Washington and Oregon are each awash in money for transportation programs

President Joe Biden signed the unprecedented $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) this week. Included is “at least” $14 billion in federal funding for Oregon and Washington, according to the politicians touting all the money they are delivering to each state. While the money is spread among many types of “infrastructure,” transit, roads and bridges are among the key focal points.

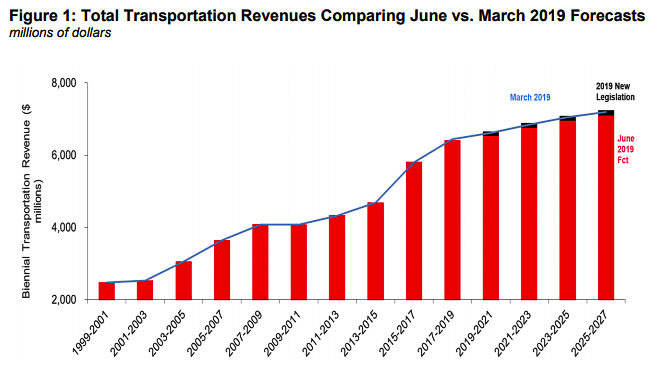

According to Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden, Oregon alone will receive $5.36 billion. Washington is expected to get $8.6 billion. Wyden touts the possibility of “more” being available via competitive “grants.” This money is added to the $6.6 billion (biennium) Washington will spend on transportation and Oregon will spend $3.3 billion in highway fund revenue for 2022-23.

“The total will be higher than that, once the new programs are established and funding from competitive grants is factored in,” Wyden said. “The competitive awards for projects in Oregon will vary from year to year, so there is no way to know yet exactly how much Oregon will receive over the five-year span.”

Under the IIJA package, over the next five years Washington will receive around $4.7 billion for highways and $605 million for bridges and another $1.8 billion in public transportation spending, according to Washington Sen. Patty Murray. There is a special $5 billion Megaprojects Grant Program included in the bill that could fund the Interstate Bridge project, according to one report.

Commuters in the Portland metro area and Southwest Washington are looking at the signing of the federal infrastructure bill, and wondering about Oregon’s plan to toll all major highways in the region. This of course will have a huge impact on the over 70,000 Clark County residents (pre-pandemic) commuting across the two Columbia River bridges to work in Oregon.

ODOT officials indicate they will move forward with their plans for tolling regional freeways and highways,despite the federal funds. Why?

“We’re getting that question a lot and the reality is that this infusion of resources into the transportation system, while significant, is not enough to be able to pay for those projects in the absence of tolling,” Travis Brouwer said. He is the assistant director for Revenue, Finance and Compliance at ODOT.

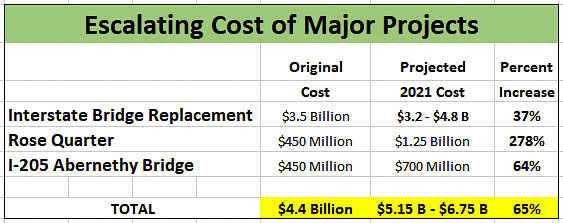

Brouwer said the current I-205 project is estimated to cost about $700 million. The I-205 Abernethy Bridge seismic upgrade and adding a 6-mile lane to Stafford Rd. was expected to cost $450 million initially and increased to $500 million in 2018. Today, ODOT mentions $700 million being needed to complete the project.

ODOT is in the environmental analysis phase to add tolls on I-205 and across the region on I-5 as well. Brouwer said the tolls will assist in other areas of funding gaps, such as the Rose Quarter and Interstate Bridge.

The I-5 Rose Quarter project was originally sold to the Oregon legislature as costing $450 million. The price tag remains a question today, as officials are trying to flesh out final details on an expensive “highway cover” that will create real estate, to be developed by the minority community in Albina. But recent cost estimates are in the $1.2 billion to $1.5 billion range.

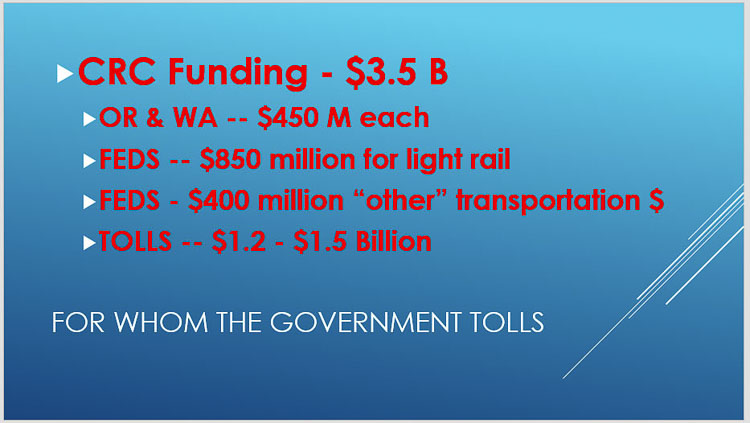

The Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBR) does not have a specific bridge design. Administrator Greg Johnson has told citizens they hope to narrow down three major options by early next spring, with a final choice moving forward by March. They told the 16-member Bi-state Bridge Committee of legislators that “if” they were to build the previously failed Columbia River Crossing (CRC) today, the price could run from $3.2 billion to $4.8 billion.

