Over five years, salary and benefit costs in the Camas School District have increased 51 percent with a 14-percent increase in full-time employee equivalents

The Camas School District (CSD) is asking voters to approve two property tax levies on a Feb. 9 special election ballot.

Literature from the district indicates the three-year levies will replace current levies that expire at the end of 2021. These are often known as “enrichment levies,” because the state, theoretically, provides adequate funds for “basic education.”

The McCleary decision was the result of a lawsuit against the state of Washington. The case alleged that the state had failed to meet the state constitutional duty “to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders.”

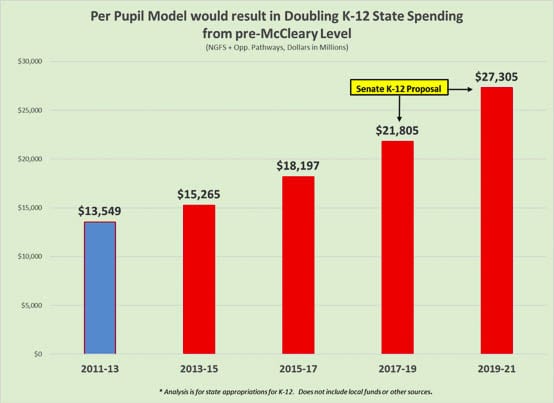

In response to the January 2012 Supreme Court decision, the 2013 legislature provided state schools $15.2 billion in state funding, an increase of $1.6 billion, or 11.4 percent, over the previous budget. Overall, state funding per student rose from $6,782 in 2012-13 to over $11,500 for basic education in 2019. The state also adds funding for school buildings via its capital budget and other funds for special education programs, transportation, and more.

In Camas, Proposition 4 will raise $17.1 million in 2022 and $18.2 million in 2024 with an “estimated” levy rate of $2.50 per $1,000 of assessed value. Proposition 5 is primarily a technology levy that will raise $3.7 million in 2022 with an “estimated” rate of $0.54 per $1,000 of assessed value. These funds will make up 20 percent of school funding according to CSD literature.

The school district website reports the need is because of “flattening revenues driven by the state funding formula. Furthermore, “annual expenditure increases of approximately 9 percent annually over the past four years, driven by growth in personnel costs,” meaning employee pay raises are driving an unsustainable budget, unless additional taxpayer money is received.

The history of McCleary

The McCleary case began more than a decade ago. In 2007, the McCleary family of Chimacum, sued the state “for not meeting its constitutional obligation to amply fund a uniform system of education.”

They argued that the use of local property levies created a gap between state funding and the actual cost of operating schools, resulting in a system that favors rich districts and placed an unfair burden on local taxpayers.

While the case worked its way through the courts, the legislature approved legislation in 2009 that incorporated an updated definition of “basic education,” including all-day kindergarten and no more than 17 students per certificated staff in grades K-3.

In the years following the court decision, the state legislature has doubled their funding of K-12 education. One news report said “the state solved the McCleary problem by reducing local districts’ reliance on local levies.” Education is now the single largest expenditure in the state budget, representing just over half the state General Fund budget allocation.

A “per pupil model” of funding graphic shows the legislature’s commitment. State allocations grew from $13,549 in the 2011-13 budget to $27,305 in the 2019-21 budget. (These are 2-year budgets and allocations). The promise was that taxpayers would see relief in local property tax levies which were an unfair burden, as the state increased funding.

Elected representatives told their constituents they could expect “long term tax relief.” Sen. Ann Rivers (Republican, 18th District) highlighted a 30-percent rebate in property taxes at an April 2018 town hall event. The drop would occur in 2019, though she said the relief doesn’t go as far or come as fast as Republicans had hoped. Rivers was one of four legislators to craft the final McCleary “solution.”

Teachers strike

In the summer of 2018, teachers around the state went on strike demanding significant pay raises. Some were demanding as much as 25 to 35 percent. Teacher strikes are illegal in Washington, yet the Attorney General refused to file lawsuits or prosecute the Washington Education Association (WEA).

In March 2018, the Washington Policy Center shared the following:

“Recently WEA union president Kim Mead gleefully announced that public school employees will be getting double-digit pay raises.

