C-TRAN Board in turmoil over potential light rail funding

Rep. John Ley

for Clark County Today

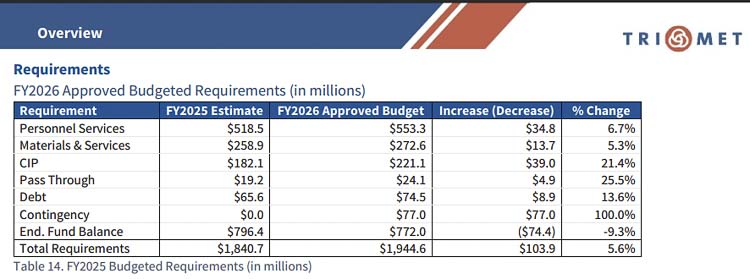

Portland’s TriMet had an operating loss of $850 million last year. Operating costs are up 53 percent since 2019. Last fall they agreed to employee pay raises of 13.6 percent over the next four years. The FY26 budget (beginning July 1) calls for 5.6 percent more in spending including $221 million in capital improvements, of which $66 million is to buy replacement light rail vehicles.

They are presently demanding the Oregon legislature give them a 400 percent increase in a statewide transportation “head tax” on employers, known as STIF. “TriMet is budgeted to utilize $83.7 million in STIF funding in FY2026” they report in their budget. Legislators are debating a possible 80 percent increase in the tax, far short of TriMet’s demands.

At the same time, the Portland transit agency continues to push expansions and huge capital expenditures. They demand MAX light rail be part of the I-5 Interstate Bridge replacement proposal, including Clark County paying $7.2 million per year towards operations and maintenance of the transit component. There is also a demand for 19 new light rail vehicles at triple the actual cost, for the 1.8 mile extension of the Yellow Line into Vancouver.

The C-TRAN Board of Directors is presently in turmoil over TriMet funding issues. Cross river ridership remains flat on C-TRAN express routes. “It is clear there is no need for light rail, and bus service can easily continue to meet the demand for public transit at a much lower cost, both now and in the future,” said Camas resident Doug Tweet.

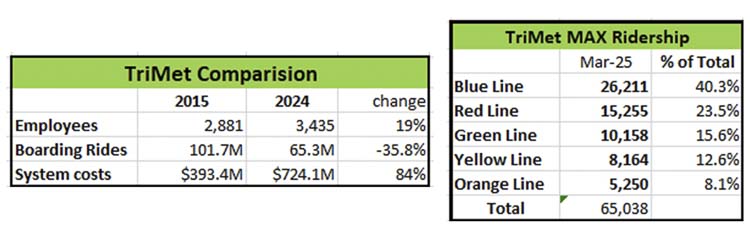

TriMet historical numbers

A decade ago TriMet had 2,881 employees. Today, it has 3,435, a 19 percent increase. In 2015 they had 101.7 million boardings. Last year, TriMet had 65.3 million boardings, a 35.8 percent decrease. Transportation system costs were $393 million in 2015; a decade later they were $724 million, an 84 percent increase.

John Charles of the Cascade Policy Institute (CPI) has tracked TriMet for decades. In December he said extending the Yellow MAX Line to Vancouver is TriMet’s worst idea yet. “The transit agency for Vancouver already offers express bus service to Portland, which is a superior ride compared to light rail,” he said. “Spending $3 billion to add rail will be a waste of money. The legislature should cut light rail from the project while it still can.”

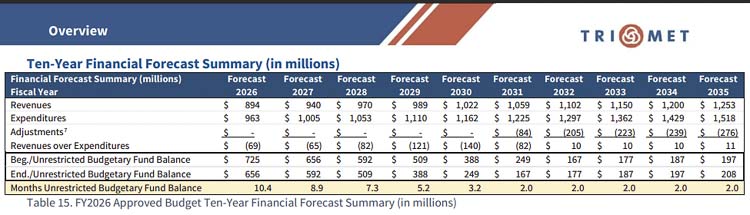

More recently, Charles asked if the agency is even needed. “TriMet anticipates that it will have to eliminate up to 51 of its bus lines by 2031 if it cannot improve its financial condition,” he said. “We should probably let that happen. Transit is important only if people choose to use it. Most people in the metro region are making other choices.”

Taylor Marks of CPI asks, “Is slow, low-ridership light rail really the best usage of lane space on the proposed I-5 bridge? Or, should the new bridge instead expand lane capacity for trucks and cars usage to reduce congestion on the region’s freeways?”

Downsizing TriMet

Four years ago, Charles said the transit agency should pull the plug on their Westside Express (WES) rail service which runs from Beaverton to Wilsonville. “I believe WES is terminal and it should be euthanized,” he told a news reporter. Yes, this was during the pandemic lockdown.

At the time, cost per rider was approaching $108. In March the cost per rider was $93.25 as WES had 479 daily boardings. It served just 269 people per day in 2024. Shutting down WES would save TriMet about $12 million per year in operating and maintenance (O&M) costs.

TriMet officials recently told the Oregon legislature they will eliminate 65 percent of their 78 bus routes by 2031 if they don’t get the huge bailout. With annual bus operating costs of $290 million, that might save about $188 million in 2024 costs.

TriMet officials say they have a $74.4 million deficit for 2026. Pulling the plug on WES, saving $12 million, still leaves needed cuts of about $60 million annually.

