouver, BC.

Compare that with almost 305,000 average daily crossings of the Columbia River in 2019, according to the SW Washington Regional Transportation Council.

Many citizens are skeptical, having watched the exploding costs and delays related to California’s high speed rail effort. (here).

“Let’s be real. The current project, as planned, would cost too much and respectfully take too long. There’s been too little oversight and not enough transparency,” California Governor Gavin Newsom said in his Feb. 2019 State of the State Address. The project had ballooned to potentially $98 billion, triple the original $33 billion cost estimate (2006) of the project.

An OPB news report last week on the Cascadia project suggested it’s “time to move to the next level, or “kill this thing right now.’’

The three states and Microsoft paid WSP $895,000 for the study. WSP might sound familiar to readers, as they are the consulting firm hired to oversee three major Portland metro area transportation projects. The Interstate Bridge Replacement Project, the I-5 Rose Quarter project, and the I-205/I-5 tolling project.

The study lays out multiple options including traditional high-speed rail, magnetic levitation trains or a hyperloop, in which passengers zip along in capsules that are propelled electrically down sealed low air pressure tubes. The travel times suggested are about one hour between Portland and Seattle and another hour from Seattle to Vancouver, British Columbia.

The vision for frequent bullet train service between the Pacific Northwest’s biggest cities contrasts with the grim state of current Amtrak service in the region. In October, Amtrak cut the frequency of its two long-distance lines serving the Northwest. The Empire Builder and Coast Starlight went from daily service to three times per week due to steep declines in ridership during the pandemic reports OPB.

Furthermore, all forms of mass transit experienced significant declines in the era of COVID-19. The Cascade Policy Institute reported last week on Portland’s light rail.

“Peak-hour ridership on all MAX lines during October was down 72% from a year ago. Unlike driving levels, which have nearly returned to normal, transit ridership has remained depressed over the past 9 months. Transit riders have simply moved on to other options.

Rail transit in particular requires high levels of both residential and worker density, but COVID has induced a mass exodus of workers from downtown Portland. Many of these changes will become permanent. Employers have discovered that remote working is not only feasible, it’s preferred by many employees.”

The rationale for the Cascadia high speed rail was in part made by this WSP statement. “The Cascadia region is facing an unparalleled health, economic, climate and social justice crisis that requires rethinking the status quo and developing new ways of doing things.” Citizens might wonder how an expensive high speed train would solve health or climate or social justice problems.

The report cites 3 million annual passengers 35 years from now, as being enough potential riders to justify the construction. That would be 8,219 daily passengers, of which half or 4,100 passengers would travel between Portland and Seattle if future ridership mirrors present day travel patterns. That would be almost a 9-fold increase from the 470 daily passengers today.

How to pay for it remains a significant issue. The report indicates an unknown level of funding from the U.S. and Canadian governments. For the two states and province, they list regional property tax increases, a carbon tax or statewide cap and trade program, road usage charges, and congestion pricing as funding ideas.

They also mention “private contributions” — funding provided by a private entity with no assumption of repayment.

Cost projections are listed in 2017 dollars. No timeline is offered for construction. One would expect the $24 billion to $42 billion price to increase significantly due to inflation, perhaps doubling by the end of construction.

The 77-page document cites the Columbia River Crossing and hails the “restart” of the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project. (Remember, WSP is the consultant on that project as well.)

An interesting side note is that presently, Canada does not have any high speed rail service. One would think travel into the U.S. east coast business corridor of Montreal to New York, and Washington, DC would be the primary candidate for Canada funding its first project.

In 2017, Washington spent $700,000 on the project. Funding was $750,000 in the 2018-2019 budget, and an “approximately equal share of the $895,000 in 2020.

The private sector airlines presently offer 727 flights per week between Portland and Seattle according to a Google search. That’s over 100 flights per day offering roughly 7,000 seats. The flight time is about 30-35 minutes. Fares often run under $100, with fare sales on low travel times at $49. There are 289 weekly flights between Seattle and Vancouver, BC or 41 flights a day.

There is also Flix bus service offered between the two cities on weekends for $11.99 per trip. Greyhound offers daily service for $21 to $29 per trip. Bolt Bus offers a couple trips per day for around $25 per trip. According to Busbud, there are six daily bus trips between Seattle and Portland for an average price of $25 per trip. Travel times vary from four to six hours.

Taxpayer costs are minimal for these services. When travel demand changes, as during the pandemic, the airlines either move the airplanes to other routes, or simply park the airplanes. Ditto bus lines. Government run transportation on fixed routing does not have this flexibility.

A different example is the Washington state ferry system. In 2019, prior to the pandemic, ridership declined by 800,000 customers, a 3.2-percent drop to 23.9 million.

In an August press release on ferry ridership, WSDOT reported “current system ridership is nearly 60% of what it was this time in 2019 with the number of vehicles carried a little higher at nearly three-quarters of 2019 vehicle ridership. Walk-on passengers are hovering around one-quarter of last year’s numbers.”

Amtrak has a history of service issues and losing money for decades. Amtrak recently projected a fiscal 2021 ridership of just nine million, a 72-percent decline from 2019’s record 32.5 million passengers. Most of their riders travel on the east coast. They will move to three-day-a-week service for most long-distance trains.

Presently, Amtrak reports Seattle-to-Portland passenger traffic is half the system ridership, but that route provides only one third of system revenue.