“Mead admits teachers just received a round of pay raises, but she tells her members more money is coming. She says school employees can expect raises as high as 37 percent. The public sector raises come at a time when many taxpaying working families have seen flat or declining incomes in recent years.”

In August, the WEA touted “More big pay raises for Washington educators – and more strikes.” They shared their success: “in Shoreline, as reported last week, the top salary is now more than $120,000.”

“One group that has been largely silent as this debate boils over, are the lawmakers who crafted and passed the McCleary funding fix” stated Clark County Today’s news report at the time. Sen. John Braun (Republican, 20th District) did fight to enforce the law.

Braun sent a letter to Gov. Jay Inslee, Attorney General Bob Ferguson, and Superintendent of Schools Chris Reykdal in August insisting that they enforce state laws prohibiting a teacher strike to force teachers to go to work. Braun says he never heard back from any of those elected officials.

“I’m disappointed that I have received no response from them, but more importantly students, parents and teachers have heard nothing but silence,” Braun said at the time.

Rep. Vicki Kraft, a 17th District Republican, voted in favor of the final (2018) McCleary funding bill. She sent a brief comment via text. “The State Legislature voted to increase K-12 funding $8.1B during the past two sessions and these funds will be fully implemented by 2021,” she wrote. “As a result, K-12 funding now makes up 52% of the State’s General Fund Budget. Given these facts, it’s very unfortunate to see these strikes taking place.”

Camas educators voted to strike, but reached an agreement with the school board. They had previously agreed to a three-year contract in Oct. 2017, yet demanded to reopen their contract less than a year later. The school board ultimately agreed to amend the contract providing an average 12.5 percent increase in compensation.

Included in the agreement was a new “longevity stipend” for the most senior teachers. Superintendent Jeff Snell said that it was clear that a competitive top end salary was a priority for the Camas Education Association (CEA) and they had to be creative in finding a way to get there. The longevity mentor stipend is a different way to provide compensation that is not applied to the entire salary schedule according to Snell. The highest paid teachers got this added bonus.

The new salary range for the 2018-19 school year became $50,727 to $97,529, and from $52,868 to $100,110 for the 2019-2020 school year. “We wanted to capture as much of that McCleary money in the first year,” Shelley Houle, president of the Camas Education Association said at the time. “That’s when the influx of money is coming in.”

The union’s lead negotiator Mark Gardner believed that CSD couldn’t get to six figures. He insisted the district was “over-staffed,” meaning they exceed state standards for full-time employees.

Having more employees than the state says is needed, and paying them some of the highest wages in the state leads to budget problems.

Layoffs projected

At the time, Snell and the school board knew the agreement was unsustainable. At the CSD school board budget review session on Aug. 13, budget forecasts revealed a 3.8 percent layoff projection, based on a pay raise of 3.1 percent, not the 9-12 percent the board agreed to two weeks later in the amended contract.

Snell said the new two-year agreement gives the district time to come up with solutions, however, he adds “we have a tough road ahead under the new funding model.”

Some citizens have asked why Snell didn’t demand the union work according to the promise they’d made less than a year earlier. Why would a school board agree to a contract that leads to layoffs? Why would junior teachers vote in favor of a contract that projected their layoffs?

The current CSD Executive Summary shares today’s reality:

