Plenty of people attending a weekend open house at the Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver wanted to know more about the Kilauea eruption

VANCOUVER — Hundreds of people swarmed the Cascades Volcano Observatory offices in east Vancouver over the weekend. The open house, held by the US Geological Survey, happens every two or three years and is always popular, but this year people were buzzing about the ongoing eruption of the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii.

“It’s likely that the activity at Kilauea has really brought volcanos back into focus for people here in the Cascade range,” said Carolyn Driedger, a hydrologist and outreach coordinator for the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory.

The Pacific Northwest, of course, has its own tragic history with volcanoes. In 1980, Mount St. Helens erupted in one of the most famous natural disasters in U.S. history. The eruption caused billions of dollars in damage, and left 57 people dead. The 38th anniversary of the Mount St. Helens eruption is this Friday, which is why May is Volcano Preparedness Month in Washington state.

“A new generation of people lives here now,” says Driedger, “and some people forget that this is an active volcano range. We will have eruptions here again, we can expect that, and we all need to be ready.”

The number one question people ask, says Driedger, is which volcano around us is likely to erupt next. While there are many active volcanoes along the Cascades, including Mount Hood and Mount Rainier, most scientists believe the last volcano to blow its top around here is still most likely to be the next to go.

“There’s a great Japanese proverb that says, ‘disaster will happen the moment that the memory of the previous one has been lost’, says Driedger. “And, so it’s really important for us here in the Cascade Range to remember the losses in 1980 at Mount St. Helens, and never forget that people lost lives, and it was a time of real hardship and heartache for a lot of people. And since we don’t know when the next eruption will happen, we need to be ready.”

One of the good things to come out of the eruption happening on the island of Hawaii may be an increase in our ability to prepare for the next eruption here. The Cascades Volcano Observatory is a partner with the one in Hawaii, and seismologist Weston Thelen was actually there. He left just a day before the actual eruption began.

“We saw high lava lake levels, we saw endogenous growth, that’s growth within Pu’u (O’o crater) that was inflating very rapidly,” says Thelen, “so we were discussing as a group what the outcome was going to be. Certainly something happening outside of Pu’u O’o was a reasonable outcome, but obviously being able to pinpoint that it was going to happen in the lower east rift was not something that we really would have been able to forecast, even knowing what we know now.”

While Hawaii’s youngest volcano has been erupting almost constantly since 1983, increased build up of the Pu’u O’o crater began in mid-March. On April 30, the crater floor collapsed, sending lava toward the residential Puna District. Things really kicked off May 3 with a 5.0 magnitude earthquake, then a 6.9 magnitude the next day, which caused the crater to collapse, and fissures to open in nearby Leilani Estates. Since then some 18 fissures have opened up in the area. Over 2,000 people have been evacuated due to the lava and dangerous levels of sulfur dioxide being released into the air. Some two dozen homes have been destroyed, but so far no human lives have been lost.

But the worst may not be over yet.

“We’ve got a falling lava lake, which has fallen over a thousand feet now,” says Thelen, “and if we get some magma interacting with the water table, we have the potential for explosions.” Those explosions could send ash and rocks hundreds of feet into the air, creating hazards for people still near the mountain.

