The district will dip into emergency funding to offer a lower tax rate in the first year of the four-year maintenance and operations levy

BATTLE GROUND — Next Tuesday’s special election will mark four years since Battle Ground Public Schools asked voters to approve a replacement Maintenance and Operations Levy.

That levy, which carried a rate of $3.66 per $1,000 of assessed value in its first year, passed narrowly, with 53.69 percent of the vote.

This time, the district is asking for a rate of $1.95 per $1,000, rising to an estimated $2.20 in the final three years of the levy.

To hit that lower rate in 2022, the Battle Ground School Board voted to dip into the district’s emergency fund balance to make up the shortfall.

“There are things we want to make sure that we maintain to help our students be successful,” says Superintendent Mark Ross, who is retiring at the end of June. “But on the other hand, [the board] did recognize that there are people out there that really could use some help economically.”

The replacement levy, if approved on Feb. 9, is projected to bring in around $20 million less than the expiring levy.

The district estimates it would bring in $24.9 million next year (with the balance made up through rainy day funds), $29.2 million in 2023, $30.4 million in 2024, and $31.6 million in the fourth year.

Should new construction and property values continue to grow at or near their current pace, the district is fairly confident the tax rate would be less than projected.

“We’re very conservative when we set the amount of what we estimate that the assessed values would be,” said Ross. “We’re estimating a 5 percent growth, and we’ve always been low on that estimation.”

All else being equal, approving a replacement levy with a starting price 22 percent lower than the $2.50 per thousand people were paying last year, and 53 percent less than what voters approved in 2017 would seem like an easy sell.

But a lot has changed in the last four years.

Not the least of which was the state legislature’s decision in 2018 to cap local levies at $1.50 per thousand, while raising the statewide property tax levy for basic education to a current rate of $2.70 per thousand.

That decision was the result of an 11 year court battle that ended with a loss in the state Supreme Court, which ruled the state was failing its duty to fully fund basic education.

That lawsuit alleged the state had allowed too much of the burden for augmenting teacher salaries to fall on local districts, creating disparities in which property-rich districts could afford to pay teachers more, leading to a competitive disadvantage for other districts.

The legislature returned in 2019, approving an increase for the local levy lid to $2.50 per thousand, or $2,500 per student, whichever was less, in an attempt to allow property-poor districts to further level the playing field.

While most Clark County districts had already passed replacement levies at the $1.50 rate, Battle Ground was still in the midst of their four-year levy. The school board voted unanimously to take advantage of the new, higher rate.

“The board felt that that was an opportunity to go to $2.50 and get an amount where we were able to spend some things on capital improvement, safety projects, and technology,” said Ross, “and put that in one levy and not go to the supplemental levies.”

That decision came on the heels of yet another narrow defeat in 2018 of a $225 million building bond, which fell about 7 percentage points short of the 60 percent needed to pass.

Instead of going back to voters the next year with another building bond, the levy lid lift presented the option to accomplish some of the building bond’s goals without the need for voter approval.

“We didn’t want to run a 30 year bond and have people pay for it over 30 years,” says Ross. “So that gave us the ability to do some of those facility improvements that we may not have been able to do otherwise.”

What do local levies pay for?

