IBR proposal is less than half the length and one third lower than the Baltimore, but possibly 20 times the cost

John Ley

for Clark County Today

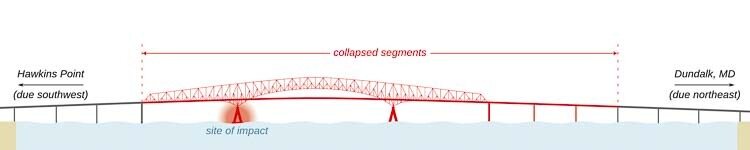

The accident and tragedy of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse has brought national attention to bridges and maritime safety. The bridge is reported to have carried 30,000 vehicles per day and a significant amount of freight on I-695. As government authorities seek to learn what happened while also clearing the wreckage, efforts are underway to replace it.

The Epoch Times reports this is the third accident involving a mega-ship this year. “Baltimore’s Key Bridge joins the Lixin Sha Bridge in southern China’s Guangzhou province and the Zárate-Brazo Largo Bridge on the Parana River in Argentina as 2024 victims of mega-ship allisions — a new word to learn when a massive ship runs over a stationary victim — in confined waters.”

Replacing the bridge could cost at least $400 million and take 18 months, reports the Associated Press. An engineering professor at George Washington University said the project could take as little as 18 months to two years. Others are more skeptical, indicating five to six years.

It all depends on getting an approved design, and how swiftly government officials can clear the bureaucracy of permit approvals and awarding contracts. The 8-lane I-35 bridge in Minneapolis was replaced with a 10-lane bridge in 13 months for $234 million following the 2007 accident.

President Joe Biden pledged Tuesday that the federal government would cover the massive cost of rebuilding the bridge, but there was immediate bipartisan pushback. Initial estimates vary widely, between $400 million and $2 billion in news reports. Maryland transportation officials will need to evaluate whether to build a larger roadway that can carry more vehicles, or whether to raise the bridge’s height above the water to accommodate larger ships passing under it, reported the NY Times.

Many ports will soon be backwaters, the 54-member nation International Transport Forum’s 2015 “Impact of Mega-Ships” report predicted. They are fighting to be able to serve even larger container ships or risk becoming irrelevant, a fear some in Baltimore have now that container ship traffic is diverting to New York/New Jersey, Norfolk, Savannah, Charleston and other east coast ports.

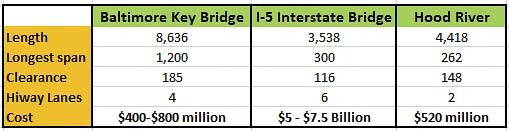

Yet all this calls into question many facets of the I-5 Bridge Replacement project. Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBR) Administrator Greg Johnson and his team are predicting a decade-long construction process to build a bridge 62-feet lower than the current structures, which will likely require over $100 million in mitigation costs to four up river firms. The $7.5-billion price tag is potentially 20 times the Key Bridge replacement cost. It will be going up, with details to be released later this summer.

The 4-lane steel bridge in Baltimore is 8,636 feet long, providing 185 feet of clearance for maritime vessels, with its longest span of 1,200 feet. It was built over five years, opening in 1977, serving as a second transportation corridor over the Baltimore harbor. The Port of Baltimore is one of the busiest in the nation.

The 6-lane I-5 bridge is 3,538 feet long and provides 72 feet of clearance when closed and 178 feet when the lift span is open for marine vessels. The current longest span is 531 feet and the IBR team is proposing 300 feet of horizontal clearance in the Locally Preferred Alternative (LPA). It carries close to 140,000 vehicles on an average day and reached its design capacity in the mid 1990s according to transportation officials.

For comparison, the current Hood River Bridge is 4,418 feet long and provides 148 feet of clearance for marine vessels. The proposed replacement is projected to cost $520 million, offers 450 feet of horizontal clearance, up from 246 feet, and 80 feet of vertical clearance. It will eliminate the lift span and replace a 2-lane structure with a 2-lane bridge.