Learning lessons

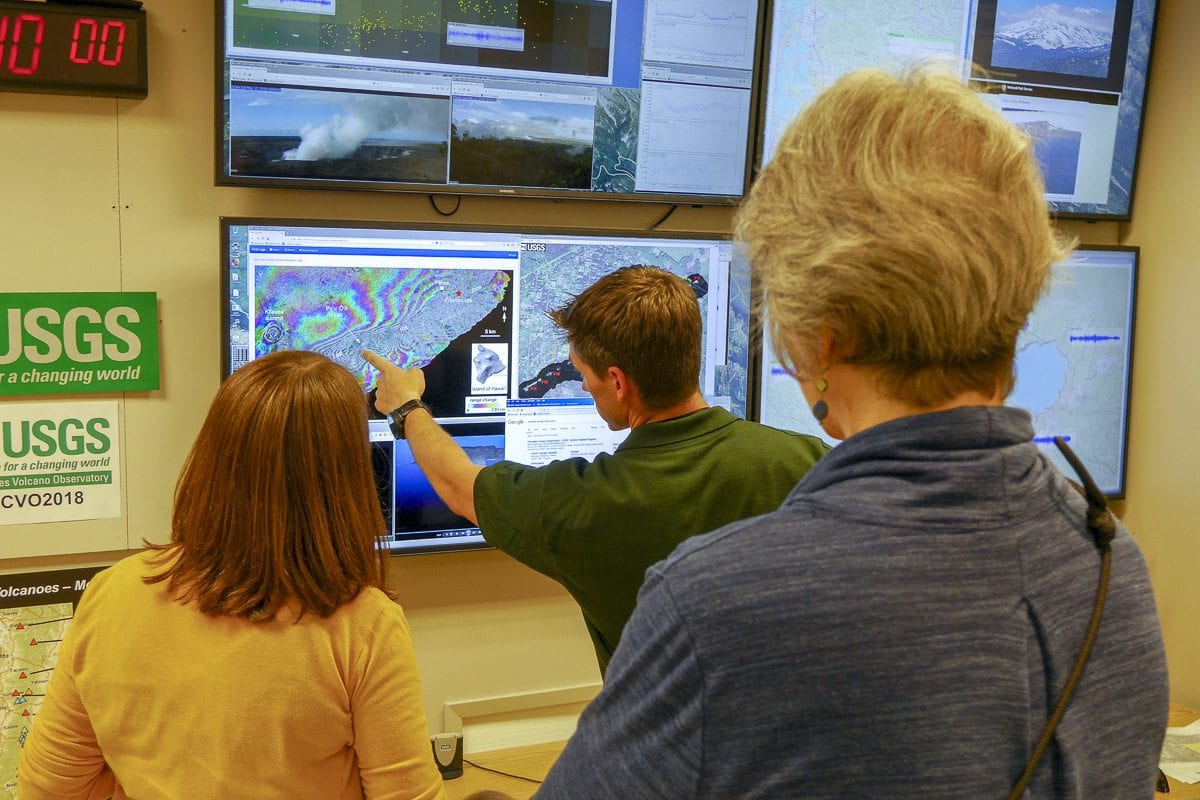

Scientists are already gleaning massive amounts of information from what’s happening at Kilauea. Behind Thelen, a wall of computer monitors displays real-time data being recorded on and around the erupting mountain, from seismic activity to lava flows, gas levels, and more. It actually allows scientists in Vancouver to monitor what’s happening there, while Hawaiian scientists catch a little sleep.

While Kilauea is much different than the one in our own backyard, there are lessons to be gleaned. “Even though they’re vastly different volcanoes, the process of magma and gas moving through the crust is the same process that leads to earthquakes underneath Cascade volcanoes,” says Thelen, “and so we can apply those lessons back to the Cascades.”

New studies done in the past 5-7 years have helped geologists better understand the type of magma system underneath Mount St. Helens. While it’s unlikely an eruption there would cause fissures like the ones happening in Hawaii, a dome volcano eruption is often much quicker and more violent. There are volcanoes in central Oregon, such as the Belknap Crater, that are similar to Kilauea, but there has been no active eruption there for an estimated 1,300 years.

Open house

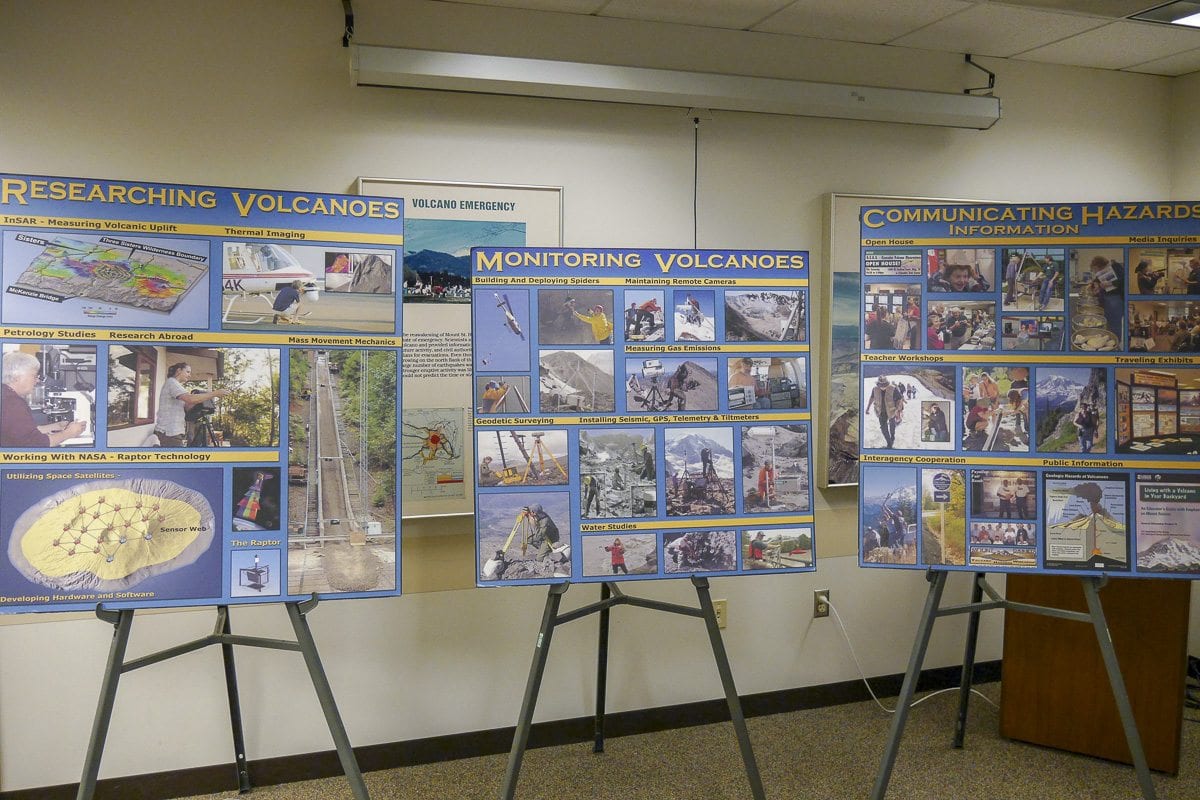

Meanwhile, there was an obvious buzz of excitement in the air as an estimated 1,200 people checked out the high tech equipment and methods scientists are using to understand what’s happening to the earth beneath our feet; From sensors that can detect minute movement in the earth’s crust, to cameras and even drones that can fly above a crater. In an outside lot kids helped measure how far “debris” from a liquid nitrogen-fueled TrashCano flew, and how loud the explosion was. Others brought their own rocks so that USGS geologists could tell them where it came from, and help them understand a bit of its history.

The tragedy of the Mount St. Helens eruption nearly 38 years ago, in many ways, gave birth to the modern study of volcanoes. We’re still a ways off from understanding exactly what causes an eruption to begin, or when it might happen again, but the one happening in Hawaii, while it represents a dangerous situation, and a tragedy for many, is also a chance for another leap forward in our understanding of this dangerous world we live in.