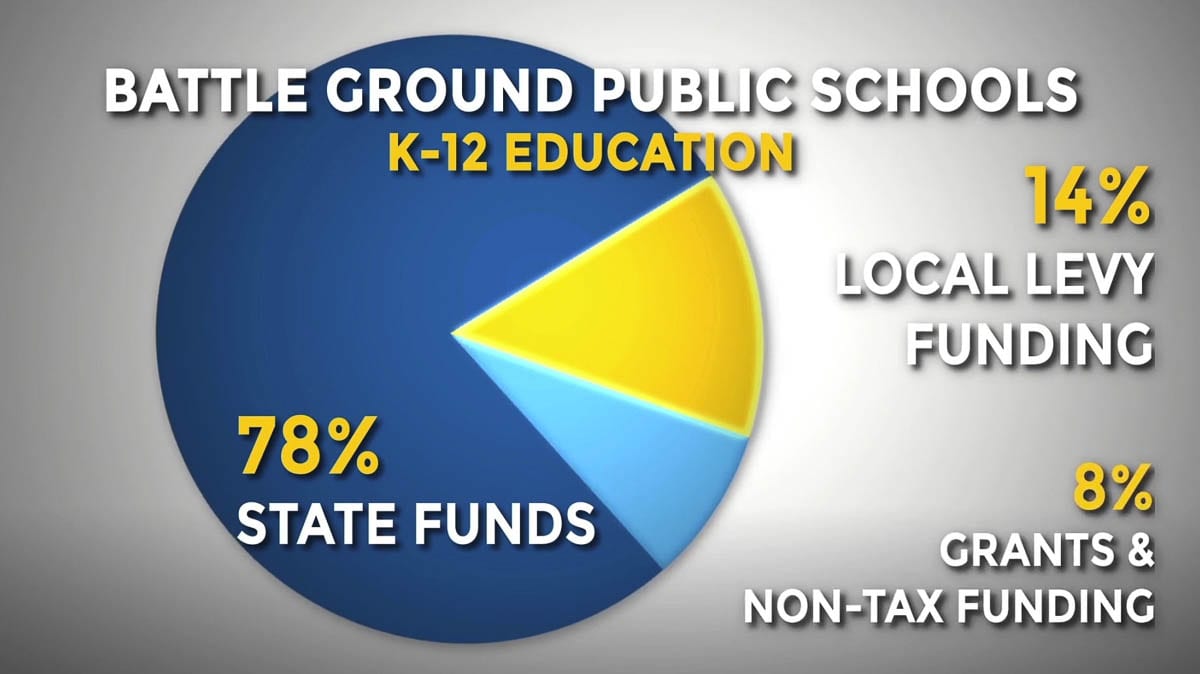

Historically, local levies were intended as a way for school districts to provide additional programs and staffing not covered in the state’s prototypical basic education model.

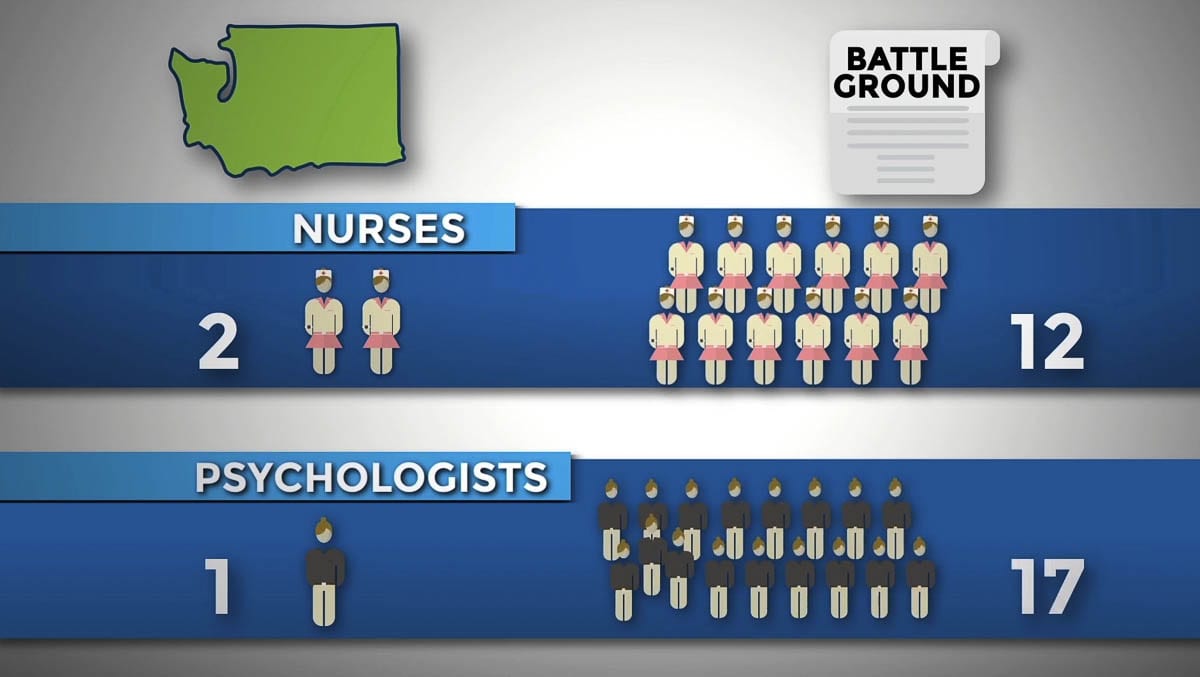

That prototypical model provides state funding for 1.74 nurses to cover all 18 schools in the Battle Ground school district, 2.04 security guards, and 0.34 psychologists.

In 2020-21, the existing Battle Ground school levy will provide over $14 million for education supports, such as 10 additional school nurses, 16 school psychologists, and six more security guards. $5 million will be used to provide building maintenance and operations, $4.15 million for sports, social-emotional learning, advanced placement programs, as well as textbooks and curriculum. Another $3.6 million goes to special education services, and $1.9 million for technology, security, and communications.

“We think we’ve done a great job with purchasing newer technology and updating our curriculum for our students, and providing health services with the nurses,” says Ross. “And it’s important to note that this is a replacement, to just maintain and be consistent with those things that the state doesn’t fund, which we think we need to help our students be successful.”

Worst case scenario

Should the levy fail to gain the simple majority necessary to pass next week, the school board could elect to re-run it in either August or November.

