The goal is a seamless treatment program that starts before patients leave the hospital

VANCOUVER — In 2017, 48,000 Americans died due to an overdose on opioids. That included well over 700 people right here in Washington state, and 39 in Clark County. By way of comparison, 28 people in Clark County died in traffic crashes that same year according to the Washington State Department of Transportation.

The epidemic of Americans addicted to these pain-numbing, mind-altering drugs has become headline news in recent years. Major pharmaceutical companies are facing multi-million dollar lawsuits for allegedly conducting a massive misinformation campaign about the addictiveness of drugs like Vicodine and Oxycodone, while paying doctors to prescribe them.

In the process, millions of Americans have become dependent on these pain-relieving medications for everything from post-surgery recovery to a bad toothache. And as medical professionals have adopted more stringent standards for prescribing opioids, many people have turned to much more dangerous street drugs such as heroin and fentanyl. Street drugs are notoriously dangerous, often leading to overdoses and even death.

While lawmakers and medical experts continue to work on prescription guidelines to limit the use of opioids, others are focused on helping to end the stigma of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) and getting people help when they’re at their most ready for it.

Enter Annie Neil, a registered nurse at PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center. She, along with Doctor John Hart, helped secure a $426,000 grant from the Washington State Health Care Authority to create a program to get OUD patients treatment before they leave the hospital.

Previously, Neil says, many patients would come in for overdoses and leave with an appointment to see an addiction counselor. But for many people the next craving would come before that appointment, and very often they simply wouldn’t show up.

“So now we have this window of opportunity to treat them right away and prevent any sort of gap. And that’s the goal,” says Neil.

Changing the model

Neil says when they found out about the state grant program it was just about four days before the deadline. She, Dr. Hart, and Eric McNair Scott of the Southwest Washington Community of Health (SWACH) worked late hours through the weekend to put together their proposal.

“We came up with the proposal and submitted it literally five minutes before the deadline,” says Neil. “And we found out a week and a half later that we had gotten the grant so then we had to build the program lickety split.”

Part of that has included extensive work in getting doctors throughout the hospital trained so they can write prescriptions for opioid treatment medications, such as Suboxone and Buprenorphine, which work to ease cravings without causing the same “high” associated with opioid-based drugs.

“The dilemma in this whole thing is that physicians can write a prescription for opioids that patients can become addicted to, but they have to take a special eight hour training in order to write a prescription for the drug that’s going to treat their brain disease, which is the opioid addiction,” says Neil.

Under this new program, hospital doctors and nurses not only look for patients who have come in specifically to be treated for an overdose, but those exhibiting symptoms of opioid dependency.

“They will leave the hospital,” says Neil. “I’d say that’s a big percentage of people that leave what we call ‘against medical advice.’ And now we’re really learning to recognize what that’s about, that when somebody wants to leave against medical advice, often there is an addiction problem there and they become candidates for this program.”

That’s usually when someone like Nurse Neil or Doctor Hart get a page, requesting that they come sit down with the patient and get a sense of what’s going on. If they are dealing with opioid dependency they’re offered a chance to begin treatment in the hospital, and receive a prescription before they go home.

“When somebody is in withdrawal, they are desperate to get opiates,” says Neil. “And it’s actually the best time to get them Buprenorphine. Because the more withdrawal they’re in, the better this drug works, and they feel so much better when they get the medication. And it doesn’t make them high is the thing, it doesn’t have the impact on the brain in the same way that opiates do.”