In March, TriMet buses averaged 129,435 boardings on weekdays. MAX light rail averaged 65,038 weekdays, half as many people as bus service. Portland separately owns the Streetcar system that is operated and maintained by TriMet. That should also be scrutinized, but financial data on the Streetcar are not part of TriMet’s numbers.

A business minded person would likely look to eliminate routes and services that carry the fewest people, and cost the most. Therefore WES and the Streetcar are candidates for elimination. TriMet bus service is the cheapest and serves twice the number of people, at $7.33 per boarding rider overall.

Presently, passenger fares only cover 8 percent of operating costs, systemwide. Taxpayers pick up the lion’s share of O&M costs at TriMet. That is better than C-TRAN, where passenger fares cover 5 percent of costs. In both cases, passengers should pay a much greater portion of operating costs. TriMet officials told C-TRAN they hope light rail passenger fares will cover 25 percent of costs, up from 8 percent today.

TriMet reports the taxpayer “subsidy per rider” is the least on buses at $6.41; $8.40 on MAX and $98.24 on WES.

Two MAX lines carry the most people – 64 percent of system boardings. The Blue Line carries over 26,000 riders daily and the Red Line over 15,000. The remaining three lines combined (Green, Yellow, and Orange) carry less than the Blue Line. Eliminating those three lines would potentially save TriMet about $72 million, (36% of $200 million operations costs).

Eliminating the three lowest producing MAX lines would have a significant additional benefit. Because roughly two thirds of their light rail vehicles will exceed their useful life in the next decade, that would save taxpayers at least $500 million in capital costs ($5 million per vehicle) in addition to the significant subsidy for transit riders.

With roughly $12 million in savings from closing down WES and $72 million from downsizing MAX, that more than covers the alleged needed TriMet savings. That would free up the Oregon legislature from having to bail out the agency that has lost over $6 billion in the past decade in operations. It also covers TriMet’s $74 million shortfall for the coming year.

Eliminating three MAX routes (Green, Yellow and Orange) plus WES would also allow TriMet to preserve 50 bus routes they say are on the chopping block. As of last year, 22 of their 78 routes carried less than 10 passengers per vehicle hour.

TriMet could pare down non-operational staff as well. Its budget includes $2.7 million for 13 DEI employees; $16 million for 90 Public Affairs employees, and $46 million for 101 IT employees. Then there are 88 Engineering & Construction employees costing $85 million.

National trends

Downsizing TriMet should be on the table because transit ridership is down everywhere in the country. It is not expected to return to pre pandemic levels any time soon. An estimated 35 percent of their passengers are “transit dependent.” The other two thirds have access to private transportation.

According to an American Public Transportation Association (APTA) survey, half of the nation’s public transit agencies are expected to be impacted within the next few years. There is a “doom loop” according to some – a death spiral.

One recent report indicates transit ridership has stalled at 74 percent of pre-pandemic levels as of September 2023. Part of this drop is due to the rise of remote work, a remnant of office closures during the pandemic. MIT researchers found that remote work has “significantly changed urban transportation patterns.”

Most transit services are designed around this suburb-to-downtown model, although most commutes were between suburbs, even before the pandemic. This mismatch may explain the failure of ridership to rebound after the pandemic.

While the Oregon legislature is presently discussing a possible 80 percent increase in the payroll tax to assist TriMet and other transit agencies, they have other significant transportation project challenges needing funding. ODOT revealed a billion dollar error earlier this spring; just one of many problems the agency faces as they ask for more money.

In the meantime, C-TRAN Board members are leary of any financial entanglements with TriMet. Their balance sheet is in better shape overall. With a fiduciary obligation to protect Clark County taxpayers, Camas Councilor Tim Hein asked for a joint meeting with TriMet in June to get a clearer picture of their finances.

Clark County Councilor Michelle Belkot was removed from the C-TRAN Board in March by the County Council. This happened a day after she indicated she would vote to reverse the current C-TRAN policy to “talk” with TriMet about Clark County funding light rail operations as part of the Interstate Bridge Replacement. Two lawsuits have been filed over Belkot’s removal.

Learning more details about TriMet’s finances is vital before a permanent agreement is entered into by C-TRAN or any Clark County agency. Dozens of citizens showed up at their March meeting. The overwhelming majority wanted nothing to do with bringing light rail into Vancouver. They certainly didn’t want to pay more taxes to benefit a transit agency from another state.

Also read:

- Opinion: ‘Southwest Washington residents deserve a better I-5 Bridge replacement project and a more reliable partner to complete it’Ken Vance criticizes Oregon’s failure to pass transportation funding, calling for a more dependable I-5 Bridge replacement plan and a trustworthy partner.

- City of Battle Ground announces speed limit reductions on multiple city streetsBattle Ground will begin installing lower speed limit signs starting June 30 as part of a safety-focused update approved by the City Council.

- Expect delays on I-5 in Clark County for utility work Friday, June 27Drivers on northbound I-5 near 179th Street in Clark County should expect delays Friday due to WSDOT light pole maintenance and lane closures between 7 a.m. and 2 p.m.

- Opinion: You can build your way out of traffic congestionIn a recent column, John Ley responds to IBR Administrator Greg Johnson’s statement that “you cannot build your way out of congestion,” referencing regional and national projects where additional vehicle lanes have improved traffic conditions.

- Opinion: The IBR ‘guessed and guessed low’ on project costsJohn Ley criticizes IBR leadership over rising costs, flawed data, and unverified promises tied to the I-5 Bridge project, calling for serious oversight of the largest public works project in Portland-area history.