If it ends up not passing now or then, the district estimates they would face a $14 million budget hole next school year, with more cuts to follow the year after that.

(The district would still receive local levy dollars for the first part of the 2021-22 school year, since they operate on an annual budget cycle)

The full effect of a failed replacement levy wouldn’t likely be known until later this year. Like most districts, Battle Ground is still trying to determine the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their bottom line.

While the district has already received some funding through the CARES Act passed in March, the money was mostly used to buy masks, hand sanitizer, plexiglass, and upgraded technology for teachers, including computer systems with integrated cameras for remote learning.

Barring action by the legislature, the district could face revenue losses in the millions or tens of millions of dollars, due to enrollment declines and lost transportation funding.

At last count, enrollment in the district is down about 1,000 students from this time last year, though Ross said there are some indications many of those students may return as the transition to in-person learning resumes.

“Already this month, we’ve seen some of our primary students come back,” says Ross.

The district also announced Wednesday that with COVID-19 case rates in the county dipping below 350 per 100,000 people this week, middle school students will be able to return to hybrid learning starting Feb. 22, with in-person classes two days a week.

At the moment, Ross says they feel cautiously optimistic that their conservative approach to requesting local funding will pay off.

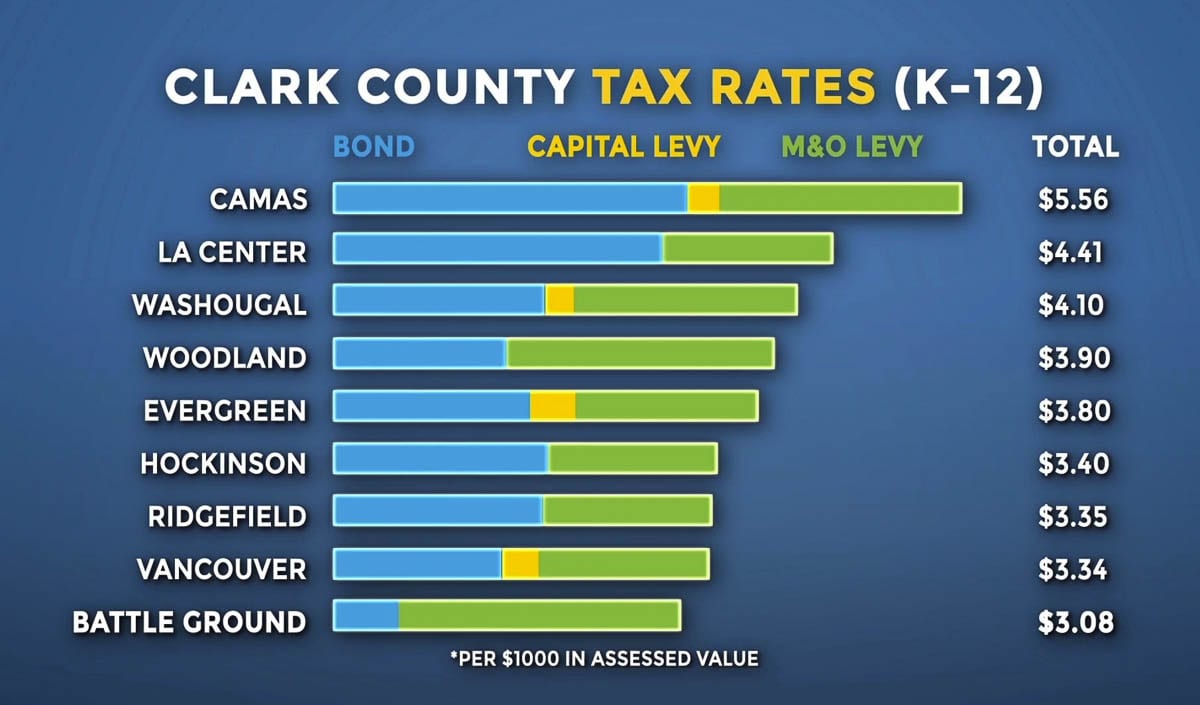

Last year, Battle Ground’s overall school tax rate was still $0.26 lower than Vancouver Public Schools, and nearly $2.50 per $1,000 less than Camas, which is also voting on a replacement levy next week that would further increase their rate next year.

“We’re very hopeful, and hopefully people understand that this is a four year levy,” said Ross. “Hopefully, COVID will end sometime in the near future, and this will keep us on track.”

One final note: Starting in 2022, the state will switch from a fixed rate system for school funding to a budget-based one. That means the state will collect property taxes sufficient to reach an approved budget amount, with a maximum levy rate of $3.60 per $1,000 of assessed value (though the actual amount will likely be lower to start).

In the years that follow, tax increases would be tied to economic growth or inflation, capped at the lesser of the one percent growth factor, or inflation.