Explosion in project costs, funding and Coast Guard remain obstacles

John Ley

for Clark County Today

Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg was in Clark County again visiting the Interstate Bridge replacement project for the second time in seven months. In his previous visit he doled out $40 million in federal funds to Washougal. This visit he told citizens “because funding is in place, it’s going to happen.”

Governors Jay Inslee and Tina Kotek joined a parade of local officials on the Vancouver waterfront and on the bridge to promote the project that will include a 3-mile, $2 billion MAX light rail extension. Interstate Bridge Replacement program (IBR) Administrator Greg Johnson has told the community the $5 billion to $7.5 billion price tag will go up, but would not provide specifics during the Buttigieg visit.

“Right now, it’s too large and too complex for traditional funding to work,” Buttigieg said. He might look 60 miles east at Hood River. The two states are building a taller, less “complex” bridge at a wider crossing of the Columbia River for $520 million.

To date, the federal government has allocated $601 million for the partially designed project. Washington state has allocated $1.1 billion. Oregon has allocated $250 million and promised another $750 million.

Today, (Valentine’s Day), half the bridge structure turns 107 years old. The northbound structure received an upgrade in 1958, after the southbound structure was built. Seismic concerns are listed as a major reason for replacing the bridges, yet both Oregon and Washington departments of transportation list the bridges as being safe. They are just not built to current freeway and seismic standards.

Some citizens are suggesting the bridges be repurposed as a local connection between Vancouver and Hayden Island rather than be destroyed. Many believe an immersed tube tunnel would better serve the region and avoid restrictions for maritime traffic.

The financial realities of the replacement project are far from settled. Issue number one is the cost. After Governors Jay Inslee and Kate Brown signed their memorandum in November 2019 restarting the program, the cost was updated a year later to a range of $3.2 billion to $4.8 billion by IBR staff. That included inflation in the out years, and also included light rail.

Two years later (Dec. 2022), the price jumped to a range of $5 billion to $7.5 billion, with Johnson regularly touting a “likely” $6 billion cost. Yet last fall, Johnson told Oregon and Washington legislators that the cost was going up again saying “the replacement project is falling victim to a continuing creep of costs.”

Portland economist Joe Cortright has estimated the “new” price tag will be in the $7 billion to $9 billion range. “The use of lowballed construction cost estimates to sell highway megaprojects is part of a consistent pattern of “strategic misrepresentation,” Cortright said. “It’s the old bait-and-switch: get the customer to commit to buying something with a falsely low price, and then raise the price later, when it’s too late to do anything about it.”

The IBR team reports they expect $2 billion in funding from the two states, $2.5 billion from both the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, and $1.2 billion to $1.5 billion in tolling bond funds. That is potentially $6 billion to pay for a project they now admit will cost more.

But Oregon Governor Kotek is not happy with how the state legislature funded its share of the project. The lawmakers allocated $250 million from the 2023-24 general fund budget, and promised the $750 million balance would come in three $250 million allocations in the ensuing three biennial budgets through 2030. Kotek wants to preserve those general fund revenues for other things, and has asked the legislature to find another funding source for the IOU currently in place.

Separately, Oregon citizens are in an uproar over tolling, especially in Clackamas County. A group is collecting signatures on IP-4 which would guarantee a Vote Before Tolls can be put on any Oregon highway. The initiative is retroactive to 2017 and includes the Interstate Bridge. If they collect 200,000 signatures by the end of June, IP-4 will be on the November ballot, putting at least $1.2 billion of IBR funding at risk.

The major cost components of the IBR are $2 billion for the 3-mile MAX light rail extension into Vancouver, $1.6 billion for interchanges in Oregon, $1.5 billion for interchanges in Washington, and $500 million for the bridge itself.

If the Cortright $9 billion estimate is correct, there is a $3 billion funding shortfall on the project. If IP-4 is approved by voters in Oregon, there would be up to a $4.5 billion shortfall.

It is unlikely the Oregon legislature will pony up additional funds, as they already have roughly a $3 billion funding shortfall on numerous other transportation projects. These include the “paused” $2 billion Rose Quarter, the I-205 Abernethy Bridge, the Tualatin River Bridge, and the Wilsonville Boone Bridge.

A press release said Buttigieg “met with local leaders to learn about the urgency of the massive infrastructure project and how it will create economic opportunity, reduce traffic congestion, improve public transit, and strengthen national supply chains.” Many citizens know the project will not reduce traffic congestion or save them travel time, the one thing people truly want the project to fix.