In spite of the seemingly never ending escalation of costs, (ODOT failed to include inflation estimates in earlier cost estimates for their HB 2017 package) the total cost of these three major transportation and infrastructure projects is in the $5.4 billion to $7 billion range. On the surface, that could consume half the federal money, leaving half for other projects and infrastructure.

Clark County Today previously presented several examples of bridges that have been built for under $1 billion. The actual bridge part of the CRC was $792 million. If the Glenn Jackson (I-205) Bridge was built today, the $169.6 million spent in 1982 would be $486 million in 2021.

In 2017, the Oregon legislature passed the HB2017 transportation package providing $5.3 billion in transportation funding. It was called “the most ambitious highway upgrades in a generation.” Oregon is getting “at least” that much from the IIJA package.

HB 2017 had a 4-cent gas tax hike initially and another 6 cents over eight years. There was also a $16 vehicle registration fee increase and 0.1 percent payroll tax and 0.5 percent tax on new car sales. It was “the most comprehensive transportation bill that the Oregon legislature has ever passed,” said Sen. Lee Beyer (Democrat, Springfield.

In 2015, the Washington legislature approved a $16.1 billion transportation package. It raised gas taxes by 11.9 cents along with car tab fees and freight hauler weight fees. The current IIJA package is more than a 50 percent increase in unexpected funding.

A September transportation revenue forecast from the Washington Office of Financial Management estimated federal highway revenues would be around $800 million per year through Fiscal Year 2025. The sudden infusion of IIJA money is 10 times that amount, spread over five years.

The Oregon Department of Transportation will collect just over $5.1 billion in total revenue during the 2021-2023 biennium; 23 percent from the federal government or $1.1 billion. The IIJA package will double that per year for the next five years.

Oregon’s gas tax increases 2 cents in 2022. Portland collects an additional 10 cents per gallon gas tax for transportation.

So what is the need for tolling revenues?

In August 2018, Oregon’s Peter DeFazio was against tolling existing roads that are already paid for.

DeFazio said he is in favor of efforts to add more capacity to Interstate 5 north of Eugene. It was reported he is opposed to efforts to make I-205 a toll road. He is not supportive of toll roads generally, and he is adamantly opposed to placing tolls on roads or bridges which have already been paid for by taxpayers.

In his words, a toll would be imposed on freeways in Oregon “over my dead body.”

IBR’s Johnson shared the following with Clark County Today, prior to the final passage of the IIJA package.

“Tolling is a part of that solution, because neither one of the states can afford to take this bigger chunk out of their program and still get the other things they need to get done,” he said. “This would cripple their programs for years to come, if they had to pay for it solely out of revenue that comes to them from either state or federal sources. Tolling is a best practice.

“Nobody wants to pay for something that they haven’t been paying for in the past,” Johnson said. “This is human nature. But once again, to get a new bridge and to get hopefully some of the things that we think are going to be benefits here, we think that tolling has got to be a part of that picture.”

Following IJAA passage, Clark County Today asked Johnson if he still believed tolling will be part of his team’s proposal.

We are encouraged by the criteria in the new federal grant programs and confident that the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) program is well positioned to compete. The investment each state will receive from the infrastructure bill over the next five years was allocated to fund specific activities and categories of projects. Much of the funding also comes with requirements to spread it across geographical areas or to local jurisdictions and the backlog of work in both states for maintenance of the existing system is tremendously behind. This means the federal funding allocated to Washington and Oregon will be allocated to several smaller infrastructure projects across the region, not megaprojects like the IBR program.

The IBR program is focused on providing a safe, efficient, and earthquake-resilient replacement bridge and multimodal corridor that is accessible to all travelers, whether traveling by vehicle, transit, or active transportation. The multimodal aspect of the IBR program is key critical to accessing federal funds, and one key to securing federal funding is in demonstrating that there is a funding commitment from each state. We know that tolling is going to be a part of this equation. When considering bridges and projects across the country that are similar in scope to the IBR program, neither the state nor the federal government fully funds the program. The amount of funding we receive from both states and from the federal government will impact how much the users of this bridge will pay in tolls.

The “cost of collection” for tolling is extremely high – over 40 percent on Seattle’s I-405. Why would elected officials and transportation bureaucrats burden taxpayers and lose 40 percent or more up front? The gas tax offers a 1 percent cost of collection and is much more efficient.

There was an 81 percent drop in I-405 tolling revenues due to the pandemic lockdown. Financially, the “tolling system” had to be bailed out by the Washington State Legislature with other money.