The current proposal for the IBR project has met with stiff opposition from the Coast Guard.

They are demanding a bridge with at least 178 feet of verticle clearance for marine vessels, and would prefer “unlimited” clearance, indicating either a tunnel or a bascule bridge, like Portland’s Morrison or Burnside bridges. Construction will prove particularly troubling for many current Columbia River users, requiring steering tug boats for safety. Horizontal clearance will be reduced to about 120 feet.

The constantly rising price tag raises questions on what the people are paying for and what are the benefits. Replacing an over-congested 3-lane bridge with another 3-lane bridge that will be tolled during construction, has raised the ire of significant numbers of people. Traffic congestion is predicted to get worse, with travel times doubling by 2045 when going from Salmon Creek to the Fremont Bridge.

With $2 billion for the light rail transit component alone, Clark County Today Editor Ken Vance notes that MAX could be removed from the project and eliminate the need for tolls. C-TRAN buses currently carry only about 1,000 people a day over both I-5 and I-205 bridges. Express Routes crossing the I-5 bridge saw an average of 523 daily boardings in 2022.

The current $5 billion to $7.5 billion budget for the Interstate Bridge replacement allocates $500 million to replace the bridge. There is $1 billion to $1.5 billion in Washington roadway costs and $1 billion to $1.6 billion for Oregon roadway costs. The price of the 3-mile MAX light rail extension is $1.3 billion to $2 billion.

Tying back to the replacement of the Key Bridge potentially costing $400 million to $800 million, focusing on the $500 million portion of the IBR cost projection zeroes in on just the bridge itself.

The August 2007 collapse of the I-35 bridge in Minneapolis serves as another example. The 8-lane interstate bridge was replaced in just 13 months with a 10-lane bridge after 11 months of construction. The $234 million replacement was finished three months ahead of schedule, or about $350 million in today’s dollars.

Figg Engineering designed the replacement bridge in Minneapolis. After the failed Columbia River Crossing (CRC) debate, Figg offered to sign a fixed-price contract to build a new bridge in east Clark County at 192nd Ave for $860 million. They estimated a bridge connecting Troutdale with Camas where the river is narrower could be done for $800 million.

Traffic considerations

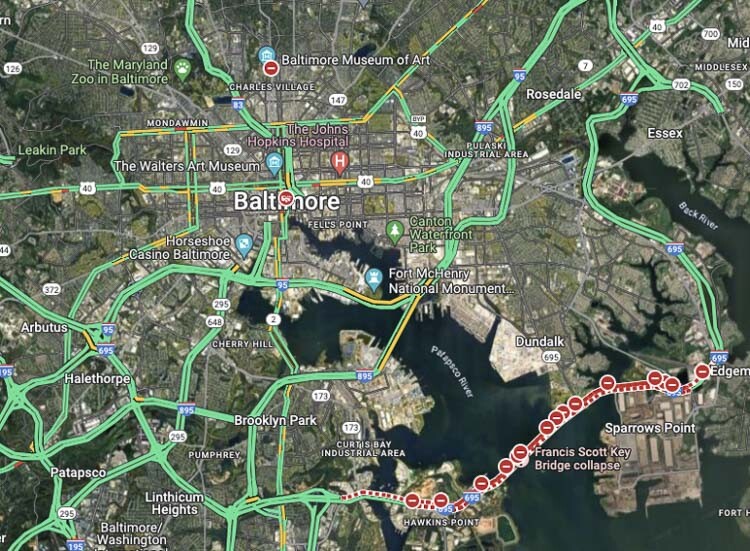

The loss of the Key Bridge may cause many to wonder where did those 30,000 vehicles go and how did it impact Baltimore’s traffic? Portland economist Joe Cortright noted there were no problems, showing all major routes “green” two days later. How can that be?

