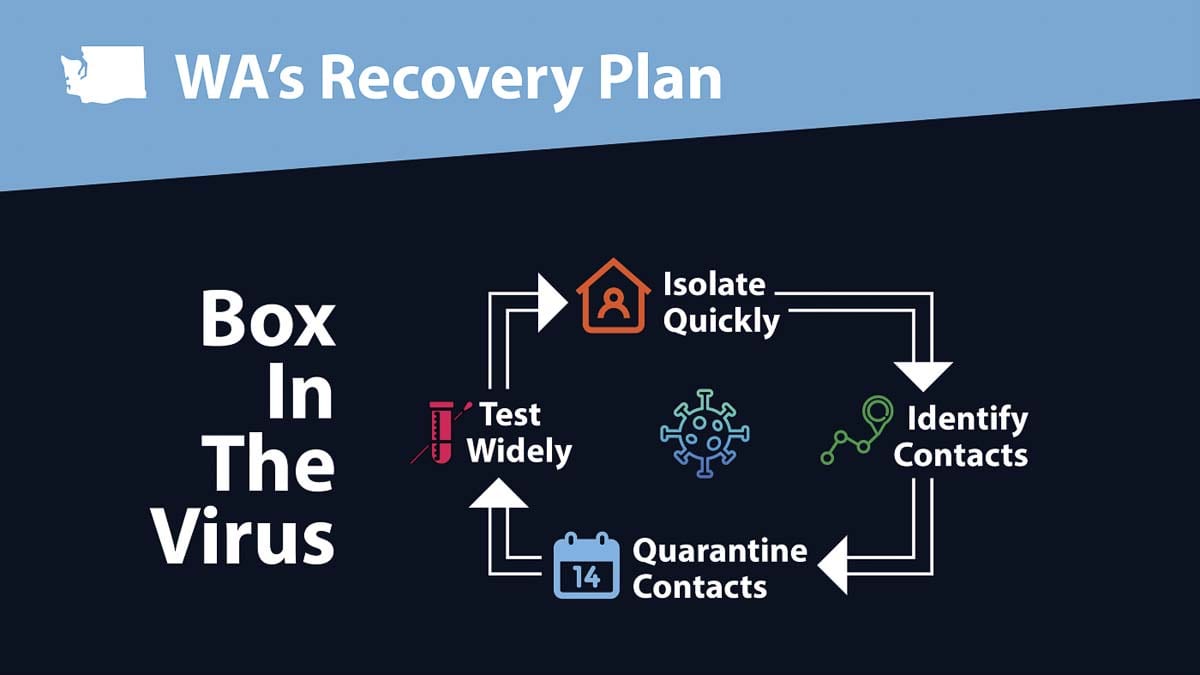

Contact notification plays a key role in pandemic response

CLARK COUNTY — During the week of May 18, as word trickled into Clark County Public Health about cases of COVID-19 popping up at a Vancouver frozen fruit packing facility, the county’s contact notification system was put to its first major test.

Just a few days after the first confirmed case at the facility, members of the Clark County Council approved spending $9.1 million to contract with The Public Health Institute, a nonprofit specializing in a broad range of healthcare-related projects.

“We’re the Swiss Army knife of institutes,” jokes Marta Induni, who is leading PHI’s Tracing Health program.

The Tracing Health program was born partly out of a partnership with Oregon Public Health Institute and Washington County, which was the first to consider using a larger entity to quickly ramp up staffing based on need.

During the measles outbreak in 2018, Clark County Public Health could rely on help from the state and other counties when it came to case investigations and contact tracing. With COVID-19 occurring statewide, and even across the country, there was little outside help available.

Under normal circumstances, the county would have approved a budget to allow public health to begin hiring dozens of temporary workers. Doing so would have required significant time and resources.

Within six days of PHI signing the contract with Washington County to do contact tracing, they had received over 1,000 applications.

“Because we were already doing that work in Washington County, we were able to quickly adopt similar models for Clark County,” says Induni. “We had hundreds of applications within just days. It was amazing.”

PHI says 90 percent of the people that were hired spoke at least two languages, covering six total languages in addition to English.

Those skills helped during the Firestone Pacific Foods outbreak, with many of the employees speaking English on a limited basis.