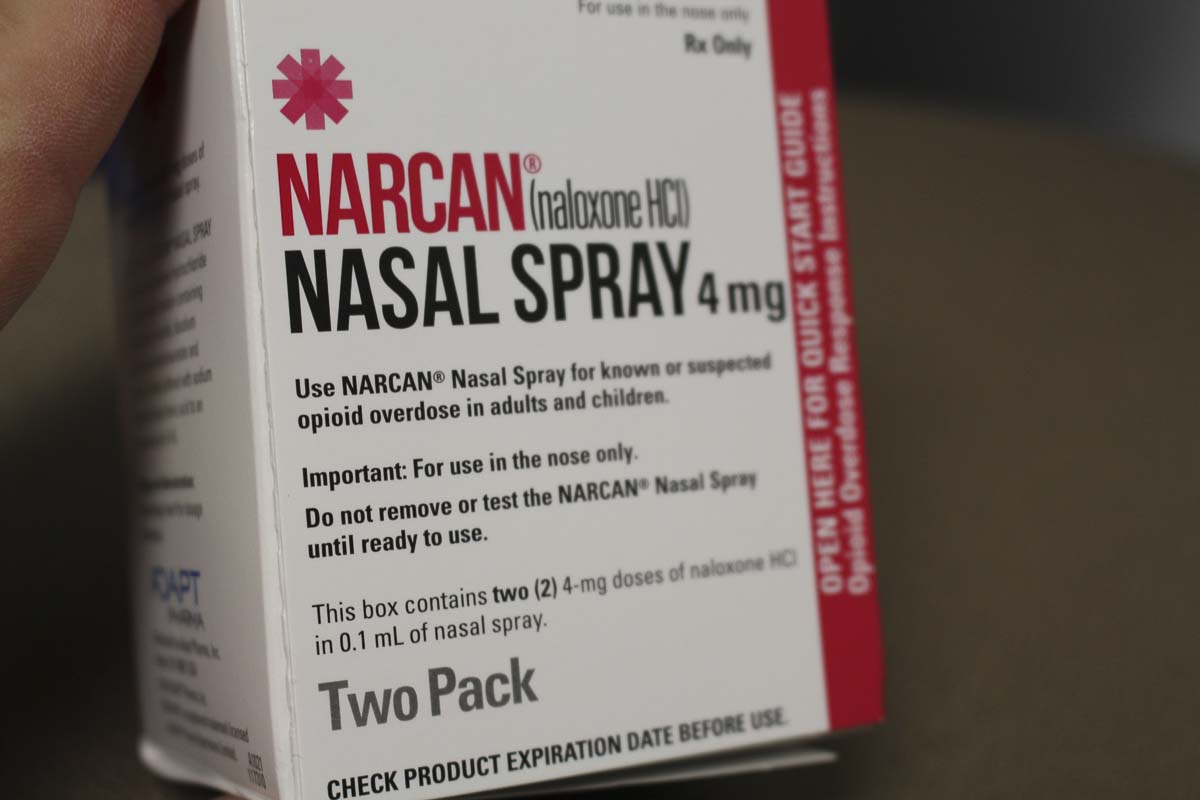

Even if patients decline to enter the treatment program, Neil says they’re sent home with Narcan, an overdose treatment medication, and instructions on how to use it.

Setting the standard

Neil says, to her knowledge, the PeaceHealth Southwest program for opioid dependency is a first on the west coast. And increasingly, it is the model that hospitals are looking at in order to hopefully interrupt substance use disorders before the cycle can continue.

That is being done with the help of partners like Lifeline Connections, which is usually the next stop for anyone who agrees to enter treatment at PeaceHealth Southwest. Their programs include detox, mental health, and continued medication-assisted treatment.

And that’s the goal of programs like SWACH, which are working to build a connected network of drug treatment, so people who are struggling with addiction find a seamless experience when it comes to getting help. Instead of going to the hospital, getting treated, and then being left on your own to seek an addiction program, the goal is to get them help right away and then onto the next stage without any gaps.

“We’re not going to try to solve all their problems, we simply want to get them on the treatment and connect them with continued treatment at discharge,” says Neil. “Because if they leave the hospital, without treatment, their chances of going out and getting an opiate again, or heroin or whatever they’re going to use, and their chance of dying, is pretty high.”

The grant will fund the PeaceHealth Southwest program for two years, while tracking how many patients are treated and what their rate of success is. The goal will be to have specialists embedded at the hospital and at Lifeline, and to introduce new resources throughout the second year that the state is providing. That will include follow-up with patients over the phone to ensure that they are continuing with treatment and finding success in getting free from their addiction. If the program proves successful, it may become a model for other hospitals around the region.