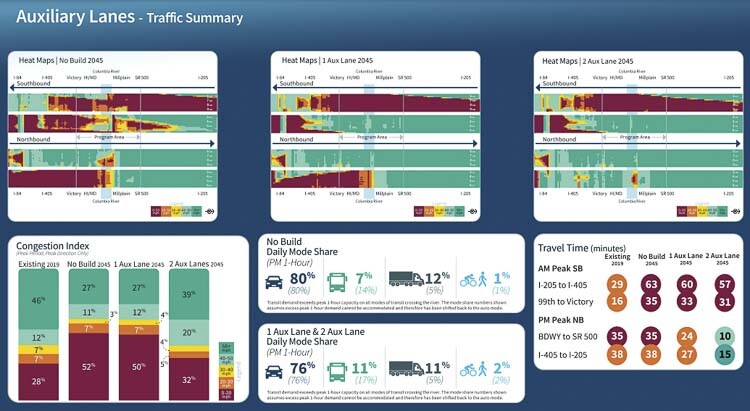

Buttigieg addressed criticism from the left that this project expands the freeway. He said he doesn’t automatically assume adding more lanes is the answer. The IBR is replacing a congested three-lane bridge with another three-lane bridge. They report travel times from Salmon Creek to Portland’s Fremont Bridge will double to 60 minutes by 2045. They additionally expect that half of rush hour traffic will be going zero to 20 miles per hour in 2045.

“But it’s also the case that congestion on the bridge is a problem,” he said. “We don’t go into this one-dimensional. The multimodal component is one of the things that is so compelling about the project.” Yet the $7.5 billion proposal doesn’t reduce traffic congestion, which Buttigieg either doesn’t know about or chooses to ignore. Transit ridership remains well below pre pandemic levels both locally and nationally.

The choice of light rail for the “multimodal component” is the cause of many of the project’s problems. Besides being the most expensive piece of the funding puzzle, it also is causing the bridge design to be “too low” for the US Coast Guard approval. The recent revelation of the Vancouver Waterfront MAX light rail station being at least 75 feet in the air seems to ensure people won’t use it, not to mention the eminent domain taking of a five-year-old, six-story building.

The Coast Guard is demanding a bridge with “at least” the current 178 feet of clearance for marine traffic. They have veto power over the project and would prefer a bridge with unlimited clearance. The IBR has added a movable span design option, but few believe this is under serious consideration.

What has caused prices of transportation projects to explode out of control? Poor management by DOTs is one problem. Politics is another. The federal government throwing an unprecedented $1.2 trillion via the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act (IIJA) has also played a key role.

A northern California BART extension project jumped 31 percent last fall, adding nearly $3 billion to the cost estimate. “New cost estimates for the BART extension fall squarely in line with what we are seeing across the nation,” said Peter Rogoff, former U.S. Department of Transportation Under Secretary and Federal Transit Administrator.

In November 2021, President Biden signed the $1.2 trillion IIJA. Oregon and Washington were expected to receive $14 billion federal dollars, in addition to funds for projects like the IBR.

“Construction costs rose almost 3 percent during the first quarter of 2023, and contractors have seen a 50 percent increase over the past two years,” according to one news report. “Over the 10 quarters, highway construction costs grew 53.8 percent,” reported the Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

“Inflation Has Contractors Taking Pass On Federally-Funded Transportation Projects” reads one headline. It’s likely the huge IIJA funds triggered the significant cost inflation.

The Biden administration applauded the $273 billion increase in highway spending that was a major chunk of IIJA. “Unfortunately, it is increasingly likely that inflation will wipe out the entirety of that funding increase,” believes Mark Scribner of the Reason Foundation. “New Buy America requirements on manufactured products will make this problem even worse.”

The bottom line to all this is the IBR is far from fully funded, which would obviously make it far from “a done deal,’’ as Buttigieg suggested. There is no final design, the Coast Guard stands firmly in the way of approval, and exploding costs remain huge obstacles. Then there’s IP-4 as voters are expected to reject tolling.

Also read:

- Expect delays on northbound I-5 near Ridgefield through May 9Northbound I-5 travelers near Ridgefield should expect delays through May 9 as crews work on improvements at the Exit 14 off-ramp to support future development.

- 6-cent gas tax hike central to new transportation deal in WA LegislatureA proposed 6-cent gas tax hike is central to a transportation funding deal under negotiation in the Washington Legislature, aimed at raising $3.2 billion over six years.

- Letter: C-TRAN Board improper meeting conductCamas resident Rick Vermeers criticizes the C-TRAN Board for misusing parliamentary procedure during a controversial vote on light rail.

- Opinion: TriMet’s ‘fiscal cliff’ a caution for Clark County taxpayersRep. John Ley warns that Portland’s financially troubled TriMet transit system could pose major risks to Clark County taxpayers as the I-5 Bridge replacement moves forward.

- Travel Advisory: Expect daytime delays on northbound I-5 near Woodland for guardrail repairs, April 18WSDOT will close the left lane of northbound I-5 near Woodland on Friday, April 18, to repair guardrail and improve driver safety.