“Because the position is epidemiology based, we expected more in terms of education,” Induni adds. “But we also wanted to attract a very diverse workforce, and so we also accept people with certifications in community health work, those sorts of things, so you have an incredible bilingual force.”

Induni says a huge percentage of the people who applied to fill the positions said it wasn’t about the money as much as it was about the ability to do something good for their communities during the pandemic.

“The funding only goes to the end of October,” she says. “So it’s not even a huge career move right now for people. They really are on the phones because they want to help.”

These “micro teams,” as Induni calls them, are made up of eight contact notifiers, one supervisor, and a resource coordinator whose job is to interface with local officials on any requests for things like food assistance, prescriptions, or other services for people being asked to isolate.

“We’ve had a … couple people who actually needed medical care,” says Induni. “And so we work with the county to get them that care.”

“Our experience with PHI has exceeded our expectations,” said Dr. Alan Melnick, Public Health director and Clark County Health officer. “PHI immediately provided assistance, and as a result, we were able to control the (Firestone) outbreak and keep it from spreading further into our community.”

Clark County Public Health does initial case investigations in house, with registered nurses asking confirmed patients a series of questions to determine where they may have been since becoming contagious. Those questions are voluntary, and people can choose not to answer any or all of them.

Any close contacts, defined by the Centers for Disease Control as being within six feet of someone for at least 15 minutes, may be contacted by notifiers, though information about the person who may have exposed them is not disclosed by the county.

“It’s not just a courtesy thing,” says Induni. “It’s protected health information.”

That doesn’t mean the person at the other end of the line can’t sometimes figure it out.

“Because, you know, ‘I went to see Uncle Bob last weekend and he was sick,’” Induni says.

The notifiers will give the close contact information about self-quarantining, and advise them to isolate at least 14 days from their last contact with the known case.

“We also do what’s called active monitoring,” says Induni, “which is, we actually check in with these people every day, to see if they’re sick, to see how they’re doing.”

Clark County Public Health has been clear that the quarantine is entirely voluntary, and that notifiers will not be allowed to ask if a contact has been following the request. Monitoring can be done via phone call, text messaging, or email, depending on the person’s preference.

The contract allows Clark County to scale its response as necessary. The state’s guidelines for moving from one phase of reopening to the next calls for counties to be able to reach close contacts within 48 hours of a case being confirmed.

Induni says the average person has five close contacts, all of whom need to be contacted on a daily basis until they’ve finished their quarantine. Obviously not everyone will choose to be monitored, but the numbers can add up quickly.

“Right now we have three teams in place in Clark County,” Induni says. “We have the ability to expand if needed, but right now, those three teams with about 24 contact tracers seem to be holding down the fort.”

Clark County has the ability to ramp up to 74 contact tracers if necessary, and Induni says they can hire and train them quickly if called upon.

“There’s a Johns Hopkins training, I think that’s about five hours,” Induni says of their training procedure for new hires. “And then we do some role plays and some scenarios where people kind of think through good information is to have in your back pocket, especially when you’re trying to talk to resistant people.”

Each contact notifier has a script in multiple languages, as well as access to real-time translation to assist with language barriers.

“We’ve got a really good workforce. We have alacrity, we can move around quickly, and we’ll grow when we need to,” Induni sums up.

Clark County outbreak update

Since last Friday, Clark County has confirmed 24 additional cases of COVID-19, bringing the total to 656, with 28 fatalities. The last death was reported on June 5.

The number of confirmed cases in Clark County hospitals has risen sharply, from just two last Friday, to 11 as of Tuesday. The county still has nearly half of available hospital beds open, however.

Barring any changes, Clark County would be allowed to apply for Phase 3 as of June 26, which is three weeks since the move to Phase 2.

The state’s reopening guidelines allow for up to 25 new cases per 100,000 residents in the past two weeks, which would put Clark County’s cap at around 120 in the past 14 days. Currently, the county is trending at 16 new cases per 100,000 residents over the past 14 days, even with the outbreak at Pacific Crest Building Supply in Ridgefield.

A total of 24 employees there have tested positive, 14 of whom live in Clark County. A total of 101 tests came back negative, and 29 people are still pending.

There have been no additional cases linked to Firestone Pacific Foods, which hit 132 confirmed cases out of 328 employees and close contacts who were tested.