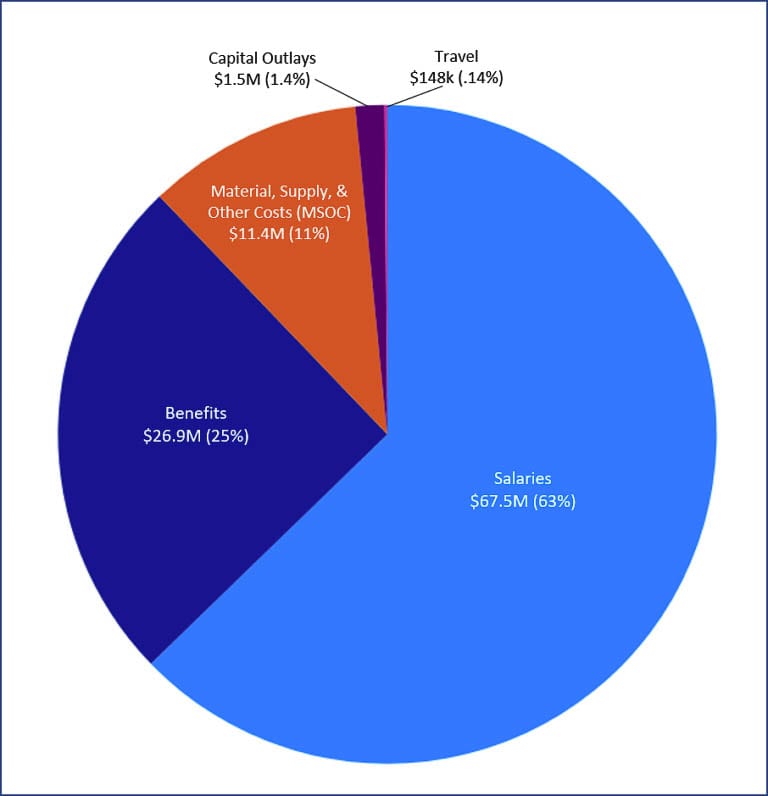

“Over five years, salary and benefit costs have increased 51 percent with a 14 percent increase in full-time employee equivalents (FTE). The expenditure increase has aligned with revenue increases in the past and were largely driven by increases in salary and benefit cost, which represent about 88 percent of total district costs. Current expenditure growth trends outpaces projected state revenue growth. Future realignment of expenditures to better match the revenue curve will be necessary for a sustainable model moving forward.”

CSD officials conclude: “the challenge will be to control expenditure growth going forward, as a continued annual expenditure growth of over 9 percent is not sustainable.” The district was unable to control expenditure growth over the previous five years, when agreeing to the 51 percent compensation increases.

Seniors losing homes

At a Jan. 2019 town hall event, state representatives spoke about spending the prior three legislative sessions addressing K-12 education funding due to McCleary. Sen. Rivers responded to a citizen question about “when are we going to get our property tax relief locally?”

Rivers mentioned that Democrats had recaptured control of the Senate, while also having the House and the Governor’s mansion. “They erased about 90% of the entire McCleary bill,’’ Rivers said. She predicted the legislature would be addressing education funding again within three years.

“We put $11 billion more into the education system with the caveat that there could be no increase in (union) contracts that were not open and negotiated,” Rivers said. That meant the CEA and other districts could not reopen their contract; yet that is exactly what happened around the state.

“I was quoted in the newspapers saying it was like dragging a donut donut through a fat farm,” she said. “Everyone saw the money and jumped in and wanted their piece. We saw these amazing spikes across the state in teacher pay.”

“They wanted it all, they wanted it now, and they took it.”

Rivers said she was concerned about the property tax issue in Camas. “I’m most sensitive to Camas, because the most seniors lost their homes (were) in Camas in my district. It was the seniors who lost their homes because they can no longer afford to pay the taxes.”

Three months later, Washington state was shut down by the governor due to COVID-19. Current enrollment has dropped from what was anticipated in the 2020-21 CSD budget. In early January, officials reported 464 students had withdrawn from the schools.

Camas voters have received several communications in the mail. Each points to a maximum total school levy rate of $4.77 per $1,000 of assessed value. Voters should understand that the assessed value of their home changes each year and therefore the total taxes they pay on any “voter approved” assessments will vary.

The two levies are seeking voter approval for $20.89 million in 2022, $21.51 million in 2023, and $22.16 million in 2024. The larger is the Educational Programs and Operations (EP&O) levy which provides about 20 percent of the district’s budget. The smaller is the Technology, Health and Safety levy. The later assessment will nearly double from 28 cents to 54 cents. The EP&O levy assessment will remain the same at $2.50 per thousand of assessed value. It had been as high as $2.97 in 2018 and as low as $1.50 in 2019.

Clark County Today will follow this report with an in-depth look at CSD’s actual income and expenditures during the McCleary era.