Washington has $224-$356 million identified; Oregon only $15 million

For the past year, members of the Oregon and Washington legislature have been meeting, trying to address issues and resolve differences in order to restart a replacement of the Interstate Bridge. These discussions were allegedly motivated by a requirement for the two states to repay $140 million federal transportation dollars expended on the Columbia River Crossing (CRC).

Washington’s share of that money is about $46 million and Oregon’s share is about $93 million. Yet last week, retired economist Joe Cortright reiterated his claim that selecting the “no build” option would allow both states to avoid repayment. Furthermore, Washington has allocated $35 million to the current effort, which is 75 percent of their repayment obligation. Citizens might wonder why not either claim the “no build” option or simply pay the federal government back. The states could then start with a clean slate with no previous time deadlines or location constraints.

On Tuesday, the Bi-state Bridge Committee of legislators will meet again. They will be given an advance briefing by the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project (IBRP) team on the Conceptual Finance Plan (CFP) that must be submitted by Dec. 1.

Recall that the previous $3.5 billion CRC replacement project included light rail and millions not related to the 5-mile bridge influence area defined by the “Purpose and Need” statement. That unrelated spending included a new TriMet office building, an upgrade to Portland’s Steel Bridge, a $51 million expansion of TriMet’s Gresham maintenance facility, and a “curation facility” in Vancouver..

The IBRP website posted the briefing slides in advance. Here are some of the numbers legislators will be presented.

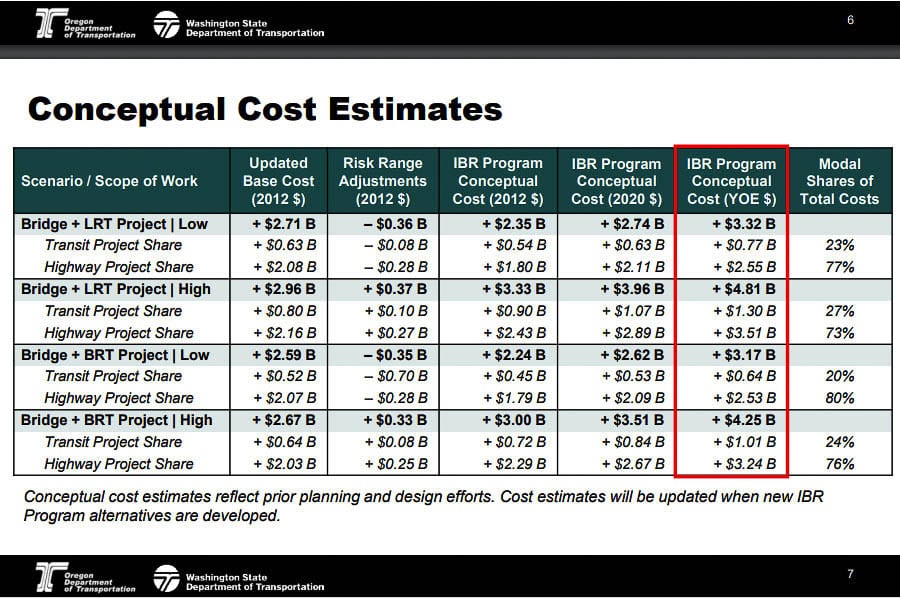

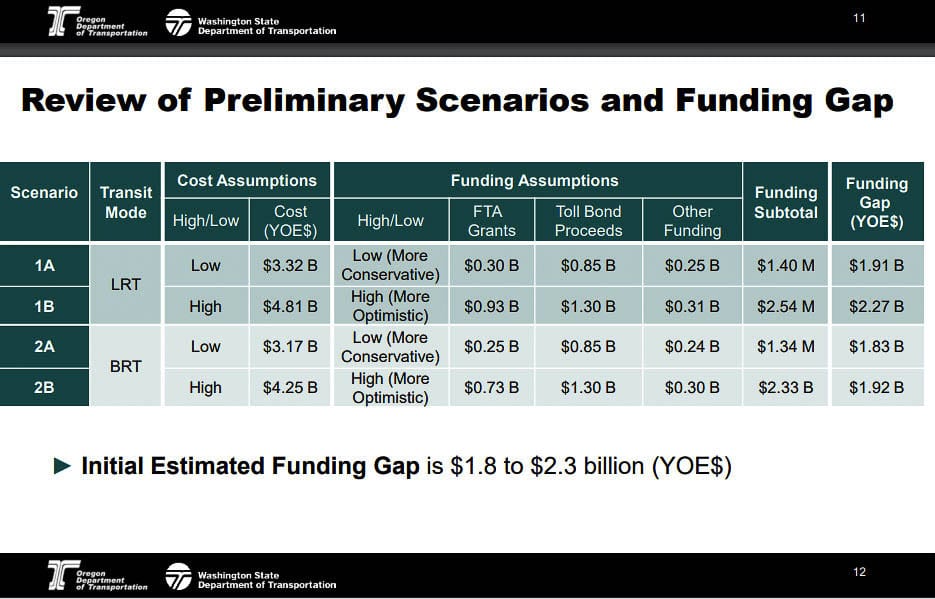

The IBRP team provided “low” and “high” cost estimates for multiple scenarios. Scenarios 1A and 1B have light rail; scenarios 2A and 2B have bus rapid transit (BRT). All scenarios include “toll bond proceeds,” federal funding via “FTA grants,” and “other funding” calculations. The low estimates are labeled “more conservative” and the high estimates are “more optimistic.”