Transit spending

In the Oregon IIJA package is $747 million allocated to public transit. TriMet is the one major transit agency in the state, so it will likely get the lion’s share of those funds.

Will TriMet and the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) choose to allocate the lion’s share of that money to “restart” the Tigard-Tualatin light rail line? Local funding for that project was rejected by Portland area voters a year ago when the $5 billion Metro transportation bond failed a year ago. According to the City Observatory, “all of the Multnomah County precincts through which the project would have run voted against the measure.”

One of the alleged reasons for that bond failure was “the Christmas tree approach,” promising something for everyone. That may sound eerily like the current Interstate Bridge Replacement Program.

Another option is for Oregon to try to use the money to extend light rail as part of the Interstate Bridge replacement. In the failed CRC, the light rail extension was $825 million according to forensic accountant Tiffany Couch.

Combining Oregon’s $747 million in transit funding with Washington’s allocation of $1.8 billion in public transportation spending delivers over $2.5 billion for transit. That would make it appear that tolling would not be needed to fund any transit component on the IBR Program.

What do citizens want?

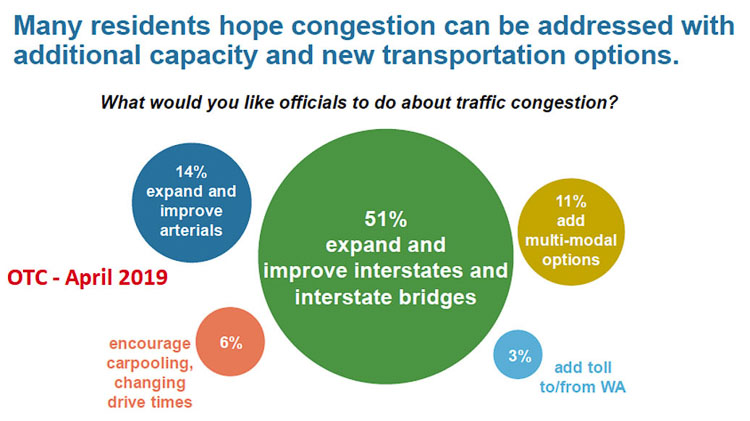

Traffic congestion relief is the people’s primary frustration and top priority for the IBR project and metro area transportation spending. The I-5 corridor is congested half of each day. The IBR Program has already admitted that the project will deliver minimal savings in travel time for those driving cars and trucks.

An April 2018 OTC survey found 51 percent of citizens want to “expand and improve interstates and interstate bridges;” another 14 percent want expanded arterials. Only 3 percent wanted tolls to/from Washington.

A January 2019 Metro poll showed the number one priority was roads and highways. It indicated 31 percent of citizens want “widening roads and highways” as their top priority.

The Portland Tribune summarized: “On its own, improving public transit is a lower priority than making road improvements and the more overarching goal of easing traffic — voters still overwhelmingly rely on driving alone to get around,” read the poll’s conclusions.

During a meeting with legislators, Johnson responded to a question by Oregon Sen. Lew Frederick. “How much time will drivers save rather than just saying congestion will be addressed?” He referenced citizens’ dissatisfaction with the one minute improvement in the failed Columbia River Crossing (CRC) effort.

A year ago, Frederick reminded the IBR Program team people value their time the most and the one minute time savings in the CRC. “That is not enough,” he said. “That does not speak to what people want.”

The Clark County Council recently added their desires on behalf of the citizens on the north side of the river. They asked that the overwhelming priority be on reducing traffic congestion. They also said “no tolls.”

Councilor Karen Bowerman led the effort, introducing a two-and-one-half page set of issues and concerns at the August Council Time discussion. “There is one primary goal associated with the bridge replacement project that rises above various secondary goals, and that is to significantly reduce traffic congestion.”

The language the council adopted opposing tolls as a means to pay for the project triggered the fiercest discussion. Councilor Temple Lentz accused the others of “ignoring reality.” Yet the others point out how that policy creates “roads for the rich” (in reference to Vancouver Councilor Bart Hansen’s description) because congestion pricing could make regular crossing of the bridge prohibitively costly. Clark County voters have repeatedly voiced their opposition to tolling, especially in the failed CRC.

There are now “at least” $14 billion reasons the Interstate Bridge Replacement will keep moving forward. How much of that money the project gets, remains to be seen. How much Oregon and Washington will contribute in additional money remains to be seen.

A year ago, both states were told by the IBR Program team to expect to pay $1 billion or more. There was a $2 billion funding shortfall, legislators were told. The federal government has now covered that shortfall.

Will the program avoid becoming “roads for the rich?” Or will Bart Hansen’s concern become reality? The $14 billion in unexpected federal funding could seemingly make them “roads for all.”

Congressman DeFazio helped deliver significant money to both states. Will he continue to defend the average citizen with his “over my dead body” pledge? Or will citizens be paying to drive on roads and highways they’ve already paid for?