A quick look reveals multiple major highways and bypass arterials in the Baltimore area that provide alternatives and redundancy for vehicle traffic. I-95 has three bypasses; I-195, I-695 and I-895. Then there’s I-97 and US 40, US 1 and a host of state highways. The map literally looks like a spiderweb, full of bypasses around the city.

Local Baltimore officials predicted a “traffic nightmare after bridge collapse”, which apparently didn’t materialize. Having multiple alternatives for vehicles to adjust to using apparently saved the day for the region.

Here in Portland, the city has a dozen bridges over the Willamette River. Each bridge serves a unique subset of travelers while providing redundancy and options when there are accidents or bridge openings for river traffic. Yet there are only two bridges over the Columbia River, both of which experience congestion a majority of the day.

For the better part of a decade, the Portland metropolitan area has ranged between the 10th and 12th worst congested traffic in the nation. The biggest choke points are the 2-lane section of I-5 at the Rose Quarter, the 3-lane Vista Ridge Tunnel on US 26, and the Interstate Bridge. People lost 72 hours in 2022 stuck in congested traffic.

Transportation officials in the late 1950s and 1960s planned for Portland to have a “ring road”, with bypass alternatives to I-5 on both the east and west side of downtown. I-205 was completed first, opening in Dec. 1982. Sadly, Portland killed the construction of the western bypass that was supposed to be completed by 1990. Regional population has doubled since I-205 opened; yet no new vehicle capacity has been added.

Numerous government studies highlighted the need for multiple crossings of the Columbia River. These included bridge options just north of the PDX airport into central Vancouver. Most recently, the Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council (RTC) released their “Visioning Study” in 2008, leading up to the failed CRC. It identified the need for two new bridges, one west of I-5 and the other east of I-205.

Instead, citizens now deal with an extremely expensive replacement of the two I-5 bridges over the Columbia, both of which are deemed “safe” by both the Oregon and Washington Departments of Transportation. The original structure built in 1917 received a major safety upgrade in 1958. The other bridge was built in 1957 and is newer than most of the Portland area bridges over the Willamette River.

With the US Coast Guard opposed to the current LPA with only 116 feet of marine clearance, citizens might hope officials on both sides of the river will demand a fresh look at what is being proposed. The people’s top priority is reducing traffic congestion and saving time. That means adding vehicle capacity, either on I-5 or on a bypass, just like Baltimore has.

The Ports of Portland, Vancouver and Camas-Washougal can weigh in with a fresh look at what a larger turn basin on the river might offer, along with a bridge meeting the desired 178 feet of clearance. Perhaps they might even push for the “unlimited” clearance an Immersed Tube Tunnel offers, with no safety risks to marine traffic.

Also read:

- Delays expected on Northwest 99th Street during water quality project constructionClark County will begin construction in July to install a stormwater filter vault on NW 99th Street. Drivers can expect delays, but lanes will remain open during the work.

- POLL: What’s the biggest concern you have with the current I-5 Bridge replacement plan?As costs rise and Oregon’s funding fails, concerns mount over the current I-5 Bridge replacement plan. Clark County Today asks readers: what’s your biggest concern?

- Plan ahead for ramp closures on I-5 near Ridgefield, July 8-9Travelers on northbound I-5 near Ridgefield should prepare for ramp closures July 8–9 as WSDOT crews conduct final testing of new wrong-way driving detection systems. The closures affect exits 9 and 11, including the Gee Creek Rest Area.

- Oregon DOT director calls transportation funding bill failure ‘shocking,’ warns of layoffsODOT Director Kris Strickler warned staff that up to 700 layoffs are imminent after lawmakers failed to pass a transportation funding bill, deepening the agency’s $300 million shortfall.

- New crossing opens over SR 500 in VancouverWSDOT has opened a new pedestrian and bike bridge over SR 500 in Vancouver, restoring direct and ADA-accessible access for people walking, biking, or rolling.