The 1A low cost estimate is $3.32 billion. The 1B high cost estimate is $4.81 billion. Both include light rail. The 2A low cost estimate is $3.17 billion and the high 2B cost estimate is $4.25 billion for the BRT options.

Citizens might recall that in the CRC, the light rail cost was $830 million. They might wonder how excluding light rail produces only a $150 million smaller cost in the “low” BRT estimates, or a $560 million smaller cost in the high BRT cost estimate. At first glace, it would seem bus rapid transit isn’t that expensive. For example, The Vine cost $53 million for a 6-mile BRT line operated by C-TRAN.

Under the funding assumptions, the low estimate for federal light rail funding delivers $300 million versus $930 million for the high estimate. The $300 million conservate estimate is 65 percent lower than what the CRC hoped to obtain for their light rail funding.

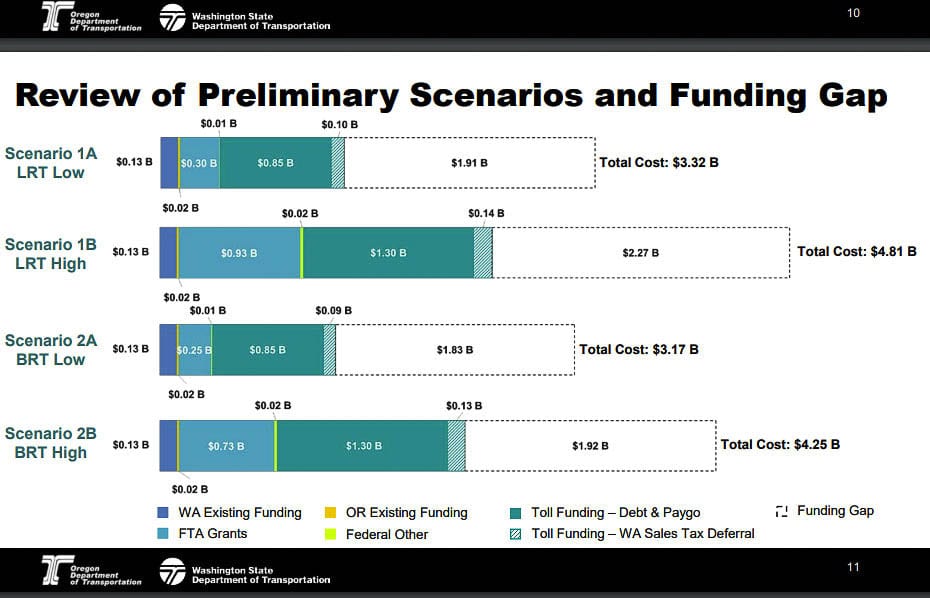

More eye-opening for taxpayers is the “funding gap” in the IBRP plan. They show a $1.83 billion shortfall for the low BRT project estimate and $2.27 billion shortfall for the high light rail estimate. As Cortright said in a previous interview, “I have no idea where it is they think they’re going to get the money for this.’’

The tolling revenue assumptions raise questions. In the CRC, the high estimate was $8 tolls. Oregon is moving forward with plans to toll both I-5 and I-205 beginning “at the border” with Washington. If Oregon plans to add their tolls on top of the bridge tolls, how high would the tolls have to be to produce revenue for both a replacement bridge and for Oregon’s other transportation needs?

Finally, the report shows funds needed between now and 2025, when construction might begin. The low estimate is $185 million and the high estimate is $383 million. Keep in mind, this is, at least in part, to avoid repaying $140 million federal dollars already expended nearly a decade ago.

Under “funding options,” the IBRP team indicates they have $35 million from Washington and $15 million from Oregon currently committed. They also show $97 million from Washington that was set aside in the 2015 gas tax bill for the Mill Plain/I-5 interchange.

The passage of the 2015 Washington gas tax was the largest gas tax increase in state history. Then County Commissioner David Madore asked Vancouver elected officials and Regional Transportation Council Board members what the $97 million was for, but he was unsuccessful in getting an explanation. Ultimately, then Vancouver City Councilor Jack Burkman admitted the revamp of the Mill Plain/I-5 interchange was exactly the design for the interchange contained in the CRC plans.

Publicly, everyone was claiming the CRC was “dead,” yet $97 million had apparently been set aside for a future resurrection of the CRC.

The finance plan indicates there is a “high probability” of raising $850 million to $1.3 billion via bonds tied to tolling revenues. But with Oregon already moving ahead with their own tolling, how much additional money will Wall Street loan, knowing tolls on top of existing tolls could potentially cause a large number of drivers to divert to a lower cost I-205 routing across the river?

The IBRP plan offers three other projects in Washington state as examples. The 520 “floating” bridge across Lake Washington, the Alaska Way viaduct, and the Puget Sound Gateway project.

The largest amount of federal funding allocated was 25 percent of the 520 bridge project, with 23 percent to the Alaskan Way project, and just 4 percent to the Puget Sound Gateway project. Citizens might ask what are the odds a replacement bridge will get 25 percent of a potential $4.8 billion project that has already burned through $140 million federal dollars nearly a decade ago?

In the various cost estimates, the “highway project” costs range from $2.09 billion to $2.89 billion. No where do they break out the cost of simply replacing the bridge.

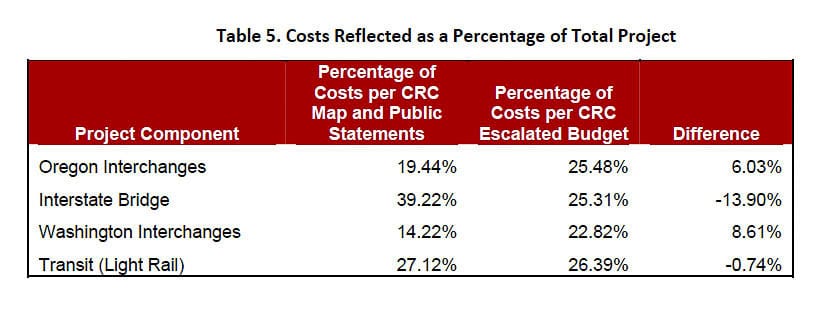

In the failed CRC, forensic accountant Tiffany Couch scrutinized all the financial records of the project. In her report number 6, she stated the following.

“According to the CRC’s own detailed budgets, the costs to build the interchanges in Oregon and Washington are expected to cost hundreds of millions more than what is being reported to legislators, public officials, and the citizens of Oregon and Washington. Conversely, the CRC’s own detailed budget shows that the cost to tear down and rebuild the interstate bridge is hundreds of millions less than what is being reported.’’

Couch revealed the actual cost of the bridge was $791.3 million instead of the $1.2 billion they told citizens in numerous publications.

If the IBRP team is truly looking to simply replace the bridge rather than resurrect the entire CRC, why don’t they list a cost for just replacing the bridge?

The funding shortfall is shown graphically for all four options. The shortfall ranges from $1.8 billion to $2.3 billion. But showing the percentage of each project that is “unfunded” is revealing. Options 1A and 2A have 42 percent possible funding. Options 1B and 2B have almost 53 percent and 55 percent possible funding.

Citizens might also wonder when both states are being locked down for the second time, and even more people working from home, how much will gas tax revenues decline for the two states? With more people working from home, others will wonder how long will it take for traffic to return to pre-COVID levels?

An April headline reads: “Oregon’s highway trust fund faced ‘unsustainable’ financial crisis even before COVID-19 hit”. Oregon just passed a $5.3 billion transportation package in 2017. How likely is it they will raise taxes again to contribute their share? Metro area taxpayers just rejected a $5 billion transportation funding proposal that was mostly a SW Corridor light rail project.

The IBRP plan does not break down the costs nor the revenue contributions by state. They show a total of $15 million in Oregon funding, and a range of $224 million to $356 million from Washington state. That means Oregon is $209 million to $341 million behind an “equal” contribution.

One of the issues in the CRC was a strong sense that Southwest Washington citizens would be footing the lion’s share of the tolls paid for the bridge. According to the CRC’s FEIS, Washington citizens comprise more than 65 percent of all commute time trips in the morning and afternoons, Couch reported.

With a projected funding shortfall of $1.8 billion to $2.3 billion, citizens might wonder why they don’t offer a “bridge only” option? Is the IBRP team waiting for direction from legislators or ODOT and WSDOT officials? Could it be this too is “a light rail project in search of a bridge” as an Oregon Supreme Court Justice ruled regarding the original CRC?

Two years ago was the first meeting of the committee of Oregon and Washington legislators. “Sen. (Annette) Cleveland was quick to say that this week’s meeting was about defining the process of getting to a project, rather than talking about any specific ideas.” Others said there was no specific project. Sen. Ann Rivers said this wasn’t the CRC.

As ClarkCountyToday.com reported: “Sen. Rivers wrapped up with a few comments for the gathered crowd, many of whom she said had sounded alarm bells that “the CRC is back! The CRC is back!”

“I hope that you will sound the alarm that you were wrong,” said Rivers. “I hope you will go to your blogs and say, ‘wow, they don’t even have a process yet. Maybe I should reserve judgement and see what they come up with.’”

Citizens can watch the Bi-State Bridge Committee meeting here. The meeting is Tue., Nov. 24 from 1-4 p.m. To offer public comments, citizens must sign in 24 hours in advance of the start of the meeting (here).